Lessons Learned from Military Intelligence Services Reform in Hungary

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 20, Issue 1, p.33-49 (2021)Keywords:

external intelligence, Hungarian Defence Forces, Hungary, intelligence, internal intelligence or counterintelligence, lessons learned, military, military intelligence reform, national security services, political situationAbstract:

The classic types of national security services are external and internal intelligence services, as well as integrated, internal, and external intelligence organizations. From a professional perspective, external and internal intelligence cannot be interpreted as entirely independent. Some theoretical schools consider internal intelligence (counterintelligence) part of intelligence; others attribute a significant distinction between internal and external intelligence. Regarding the number of national security services, two trends are observed in countries comparable to Hungary in the last decade. One is the increase in the number of services reflecting the increasing number and complexity of tasks and threats; the other is the decrease in the number of services through the integration of existing organizations, usually due to financial reasons.

In Hungary, military internal and external intelligence were merged in 2012, establishing an integrated organization, the Military National Security Service (MNSS). Although an impact assessment did not precede the merger, the official evaluation of the Court of Auditors in January 2014 stated that the creation of NMSS resulted in savings in public money and this new organizational form ensured the better implementation of unchanged tasks.

This article briefly presents the current political situation in Hungary, the Hungarian secret services, the development of the Hungarian Defence Forces in the past decade, the reasons for reforming the special military services, the periods, the aims, and the results of the integration process. It provides general and specific conclusions and lessons learned from military intelligence services reform in Hungary.

Introduction

National Security Services

Generally, we distinguish between two types of national security services. One is the internal intelligence service (or counterintelligence), which collects and manages information about a country’s internal security. Its task is to protect the state, the territory, and society from foreign interference (subversion, espionage, political violence). The information collected by this service contributes to upholding and guaranteeing the internal security of the state and society. The other is the external intelligence service, aiming to learn about the probability and consequences of events of foreign origin that pose a threat to the country. Therefore, such services collect information relating to foreign governments, organizations, non-governmental formations, foreign state intelligence services, or agents that pose an actual or potential threat to the country and its foreign interests. Information gathered by external intelligence services serves the enforcement of national interests, including political, economic, military, scientific, and social interests.

The tasks and objectives of these two types of information-gathering services are therefore different. The nature and extent of the threats they address also vary. The management, control, and supervision systems of these services must reflect these differences. Because a state’s internal intelligence service (counterintelligence) collects information about its own citizens, mostly within the country, its activities require strict control. This is necessary so that the interests of deterrence do not prevail unrestrictedly against the rights of individual citizens and legal entities.

Intelligence or information gathering organizations (internal and external intelligence) usually perform three main tasks: information gathering, analysis, and internal protection of these activities (protection against phenomena that endanger their own activities).

Secret actions are also a controversial but undoubtedly necessary element of the activities of the intelligence services of modern democracies. The CIA defines covert actions as operations that affect the activities of governments, events, organizations, and individuals in the conduct of foreign policy in a manner that does not disclose the customer of those operations.[1] The boundaries between the activities of external and internal intelligence services have never been strictly separable. Both types see the fight against terrorism, organized crime, drug trafficking, and smuggling as their own task, both internally and externally. As the DCAF Intelligence Working Group elaborates:

The establishment of a centralized service may be a justified need, as the security of a country can only be achieved through close cooperation between internal and external intelligence services. If, for example, an extremist group plans an armed attack on the country and gathers information to carry it out, it is up to internal intelligence to detect the act. If the said group receives support from a neighboring state in the form of assisting in the immediate preparation of the attack and in training the participants in the territory of the neighboring state, it is already the responsibility of external intelligence to detect this. In this situation, only a centralized integrated organization that coordinates the activities of the external and internal intelligence services can respond effectively to the threat.[2]

According to a rigid and now outdated sectoral model supported by only a few countries, intelligence is only one of the foreign branches of national security activity. According to the modern conception, however, intelligence is a basic activity, the main task and method of all national security—i.e., ‘secret’—services, which Hungarian law calls “secret information gathering.” It means that internal and external intelligence conduct a common activity, namely information gathering. It is not the foreign or domestic orientation that distinguishes the internal and external intelligence services, but the area of operation (foreign or domestic) and the operational, technical, and organizational aspects. Strict enforcement of operational security and conspiracy requirements, for example, is just as important at home as it is abroad but can be achieved under different conditions and in part by different methods.

National Security Services of Hungary

Hungary 2020 – Political Situation

The temporary collapse of the hegemony of neoliberalism in some Central European countries after 2008 led to a wave of populism in these countries. Populist parties and movements include both left- and right-wing actors. One of their few common characteristics is that they all criticize the ruling elite and its ideology, claiming that elites oppress the people and the nation. According to the left-wing rhetoric, the social and economic policy of Orbán’s populist government is strengthening the nation’s capitalist class, selling out cheap workforce to foreign industrial investors while disciplining the workers, and performing centralized control of the poor living primarily in rural areas. The purpose of its cultural policy is to promote the official Hungarian ideology of the era before 1938 – a conservative, Christian, nationalist ideology, with historical lies, an unjust social system, hostile atmosphere, and the (yet hidden) intention to recover territories lost after World War I. Orbán perceives the neoliberal European Union, the international capitalists’ secret fraudulent practices represented by George Soros, and migrants as enemies in order to declare his political opponents as the enemy of the nation and take the role of its rescuer. While the government is attacking some of the EU values in political fora and is confronted loudly, it is a subordinated ally of European capitalists in terms of economic processes.[3]

Due to Viktor Orbán’s new nationalist regime-building politics, democracy, the rule of law, and pluralism in Hungary have become limited and resulted in the establishment of a country with illiberal democracy. In Hungary, those in power suggest that leftists and liberals are not part of the nation, and anything that is left or liberal, be it the person, any artwork, or just a point of view or an approach, should be deemed as alien and rejected since it goes against the official national Christian conservative course.

Orbán’s political views are faithfully reflected in his speech on August 20, 2020, at the inauguration ceremony of the Monument of National Cohesion commemorating the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty. Prime Minister Orbán said in this speech that “Western Europe, weakened by embracing the ideas of a Godless cosmos, rainbow families, migration and open societies is losing its leading position in the world and is becoming less and less attractive for Central Europeans.” He called on Central European countries that want to maintain their Christian heritage to create a strong coalition that can help reorganize Europe. Orbán added that the main lesson of the past century is that nations need to fight and show their strength to maintain their sovereignty and freedom. Orbán formulated the seven tenets of Hungary’s nation-minded policies in the 21st century: the homeland exists only as long as there is someone there to love it; every Hungarian child is a new ‘lookout’; truth is worth little without power; Hungarians will only get to keep what they can defend; “every match lasts until we win”; it is the country, not the nation that has borders and that no Hungarian is alone.[4] Accordingly, Hungary makes significant investments in developing its defense forces and modernizing its national security services.

Hungary’s National Security Services – A Brief Historical Overview

Upon breaking away from the Soviet-led regime, five national security services were created in Hungary: the National Security Office (NSO, civilian counterintelligence service); the Information Office (IO, the civilian external intelligence service); the Military Security Office (MSO, the military counterintelligence); the Military Intelligence Office (MIO, external military intelligence).; and the Special Service for National Security (SSNS), responsible for providing special tools and methods of secret information gathering for other security services as customers (e.g., wiretapping). SSNS was separated from the rest of the agencies to allow for an equal distribution of power among them.

A minister without a portfolio oversaw the civilian national security services (NSO, IO, and SSNS), while the military intelligence services were subordinated to the Minister of Defense. In the meantime, the National Security Office was renamed, the new name being Constitutional Protection Office (CPO). Further, the Counter-terrorism Center (CTC), subordinated to the Ministry of Interior, was established in 2010 by bringing together the terrorism-related information gathering and the operational response to acts of terrorism. An organization with such a combination of responsibilities is unique in Europe. A new organization of the Ministry of Interior was created to combat corruption within the law enforcement agencies, including national security services, by reorganizing the previous agency with such responsibilities, the Protective Service of Law Enforcement Agencies (PSLEA). The powers of PSLEA have subsequently been extended, and its name was changed to National Protective Service (NPS). The parliamentary control of those services has been and will be carried out by the Committee of Defense and Law Enforcement and the National Security Committee.

Taking advantage of the two-thirds majority in the Parliament, Orbán’s government introduced major changes in the country’s national security system during his second and third terms. Shortly after Orbán’s government took office for the second time, the provision of the National Security Act to prevent the Minister responsible for law enforcement from controlling civilian national security services was abolished. This change terminated the public agreement and openly reverted to earlier times when the Ministry of Interior had been the primary protector of the regime. The Constitutional Protection Office and the Special Service for National Security were placed under the supervision of the Minister of Interior. The authorization of police units to carry out covert intelligence-gathering was extended. The position of the Minister without portfolio in charge of the civilian intelligence services was abolished, thus disrupting the unified government control of the civilian services. The Information Office was finally placed under the authority of the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Surprisingly, the Minister of Interior was appointed to lead the Government task force handling the Ukrainian crisis. The professional expertise of the task force was questioned when, in the last wave of staff cuts, several experts with outstanding capabilities, who had graduated in the former Soviet Union, spoke the target languages, and had possessed knowledge of Russian-Ukrainian culture, were removed from the Military National Security Service (MNSS). In the wake of the refugee crisis in 2015, the Parliament transferred the authority to declare a refugee-related state of emergency from the President of the Republic to the Government (Minister of Interior). The military troops involved in the protection of borders were placed under the authority of the Police.

Upon amendment of the National Security Act, the Counterterrorism Information and Criminal Analysis Center (CTICAC) was established under the supervision of the Ministry of Interior and received special national security functions (integrated analysis and assessment, coordination, tasks assignment, performance evaluation). An agency with these functions would require centralized, governmental, and not ministerial supervision. Thus, in 2018, to offset the increasing power of the Minister of Interior, the oversight of CTICAC was transferred to the State Secretariat for National Security, established within the Prime Minister’s Office. CTICAC as an “intelligence center” should have been established by amending the Act CXXV of 1995 (National Security Act), not under separate legislation. At the same time, it would have been more appropriate to set up an integrated analysis-assessment, coordination, task assignment, and performance evaluation organization under the supervision of the Prime Minister (for example, through an Information Analysis and Assessment Center for National Security), and to place the Counterterrorism Information and Criminal Analysis Center under the responsibility of the Minister of the Interior, possibly the Head of the National Police, but with limited authority and detailed legal definition of cooperation obligations.

The National Security Authority, established on the basis of Hungary’s NATO membership to enforce the requirements of the Alliance’s security regulations, was integrated into the organization of the Ministry of Interior in the new government cycle starting in 2014 as a department-level organization. With this, the Ministry of Interior has gained an overview of the confidentiality aspects of international information exchange conducted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior while excluding itself from the independent oversight of confidentiality. At the turn of 2011 and 2012, the government achieved its old objective by merging the two military national security services, namely the Military Intelligence Office and the Military Security Office.

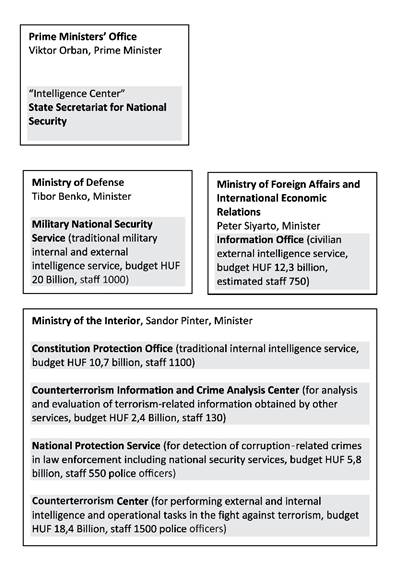

Figure 1 shows Hungary’s national security services operating in 2020 and the characteristics of the services.

Integration of the Military Intelligence Services

Development of the Hungarian Defense Forces

Hungarian Defense Forces (HDF) is the official name of the Hungarian Armed Forces. Since 2007, the armed forces are under a unified command structure. The Ministry of Defense maintains political and civil control over the army. A subordinate Joint Forces Command is coordinating and commanding the HDF units. The Hungarian Defence Forces had 28,000 personnel on active duty. In 2019, military spending was $ 1.904 billion, or approximately 1.2 % of the country’s GDP, well below the NATO target of 2 %. Military service is voluntary, though conscription may occur in wartime. According to the Hungarian Constitution, the three pillars of the nation’s security are the strength of the HDF, the Alliance system, and the citizens.

Figure 1: National Security Services of Hungary.

The Hungarian government aims to make the military one of the “most decisive” armies in the region. An increased budget will be available for a larger force, and the defense budget will reach 2 percent of GDP, or 1 trillion HUF, by 2024. The defense and armed forces development scheme, named Zrínyi 2026, and the increased budget will enable the acquisition of state-of-the-art technologies to ensure that the army maintains 21st-century capabilities.

The potential of the national economy ensured opportunities to develop the armed forces, unprecedented for the past 25 years. The MoD elaborated medium- and long-term strategies to enable the army to respond appropriately to both present and future challenges. Under the Zrínyi 2026 program, the government will change soldiers’ personal equipment such as clothing and weapons and modernize the Army and the Air Force.

Hungary’s defense forces plan to buy 40 new helicopters in the coming years (twelve Russian-made Mi-24 helicopters are currently under comprehensive modernization in Russia and will be in service until 2025). The Hungarian Defense Forces have already purchased two transport planes, which will be in service in 2020. They can carry military personnel and their individual equipment, as well as smaller supplies. They will also be equipped with capabilities to carry out air rescue missions. Hungary needs larger aircraft as well, capable of carrying large military supplies and equipment and fitted with aerial refueling capability.

As part of its commitment to NATO, Hungary is replacing its heavy ground forces equipment. Following the tanks and artillery, it is now the turn of the infantry fighting vehicles, which form the backbone of the capabilities set. One of Europe’s foremost maker of army equipment will cooperate with Hungary to create a joint venture and production facility in Hungary to manufacture the most modern infantry fighting vehicle.

The military contributed some 15,000 soldiers to Hungary’s border control efforts in the last years. At the same time, the Hungarian armed forces participated in some 40 international exercises, while some 1,000 troops served in international missions. Hungary’s voluntary reserve force of 5,300 is under development into a national network with units in each district of the country. The government greatly appreciated the work of soldiers, and their salaries have been raised by more than 40 percent since 2015.

The HDF development priorities are establishing a supportive and involved population and a voluntary reserve force, adequate military strength (replacing air force and heavy ground forces equipment), improved resilience to hybrid and cyber threats, and effective internal and external intelligence. To make military internal and external intelligence more effective, in 2011, the parliament decided to merge the two military intelligence services.

Before describing the integration process and its consequences and effects, I will present the military secret services merged one by one.

History of the Military Security Office

At the time of the change of social system, the organization, personnel, and working methods of the III/ IV Directorate of the Ministry of the Interior (the military internal intelligence directorate) were essentially transferred to the successor organization, the Military Security Office (MSO). At the time, the country’s political and economic leadership needed the expertise of experienced, trained military internal intelligence personnel.

The “regime change” of 1989-90 did not affect the MSO markedly. The organization’s notion of “the enemy” remained essentially unchanged: it continued to focus on examining the reliability of our own external intelligence officers and detecting the military intelligence activities of all foreign countries.

The Military Security Office lived its heyday under the leadership of Géza Stefán, who became Director-General in 1994 and held this position for 15 years – an unprecedented achievement in the history of the Hungarian public administration.

After retiring with the rank of a four-star general, he continued to run the office as a “civilian employee,” and with each change of government managed to gain and maintain the trust and satisfaction of both leading parties, the Socialist Party and the Young Democrats (Fidesz).

Furthermore, as an excellent national security expert who graduated in the Soviet Union and was familiar with the Russians, he enjoyed the goodwill of the new Western Allies and Moscow simultaneously. Thus, he formed a kind of a bridge between former Cold War opponents, bringing together Russian and Allied secret services in the fight against global threats such as proliferation, terrorism, the illegal arms trade, and organized crime.

However, according to a widespread view in the secret service circles, the real explanation for his performance was that he carefully kept the personnel files of former informants obtained in his previous position in the Directorate of Internal Security of the Ministry of the Interior, which proves that a significant part of the ‘new’ Hungarian political and economic elite cooperated secretly with that Directorate. Although there is no evidence to support this view, it is in any case strange that the Hungarian Parliament has not yet adopted a so-called “agents law” on disclosing the names of former state security agents.

There have also been lows in the history of the Military Security Office, such as the involvement in mafia crimes related to oil imports and serial killings of ethnic Roma citizens, and the attempt to ‘occupy’ the Military Intelligence Office around the turn of the century, when, with the support of the government, a deputy director-general was transferred temporarily from the Military Security Office to the Military Intelligence Office. The attempt then failed but was repeated by the second Fidesz government with complete success by merging the two military services in 2011-2012.[5]

The organizational structure of the Military Security Office in 2011, before integration, was as follows: the Legal and Audit Department, the Department of Internal Security, the Human Resources Department, the Education Department, the National Security Office (with publically unknown purpose), and the Data Repository were directly subordinated to the Director-General. The Administrative Directorate, the Operations Directorate, the Evaluation, Analysis and Information Directorate, and the Personnel and Industrial Safety Directorate were under the authority of the Deputy Director-General, reporting directly to the Director-General.

History of the Military Intelligence Office

The legal predecessor of the Military Intelligence Office, the Second (Foreign Intelligence) Directorate of the General Staff of the Hungarian People’s Army, occupied a very prominent place among the military intelligence services of the member states of the former Warsaw Pact. This is due to the so-called Conrad case.[6] Conrad was the head of the confidential documents’ handling office of the 8th US Infantry Division stationed in Germany and the star agent of a spy network named after him. He was recruited by Hungarian foreign military intelligence in 1975 by another American soldier, Zoltan Szabo of Hungarian descent, a Vietnam veteran. Szabo was successfully involved in the work of the 2nd Directorate of the General Staff of the Hungarian People’s Army in 1971.

Szabo served in Bad Kreuznach, from where he knew Conrad, and they both recognized the opportunity offered to them by the security deficiencies of the 8th Division’s confidential documents handling office. Conrad smuggled (and then smuggled back) and copied top-secret documents from the confidential documents handling office on a large-scale, and sent the copies (or sometimes the ‘discarded’ originals) to Hungarian foreign military intelligence through the Kercsik brothers. The Kercsik brothers were doctors living in Sweden. They traveled a lot in Europe and transported the ‘material’ to Vienna in their medical bags, which they passed in secret meetings to an officer of the 2nd Directorate of the General Staff.

For almost twenty years, the Conrad Group provided invaluable information to Hungarian—and through it, Soviet—military intelligence, immensely threatening the security of the United States, Germany, and NATO as a whole. The documents handed over included original NATO military-operational (defense) plans, detailed organizational, armaments, combat readiness data, the nuclear force alert system, and the location of the nuclear mines. With this information, the Soviets could have occupied the whole of Western Europe in a short time by launching an unexpected attack, and the United States could have avoided that only if ready to escalate to a global nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

In the period of social changes, Hungary needed US goodwill, and the outbreak of the Conrad affair came at the worst possible time in the 1980s. Professionally, this was the greatest success in the history of Hungarian military intelligence, but politically it was the most severe and unpleasant heritage of the Kádár regime. As a result, the government had to apologize publicly and express regrets that, by handing over intelligence information to the Soviet Union, Hungary threatened the security of the United States and Western Europe.

After the regime change, the staff reductions affecting the Hungarian Defence Forces over the years naturally affected the legal successor of the 2nd Directorate of the General Staff and, consequently, the Military Intelligence Office. By the summer of 2007, the initial staff of 1963 melted down to 733. At that time, at the initiative of the Director-General of the Military Intelligence Office, the Minister of Defense ordered a full review of its operation in order to meet growing international obligations and enhance information gathering and reporting. Following the screening, in 2008, the following directorates and other organizational elements were established under the authority of the Director-General of the Military Intelligence Office: HUMINT (Human Intelligence) Directorate; SIGINT (Signal Intelligence) Directorate; Directorate for Information Analysis, Evaluation, and Reporting; Human Resources Directorate; Security and Administration Directorate; Directorate for Logistics, Development, and Finance; Planning and Coordination Department; the National Security Secretariat (with unknown purpose); Attachés’ offices. The Military Intelligence Office operated military attaché offices in 19 countries, and our military diplomats were accredited to a total of 56 countries. This figure has changed and continues to change due to evolving military relations, the security situation, and budgetary considerations. Attaché offices are managed and supervised by the Minister of Defense through the Deputy State Secretary for Defence Policy of the Ministry of Defense and the Director-General of the Military Intelligence Office (currently Military National Security Service). Multiple accreditations (a defense attaché representing the Ministry of Defense of Hungary in one foreign country is also accredited to other countries) and the regional military attachés (stationed in Budapest and regularly visiting the countries where they are accredited) allow to perform military diplomacy tasks cost-effectively.

The Merger of Military Intelligence Agencies

According to the political leaders, by 2011, a single organization has become necessary to properly manage military intelligence and counterintelligence activities, allowing more prudent use of budgets. (In the longer term, the expected savings resulting from the reduction of properties used by the two predecessor organizations alone will amount to several hundreds of millions of forints.) The integration was done in two stages. The first phase was carried out between August and November 2011 with the following objectives: to create conditions for speedier information flow; to facilitate more efficient use of resources; to eliminate duplication of efforts to enhance the effectiveness of operations; to increase the efficiency of protecting Hungarian troops deployed in operations; to operate fewer properties and thus reduce expenditures. The period between January 1 and April 30, 2012, can be designated as the second phase of integration, characterized by the following tasks to establish a new organizational model: development of unified management of military intelligence and counterintelligence activities; optimization of management levels and senior positions; revision of internal rules and the operational instruction system; review of cooperation agreements, implementation of logistic, personnel-related, and technical integration.[7] A new Organizational and Operational Policy was developed under the statutory requirement. It detailed the functions of the Military National Security Service (MNSS) and the basic rules governing its organization, management, and operation under the relevant legislation.

In terms of Parliamentary oversight, democratic control has been exercised by the Parliament’s Committee of Defense and Law Enforcement and the National Security Committee.

Expansion of the MNSS Functions

The amended National Security Act added a new responsibility to the scope of MNSS national security activities. Previously, this task was not included among the responsibilities of any of the predecessor organizations. MNSS’s new responsibility entails the collection of information about cyber activities compromising defense interests. The primary task of the new organizational unit responsible for the above function is to address the challenges faced by the IT systems and thwart cyberattacks attempting to compromise defense- and national security interests.[8] To comply with the statutory requirements, a Cyberdefense Center was founded on March 1, 2016. With its three departments, it is able to perform all activities related to incident management, the exercise of authority, and vulnerability assessment and analysis.[9]

The Reconnaissance Department within MNSS, founded on June 1, 2014, took over the responsibilities of the General Staff of the Armed Forces’ Reconnaissance Department disbanded on this date. With this organizational transformation, the tactical reconnaissance capabilities of the Hungarian Defense Forces (HDF) and strategic intelligence capabilities of the Ministry of Defense were placed under single professional management, and the Director-General of the MNSS exercises professional control over the HDF reconnaissance capabilities. This solution allowed for centralized management and decentralized execution of tactical and strategic level reconnaissance and intelligence activities.

New opportunities emerged for electronic specialization within the HDF, which opened up opportunities to form and develop new intelligence branches (e.g., IMINT capabilities, ground moving target detection capabilities).

The current structure of the Military National Security Service is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Structure of the Military National Security Service.

Findings, Conclusions, and Lessons Learned

In its January 2014 report on the merger of the two military intelligence agencies, the State Audit Office (SAO) states: “Generally, it can be established that founding MNSS resulted in savings of public resources and, at the same time, considering that the basic tasks remained unchanged while the staff was reduced, a more efficient organizational structure was established, creating the circumstances necessary to encourage further development in terms of professional activities.” One of the issues regarding this report is that the adoption of findings concerning the execution of professional, specialized tasks falls outside SAO’s competence since it lacks the necessary expertise. Another issue is that the budget calculations contradict each other. According to the SAO report, the aggregate expenditures effected for and by the Military Security Office and the Military Intelligence Office prior to the 2011 merger amounted to HUF 12,019.5 million, while the annual expenditures for and by MNSS in 2012 stopped at HUF 11,327.0 M. In other words, by the end of the 2012 financial year (MNSS’s first year), the operation of the new organization resulted in savings of HUF 692.5M, which was mainly attributed to the staff reduction.[10]

Table 1. Yearly Budget of the Military Security Office (MSO), the Military Intelligence Office (MIO), and the Military National Security Service (MNSS) in the Period of 2010-2018.[11]

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

MSO | 2,5 | 2,6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MIO | 9,2 | 9,4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total | 11,7 | 12,0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MNSS |

|

| 11,3 | 10,9 | 10,4 | 14,9 | 18,5 | 34,6 | 28,2 |

As the credibility of the SAO report ought not to be questioned, my observations are limited to a few remarks: Previously, the Military Intelligence Office employed 733 people, while Military Security Office’s headcount was 225. Just before the merger, the former organization’s staff was cut by 155 (21.15 %), and that of the latter by 62 people (27.56 %). The original organizations carried out the personnel reductions, and the substantial expenditures involved did not affect the 2012 MNSS budget. Financial experts argue that staff reductions in operation support and logistics result in annual savings of HUF 1.55 billion. Taking this into consideration, the 2012 budget savings seem quite modest. This is even more awkward if we also consider the attaché offices’ budgets. According to the SAO report, if the aggregate costs of approximately twenty attaché offices are the equivalent of 100 units in 2010, these costs amounted to 120.2 units in 2011 and 85 units in 2012, which should have also resulted in significant savings.

The finding contending that the creation of MNSS resulted in the saving of public assets is definitely true; however, in MNSS’ first year, these savings did not meet the expectations.

Several Hungarian studies [12] discuss the assessment of MNSS’ operation, and these studies consistently and firmly state that the merger was successful and has improved the standards of intelligence and counterintelligence activities. Without questioning the conclusions of said studies, I would offer a few facts here. First, the number of MNSS’ initial personnel should have been equal to the total number of staff employed by the Military Intelligence Office (578) and the Military Security Office (163) right after the staff cut (741) while, based on a Minister of Defense decision, MNSS received more positions and started its operation with 825 personnel. It is not known when this ministerial decision was made – before the start of the staff reduction or after its end. If the decision was made after the staff reduction, the dismissal of 84 officers was unnecessary. Second, the most important positions in terms of execution of the merger (the management of the department coordinating domestic and foreign operations, the senior positions of the personnel and training department, responsible for the practical execution of the merger, as well as the management of the Internal Security Directorate) went to officers from the Military Security Office. As a consequence, young, highly qualified, and language-savvy intelligence officers, NCOs, and civilian colleagues became redundant on fabricated reasons or security concerns. In contrast, many older, relatively unqualified intelligence officers who did not speak any language were brought in. Third, the majority of the upper management positions of the Military National Security Service were occupied by officers of the National Security Office, even though based on the pertinent legislation and the ministerial instructions, the Military Security Office was the organization to be disbanded and merged into the Military Intelligence Office when the latter organization only changed in its name (Military National Security Service). The predominance of military counterintelligence and its values might facilitate the emergence of ungrounded caution and permanent suspicions in intelligence activities, adversely affecting the efficiency of foreign intelligence.

Based on the above, including the radical cut of the attaché office budgets, I am positive that in the first year of the merger, MNSS’s foreign intelligence opportunities significantly narrowed down, but without compromising the performance of the basic task (continuous gathering of information in specific directions).

The most important conclusions and lessons learned from the reform of the Hungarian military intelligence services are the following:

1. As the internal intelligence (counterintelligence) service of a state gathers information domestically about Hungarian citizens, their activities require close control. In Hungary, in the case of the Military Security Office, this control was not efficient. Therefore, upon merging the two military intelligence agencies, counterintelligence had a better starting position and acquired a larger influence in the integrated organization than is its actual significance. This circumstance might affect the effectiveness of foreign intelligence for the years to come.

2. The integration of the two military intelligence agencies was not preceded by a thorough impact study supported by research. Staff reduction was executed like in the disciplined military, but the personnel requirements of the allocated tasks had not even been assessed. So, managers implementing the integration continuously faced the financial, human resources management, and professional integration challenges of mergers and reorganizations. They were eager to find the best solutions to the anomalies, yet this could not compensate for the inadequate reform preparation. This should serve as an example to be avoided by any country.

3. When merging two government offices, it is essential to respect professional considerations and political neutrality fully. These principles should also be respected in the appointment of members of the top leadership of the new organization. Unfortunately, this was not the case when the Hungarian military secret services were merged. The post of Deputy Director-General of the merged organization was given to the former “intelligence adviser” of the ruling party (Young Democrats – Fides), a patron of the speaker of Parliament, without a military degree and knowledge of any foreign language. His nearly one and a half year of activity has done a lot of harm to the new organization. The circumstances of his replacement are still obscure. According to the press, he wiretapped his superior, the Minister of Defense, and therefore had to resign. Further, a widespread view in the secret service circles claimed that he wanted to get the MNSS Director-General position without coordinating his actions with all the key figures in Fides.

4. The most used justification for all mergers is eliminating duplication of efforts between the organizations to be merged. In the case of military intelligence agencies (military counterintelligence and intelligence), this duplication may be present, but not to the extent where this could not be solved by the amendment of the respective organizations’ operational and organizational policies.

5. If a counterintelligence officer sees a top-secret document left on the table, he/she will want to know who left it on the table. If an intelligence officer sees the same document, he/she will be interested in its content. The two functions require two different approaches and methodologies, not to mention the differences in the personality traits necessary for their performance. If both the intelligence and the counterintelligence officer perform their own task, it will most likely be clear to both who left the secret document on the table and also what the document contains. Official mutual information exchange can confirm the authenticity of the information obtained by the agencies independently from each other. The merging of military intelligence and counterintelligence is therefore not absolutely necessary. Still, the need for more effective action against new types of threats (e.g., hybrid warfare, information operations) may justify the merger.

Closing Remarks

The history of the Military National Security Service dates back to the time between the two world wars. The current integrated foreign (external) and domestic (internal) intelligence organization was established in 2012 by merging the Military Intelligence Office and the Military Security Office of the Republic of Hungary. Despite many shortcomings in its preparation and implementation and the lessons learned, the merger was a success. The organization currently has a wide range of responsibilities: a collection of military information in foreign countries (including by secret means and methods) on which government decisions are based, detection of foreign military secret services’ activities in Hungary and protection of Hungarian military units against them, protection of personnel involved in crisis response operations abroad, implementation of national security and lifestyle checks of Service’s personnel, gathering information on terrorism and organized crime, cyber defense, and scientific activities. Civilian control of the Service is exercised through the Military and Law Enforcement Committee and the National Security Committee of the Hungarian Parliament. This parliamentary control is extremely important. Without full publicity, it is not possible to assure the citizens that the operation of the Service is not detrimental to their interests or that it is efficient from a budgetary point of view. However, it is not felt that the organization has an appropriate communication strategy to deal with the public. Although the instructions on external communication have been issued by the Director-General of the Service and the secret service nature of the organization should be acknowledged, the information content available on the Service’s website does not help the organization’s direct social acceptance and integration.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

Acknowledgment

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Vol. 20, 2021, is supported by the United States government.

About the Author

Andras Hugyik, Ph.D. in military science, is a retired police colonel, a Chief Councilor of the Hungarian Police. He is a military engineer, investigator, and political expert. He is a former adviser to GUAM, OSCE, EUBAM, and UN – OPCW Joint Investigation Mechanism. Before joining the international organizations, he served in the Military Intelligence Office, the Protective Service of Law Enforcement Agencies, and the Counterterrorism Center of Hungary.

E-mail: seniorhugyik@gmail.com

- 13703 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML