Defense Institution Building from Above? Lessons from the Baltic Experience

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 17, Issue 3, p.61-71 (2018)Keywords:

Baltic Battalion, Defense Institution Building, DIB, Georgia, NATO, Partnership for Peace, UkraineAbstract:

Defense institution building seeks to create the means and mechanisms that enable effective capability aggregation within NATO. Can external assistance with DIB help states become suitable NATO members? We discuss the post-Cold War experience of the Baltic States to understand the role of external assistance in defense institution building and how this can enable a state to gain NATO membership. We then consider whether lessons in the Baltic experience are applicable to Georgia and Ukraine.

Introduction

There is nothing better than ‘NATO dirt’ under the ‘fingernails.’ So said then NATO Supreme allied commander in Europe, General John Shalikashvili, in reference to the goal of the Partnership for Peace (PfP).[1] In the aftermath of the Cold War, the states of Eastern Europe looked for aid from the West. The Partnership for Peace (PfP) was NATO’s response. The goal was to bring members of the former Warsaw Pact into closer cooperation with NATO. Participation in the PfP allowed these partner states to reform their defense institutions and policies, both to make their militaries more effective and to align with NATO standards.

More formally, PfP’s goal is Defense Institution Building (DIB). DIB is about creating the means and mechanisms to enable effective capability aggregation within NATO. The ability of the states to combine their military capabilities for the purpose of defending a member state is the foundational principle of all alliances. As Russet and Starr wrote, “throughout history the main reason states have entered into alliances has been the desire for the aggregation of power.”[2] The combined capabilities can then be used to counter—or balance—a threat.[3] Despite the fact that not all of the allies bring the same level of capability contribution to the alliance, NATO is no exception. As Morrow writes, “NATO is an example of an asymmetric balancing alliance.”[4] But aggregation does not happen without allies taking concrete measures to ensure that their militaries can work together, be it on the battlefield or in support roles.[5] Effective capability aggregation is accomplished by enhancing numerous, if not all, dimensions of military interoperability between the allies. These range from ensuring civilian control of member militaries, to developing consistent budgeting practices within defense bureaucracies, to complementary weapons acquisition procedures.[6] These are all forms of DIB.

Efforts at DIB are concentrated in the PfP Planning and Review Process (PARP). Originally open only to PfP countries, PARP was extended in 2011 to other NATO partner countries on a case-by-case basis.[7] NATO carries out DIB through a host of other programs besides PARP: the Professional Development Programme (PDP), which builds the skills of civilian personnel in defense and security institutions; the NATO Defence Education Enhancement Programme (DEEP), which develops a faculty and curriculum of national defense education institutions to meet NATO standards [8]; the NATO Building Integrity (BI) Programme, which combats “poor governance and corruption” in partner countries, and the Defence and Related Security Capacity Building (DCB) Initiative, which provides advising, assisting and training at the request of a partner country.[9]Hence, DIB can ensure compatibility within NATO members and between NATO members and NATO partners.

To understand the role of DIB within NATO’s partner countries, especially those with limited prospects of joining the alliance, perhaps no two countries are more critical than Ukraine and Georgia. Due to relatively recent (the 2008 Russo-Georgian War; the 2014 Russia annexation of Crimea) or ongoing (the presence of Russian forces in Eastern Ukraine) military aggression by Russia, there are no immediate prospects of either state becoming a NATO member. But NATO can and has used the above programs to assist these two countries.

In particular, we think insight into the effectiveness of DIB in Ukraine and Georgia to facilitate NATO membership can be gained by considering the pre-NATO membership experience of the Baltic states. Like Ukraine and Georgia, the Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia are former Soviet Republics. In addition to bordering Russia, all three states were essentially “starting from zero” following independence: “unlike the Warsaw Pact countries, the Baltic states had no military establishment or diplomatic service of their own during the Cold War. These had to be built from scratch in the 1990s.”[10],[11] Hence, any amount of external assistance—in the form of money or technical assistance—would have benefitted the Baltic states. While the Baltics did eventually join NATO, they achieved many defense and interoperability enhancements, primarily in the area of peacekeeping, before taking on Article 5 obligations.

After reviewing the core tenets of the “Baltic Model,” we turn to considering in what respects the experience of Ukraine and Georgia are similar (and different) from that of the Baltics. Finally, we discuss the broader implications of external engagement with the Baltic States, Ukraine, and Georgia.

The Baltic Model

What is the Baltic Model? Building on the work of Poast and Urpelainen,[12] the Baltic model is about the prospective NATO members creating their own, specially tailored organizations and then using those organizations to funnel external financial and technical assistance. This assistance, in turn, fosters the DIB necessary (but not sufficient) to achieve full NATO membership.

As mentioned above, following independence the Baltics were starting from zero. Additionally, the Baltics’ initial situation was fraught with peril due to Russia’s lingering presence. In 1994, then Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt wrote in Foreign Affairs of the “Baltic Litmus Test”: “Russia now borders Western Europe only in the Nordic and Baltic regions. More than any other part of the former Soviet empire, Russia’s policies toward the Baltic countries will be the litmus test of its new direction.” [13] These comments were expressed during a time where then Russian President Boris Yeltsin asserted that “the flames of war” could engulf Europe if NATO expanded.[14] But upon gaining independence, the governments of the Baltic states were unable to provide from their own resources the key public good of security. This meant that immediate NATO membership was effectively closed to the Baltics. Then U.S. President Bill Clinton put the situation bluntly: “We’re trying to promote security and stability in Europe. We don’t want to do anything that increases tensions.” [15]

But while the door to immediate NATO membership was closed, external assistance was on offer. Taking the lead in this effort were the Nordic countries, particularly NATO member Denmark. The Nordic countries and the Baltics agreed that a peacekeeping-oriented international arrangement, the Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT), could serve as a vehicle for quickly bolstering Baltic security. This was for two reasons. First, BALTBAT was, in the words of one commentator with some involvement in the project, of “symbolic and political importance.” [16] By creating and cooperating through BALTBAT, the Baltic states signaled their willingness to find joint solutions to security problems. In other words, they demonstrated a desire and ability to fulfill a core function of NATO: provide collective defense. Second, BALTBAT facilitated the distribution of technical assistance and material resources from the established democracies to the Baltics. With respect to technical assistance, established democracies offered training in “Western” practices of military organization (such as the proper role of civil-military relations), and even English language classes (as English proficiency is necessary for operating within NATO). With respect to material assistance, through BALTBAT the Baltic states received everything from basic military supplies (from uniforms to office equipment) to light weaponry.[17] While far from onerous for the established democracies, these basic resources helped the Baltic states not only strengthen their ties with the West but also improve their military capabilities, professionalize their armies, and learn from the West about civil-military relations in a democratic setting.

How well did the system work for the Baltics? To be clear, the Baltic performance was not perfect. BALTBAT was unable to deploy as a single unit. Following a training and deployment exercise titled BALTIC TRIAL, Danish officials found that Baltic forces were only adequate for performing “routine peacekeeping tasks” in an already peaceful environment.[18] A major problem was a lack of agreement among the three states: they each held strong views on issues ranging from the location of training facilities to the appointment of force commanders. However, this did not prevent each of the individual Baltic states from developing the capacity to deploy forces that demonstrated their usefulness in NATO operations. For instance, Latvian and Lithuanian peacekeepers deployed to Lebanon, and all three states contributed peacekeepers to Bosnia.

The “Baltic Model” shows that external assistance, especially assistance funneled through specially designed international institutions, can offer the technical and material means of enabling non-NATO members to work in tandem with NATO members. If the goal of DIB is to enable effective capability aggregation with NATO (if not within NATO), then the Baltic model demonstrates that this can be accomplished.

Applicability of the Baltic Model to Ukraine and Georgia

How much external assistance is required, and how should it best be channeled, to bring Georgia and Ukraine up to the Baltic level? This section compares and analyzes the pattern of NATO and U.S. military assistance offered to Ukraine and Georgia with that given to the Baltic States. We use U.S. military assistance as a proxy for overall NATO assistance, since data on dollar amounts of U.S. assistance over time by country and program is readily available. We also compare the experiences of the two states, particularly focusing on differences in the efforts of the two states to join NATO. This is important. Despite the Baltic states receiving far less material and financial assistance than Ukraine or Georgia, the Baltics were able to develop their defense institutions to a level acceptable to secure NATO membership, while Georgia and Ukraine are still working to improve their defense institutions. Why the difference in experiences? Georgia and Ukraine are similar to the Baltic States in that both countries are former members of the Soviet Union and share a border with Russia. But unlike the Baltic states, there is not the equivalent of a BALTBAT institution unifying these two Black Sea states and positioning them to contribute to NATO’s mission. Furthermore, NATO membership has been difficult to achieve for Ukraine and Georgia due to political constraints on NATO enlargement, and on the part of Ukraine, previously weak political will to reform defense institutions and pursue NATO membership.

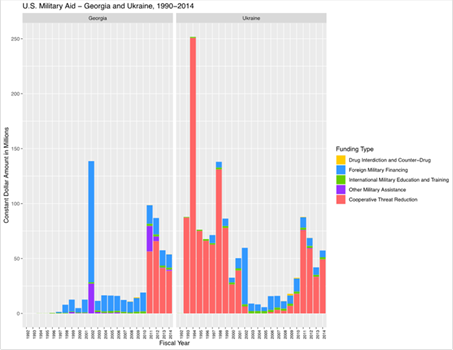

Ukraine received substantial security assistance from the United States between 1992 and 2014. As shown in Figure 1, the majority of U.S. security assistance to Ukraine, nearly $1.1 billion, went toward the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program – removing Ukraine’s strategic nuclear weapons, securing nuclear material, operating laboratories for disease prevention and increasing facility safety, as well as countering smuggling of weapons of mass destruction.[19] While CTR funding filled a critical role in reducing the threat posed by nuclear materials, it did not strengthen defense institutions within Ukraine or build the capacity of its military.

The remainder of the funds to Ukraine, around $222 million, was spent on Foreign Military Financing, International Military Education and Training, and other Military Assistance Programs. But despite this external funding, Ukraine’s military was ill-equipped to oppose the 2014 invasion by Russia. The US and NATO responded by dramatically increasing aid to Ukraine, focusing on enhancing Ukraine’s military capabilities.[20] The United States initiated the European Deterrence Initiative (formerly the European Reassurance Initiative) to provide for

Figure 1: U.S. Military Aid to Georgia and Ukraine, 1990-2014.

joint interoperability and deterrence exercises with NATO and theater partners, as well as specifically earmark security assistance for Ukraine, including lethal and non-lethal equipment needed to fight in Eastern Ukraine. Since 2014, Ukraine has received $850 million in security assistance from the United States.[21] Ukraine has also received varied capacity building assistance from NATO, such as programs to increase its logistics capability as well as efforts at DIB, including the Defence Education Enhancement Programme (DEEP) that started in 2013 to reform the military education system in Ukraine.

The combination of substantial external assistance and the Russian threat to Ukraine’s territorial integrity have provided the impetus for crucial reforms to Ukraine’s military. Ukraine has made significant changes to its military to handle Russian aggression. It increased the defense budget by over 50 percent since 2013 and enacted reforms such as gradually switching from a conscript to volunteer military.[22] As a result, Ukraine will likely emerge from conflict with a military significantly more interoperable with NATO and able to add to the alliance’s capabilities. Furthermore, Ukraine finally shows consistent political will to join NATO, recently becoming an official aspirant country after years of past tepid engagement with NATO. Nevertheless, Ukraine has not fully reached NATO standards. Ukraine’s military at the moment remains underequipped and in need of technical modernization.[23] Ukraine also faces challenges with fully entrenching democratic values in its security sector. While democratic control of the military is legally installed in Ukraine, the presence of volunteer battalions that are not fully under democratic control or whose leadership is involved in politics undermines that norm.[24]

Like Ukraine, Georgia received substantial security assistance from the United States – around $592 million between 1994 and 2014, with around $202 million spent on the CTR and around $390 million on Excess Defense Articles, the Foreign Military Financing Program, International Military Education and Training, Drug Interdiction and Counter−Drug Activities, and Other Military Assistance. Comparatively, Georgia received more money from the United States to procure equipment and modernize its military than Ukraine did, but less money for CTR activities (which reflects the smaller problem that Georgia faced with securing nuclear materials). Georgia also experienced more consistent engagement with NATO than Ukraine, and has been an aspirant country for several years. It has strengthened cooperation with NATO as part of the NATO-Georgia Commission, which was established after the Russo-Georgian War of 2008 prevented Georgia from receiving a MAP to join the alliance. As part of the Commission, Georgia and NATO utilized the Annual National Programme (ANP) and implemented significant reforms to Georgia’s military since the Russo-Georgian War.[25] Georgia has demonstrated its military capabilities by serving as the top non-member contributor and fourth largest overall contributor to the NATO mission in Afghanistan, outperforming the Baltics, Ukraine, and most NATO members. In 2014, NATO created the Substantial NATO-Georgia Package (SNGP), which expands training and exercises between NATO and Georgia, as well as a Defense Institution Building (DIB) school, logistics, and strategic communication.[26]

Given its performance in ISAF, low corruption,[27] and military reforms, Georgia may already meet standards for NATO membership. However, Georgia has not received NATO membership, likely because Russia has become much more opposed to NATO enlargement since the Baltic States joined, particularly for members of the former Soviet Union. Georgia’s ongoing border dispute with the breakaway region of South Ossetia further complicates NATO membership, since aspiring members must resolve border disputes before joining.

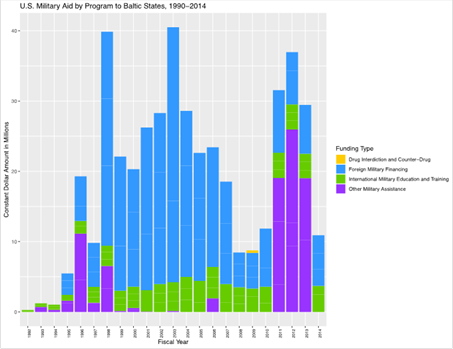

How do the experiences of Georgia and Ukraine compare to that of the Baltics? The amount of assistance to the Baltics paled in comparison to the assistance granted to Ukraine and Georgia. Between 1992-2014, Estonia received around $148 million, Lithuania received around $157 million, and Latvia received around $140 million in security assistance from the United States. Ukraine, in contrast, received over $1.3 billion in security assistance and Georgia received $592 million during the same period. The majority of assistance to the Baltic States went toward Foreign Military Financing (see Figure 2). Like Ukraine, since the 2013 Russian invasion of the Ukraine, the Baltic States have received increased funding from the United States under the European Defense Initiative (EDI). Funds have gone to support a rotational U.S. force to deter Russia from a conventional invasion of the Baltic States, who as members of NATO would require protection under Article 5 in event of a Russian attack.

Given the lower level of overall funding to the Baltic states, the development of institutions necessary for NATO membership appears to have been achieved in a manner not captured by the raw aid figures. How did the Baltic States achieve NATO membership? First, and most importantly, the Baltic States applied for membership much earlier than either Georgia and Ukraine, formally applying in 1994, when the international environment made NATO enlargement to include members of the former Soviet Union more palatable. Second, as discussed in the previous section, the Baltic States demonstrated their capacity for membership through creating and participating in BALTBAT. BALTBAT attracted

Figure 2: U.S. Military Aid by Program to Baltic States, 1990-2014.

significant support from NATO countries, particularly because it showed that the Baltic States were motivated to work toward NATO membership, and to contribute to the alliance’s collective defense. The Baltic States’ participation in BALTBAT furthered regional cooperation, allowed the states to pool resources for arms purchases, and served as a force-multiplier by allowing the Baltics to combine their limited budgets to form a peacekeeping battalion to work closely with NATO, which none of the states could have formed individually.[28] BALTBAT’s peacekeeping duties provided a conduit for working with NATO, which out of the Warsaw (later Wales) Initiative Fund provided unit equipment, communications gear, and support for PfP exercises.[29]

Demonstrating will and capacity for meeting membership standards is also a key criterion for attracting military assistance from NATO member states. For the United States, security assistance is dispensed given the following criteria: “the country must be willing to absorb the engagement, it must ‘buy in’ to the activity by contributing some resources to its implementation, and there must be a reasonable expectation that the country and the region will benefit from the engagement in the long run.” [30] BALTBAT thus furthered the maturation of the Baltic States defense forces and their eligibility for NATO membership more than individual cooperation with NATO or receiving security assistance from member states alone could have.

Conclusions

Despite receiving more funding between 1990 and 2014 than the Baltic States, neither Ukraine nor Georgia are NATO members. Although substantial in overall numbers, external assistance to Ukraine prior to 2014 was oriented towards programs such as the CTR rather than DIB. Ukraine still has work to do in order to fully meet NATO membership standards. In Georgia’s case, its military capability and defense institutions have dramatically improved over the last ten years, but ongoing border disputes and Russian objections make membership difficult. The experience of regional cooperation between the Baltic States through the international organization of BALTBAT—which allowed the Baltic States to gain valuable experience and build their defense institutions prior to joining NATO—points to a way forward for Georgia and Ukraine. Increased bilateral cooperation between Georgia and Ukraine could strengthen their military capabilities, demonstrate their value to the alliance, and serve as a conduit for external military assistance. This middle road of increased partnership between the Black Sea states and with NATO, without immediate prospects of membership, takes into account the geopolitical realities of a resurgent Russia while pursuing opportunities for NATO-assisted security sector reform in Ukraine and Georgia.

From NATO’s experience shepherding the Baltic States to membership and engaging with Ukraine and Georgia, we can draw further conclusions about the future of NATO’s military assistance to its partners. First, the experience of the Baltic States with BALTBAT shows that meaningful reforms can happen, even in the absence of NATO membership, through a combination of external assistance and political will within partner countries. International organizations, when created by countries seeking to improve their interoperability with NATO, provide a means for their member states to gain valuable skills and to take ownership of the reform process. Thus, NATO should encourage and reward with external assistance the formation of international organizations between its partner countries.

Second, the experience of Ukraine and Georgia shows that external assistance alone, without the corresponding political will, does not necessarily bring about reform. However, it also demonstrates that conflict experiences can increase political will to enact widespread and often painful reforms, and encourage existing NATO members to increase their security assistance. While reform in the midst of conflict is often quite difficult, Georgia and Ukraine offer positive examples of how external assistance can build military capacity (particularly by providing critical military equipment) when the aid recipient is highly motivated to improve. This can be true even when a recipient’s defense institutions have historically been weak. Therefore, NATO’s efforts at DIB and its expansion to non-PfP states that have recently participated in conflict, such as Iraq and Jordan, provide a path to meaningful security sector reforms.

About the Authors

Alexandra Chinchilla is a Ph.D. student in Political Science at the University of Chicago. Her research focuses on third party intervention in conflict, proxy warfare, security cooperation, NATO, and alliance politics. She received a Bachelor of Science from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, and has interned at the RAND Corporation, the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw, and the House Armed Services Committee.

Paul Poast is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago, where he is also a research affiliate of the Pearson Institute for the Study of Global Conflicts and a member of the Center for International Social Science Research advisory board. He studies international relations, with a focus on international security.

E-mail: paulpoast@uchicago.edu.

[1] Paul Poast and Johannes Urpelainen, Organizing Democracy: How International Organizations Assist New Democracies (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 147.

[2] Bruce Russett and Harvey Starr, World Politics: The Menu for Choice, 3rd ed. (New York: W.H. Freeman, 1989), 91.

[3] Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliance (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987).

[4] James D. Morrow, “Alliances and Asymmetry: An Alternative to the Capability Aggregation Model of Alliances,” American Journal of Political Science 35, no. 4 (November 1991): 904-933, 928

[5] Nona Bensahel, “International Alliances and Military Effectiveness: Fighting Alongside Allies and Partners,” in Creating Military Power: The Sources of Military Effectiveness, ed. Risa Brooks and Elizabeth Stanley (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), 186-206, 188.

[6] NATO, “Defence Institution Building,” May 2018, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50083.htm.

[7] NATO, “Partnership for Peace Planning and Review Process (PARP),” November 2014, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_68277.htm.

[8] NATO, “Defence Education Enhancement Programme (DEEP),” December 2017, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_139182.htm.

[9] NATO, “Building Integrity,” September 18, 2017, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_68368.htm.

[10] Andres Kasekamp and Viljar Veebel, “Overcoming Doubts: The Baltic States and European Security and Defence Policy,” in The Estonian Foreign Policy Yearbook 2007, ed. Andres Kasekamp (Tallin: Estonian Foreign Policy Institute, 2007), 9-33, 13.

[11] Quoted in Pete Ito, “Baltic Military Cooperative Projects: A Record of Success,” in Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States, ed. Tony Lawrence and Tomas Jermalavičius (Tallin: International Centre for Defence Studies, 2013), 242, https://icds.ee/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/RKK_ Apprenticeship__Partnership__Membership_WWW.pdf.

[12] Poast and Urpelainen, Organizing Democracy.

[13] Carl Bildt, “The Baltic Litmus Test: Revealing Russia’s True Colors,” Foreign Affairs 73, no. 5 (1994): 72-85, 72.

[14] Quoted in Brendan Simms, Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, from 1453 to the Present (Hachette, UK: Basic Books, 2013), 496.

[15] Poast and Urpelainen, Organizing Democracy, 133.

[16] Ito, “Baltic Military Cooperative Projects,” 252.

[17] Poast and Urpelainen, Organizing Democracy, 144.

[18] Poast and Urpelainen, Organizing Democracy, 145.

[19] “Fiscal Year 2017 President’s Budget Cooperative Threat Reduction Program,” Defense Threat Reduction Agency, 2017, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2017/budget_justification/pdfs/01_Operation_and_Maintenance/O_M....

[20] Adriana Lins de Albuquerque and Jakob Hedenskog, “Ukraine: A Defense Sector Reform Assessment” (Stockholm: FOI, December 2015).

[21] “The European Deterrence Initiative: A Budgetary Overview,” Congressional Research Service, August 8, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/IF10946.pdf.

[22] Denys Kiryukhin, “The Ukrainian Military: From Degradation to Renewal” (Foreign Policy Research Institute, August 17, 2018), https://www.fpri.org/article/2018/08/the-ukrainian-military-from-degradation-to-renewal/.

[23] Andrzej Wilk, “The Best Army Ukraine Has Ever Had: Changes in Ukraine’s Armed Forces since the Russian Aggression” (OSW, Centre for Eastern Studies, July 2017).

[24] Albuquerque and Hedenskog, “Ukraine: A Defense Sector Reform Assessment.”

[25] Embassy of Georgia, “Georgia-NATO Relations,” 2017.

[26] F Stephen Larrabee, “The Baltic States and NATO Membership,” n.d., 11.

[27] “Georgia Corruption Rank,” Trading Economics, 2018, https://tradingeconomics.com/georgia/corruption-rank.

[28] F Stephen Larrabee, “The Baltic States and NATO Membership,” RAND, 2003.

[29] U. S. Government Accountability Office, “NATO: U.S. Assistance to the Partnership for Peace,” no. GAO-01-734 (July 20, 2001), https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-01-734.

[30] Walter L. Perry, Stuart Johnson, Stephanie Pezard, Gillian S. Oak, David Stebbins, and Chaoling Feng, Defense Institution Building: An Assessment (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016). https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1176.html.

- 15784 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML