NATO’s Defense Institution Building in the Age of Hybrid Warfare

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 17, Issue 3, p.39-51 (2018)Keywords:

capacity building, Defense Institution Building, DIB, Hybrid threats, hybrid warfare, security, StabilityAbstract:

Defense Institution Building (DIB) plays a crucial role in NATO’s “Projecting Stability” agenda by assisting Partners in developing their defense and security sectors, thereby increasing not only their security, but also that of the Euro-Atlantic region. At the same time, the current security environment is defined by complex and diffuse threats coming from both state and non-state actors, where the adversary aims at incapacitating the state. For this reason, increasing the resilience of the defense and security institutions against the hybrid threats in particular is key – a reality which should inform adaptation of the NATO’s DIB instruments.

This article discusses a number of key implications of the hybrid warfare for NATO’s DIB policies and processes, emphasizing that capacity building should aim to help the state institutions increase their ability to recognize and respond to hybrid warfare and, if necessary, to sustain the functioning of the state and its institutions under hybrid warfare conditions.

Introduction

Projecting stability through increasing resilience of NATO partners’ institutions or using their unique experiences as elements maximizing the effectiveness of collective response strategies works to the advantage of NATO. By making its Partners more secure and able to effectively respond to challenges to their security, as well as by working with them to confront common threats, NATO directly contributes to security and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area. At the same time, insecurity and vulnerability of Partners negatively influence Allied security.

It is likely that in the 21st century NATO will continue to “come under increasing challenge from both state and non-state actors who use hybrid activities that aim to create ambiguity and blur the lines between peace, crisis, and conflict.” [1] As experiences from Ukraine and elsewhere show, one of the key objectives of hybrid warfare is to paralyze the state, thereby creating conditions for furthering political and operational objectives of adversary.

It logically follows that if it usually is the state, which is the key target of a hybrid attack, then its defense and security institutions and their ability to repel attack are critically important. Therefore, one of the most effective strategies to prevent, counter, and—if necessary—respond to the use of hybrid warfare against the state is through making the state institutions more resilient to hybrid attacks through developing their institutional capacities. Such capacity building should aim to help the state institutions increase their ability to recognize and respond to hybrid warfare and, if necessary, to sustain the functioning of the state and its institutions under hybrid warfare conditions. These assumptions seem to be particularly relevant in the context of developing a role which the Defense Institution Building (DIB) should play in increasing the institutional resilience as part of the Alliance’s efforts aimed at “Projecting Stability.”

This article discusses a number of key implications for NATO’s DIB policies and processes which “the age of hybrid warfare” has brought about, proposes a possible framework within which to develop a new strategic approach to NATO’s DIB so that it better responds to the realities of the 21st-century conflict, and sets out an idea of a professional development program to be established by NATO, Allies and relevant Partners with a view to increasing their institutional capacities in the area of preventing, countering, and responding to hybrid threats. To these ends, the paper first briefly discusses the origins of DIB and hybrid warfare concepts before making an attempt to discuss key implications of hybrid threats for NATO’s DIB, proposing a possible new model of NATO’s DIB policy framework and, finally, offering a proposal for a possible professional development initiative.[2]

Origins of DIB

The end of the bi-polar world and the rise of intrastate violence in which non-state actors such as terrorist and criminal organizations thrive, led to recognition that development and security go hand in hand, and resulted in the “operating environment” that “was characterized by humanitarian interventions to end conflict, often coupled with peacekeeping operations to prevent violence from reigniting in post-conflict environments.” [3]The post- Cold War security world has thus been dominated by the concept of “human security” [4] defined by development efforts to strengthen the weak states, so that they were capable of protecting their own populations and territories, thereby contributing to regional stability.

This “nexus between development and security” [5] guided the development of the concept of Security Sector Reform (SSR), which called for a “holistic approach to enhancing partner capacity in all aspects of the security sector. The SSR approach would achieve this by improving the governance, oversight, accountability, transparency, and professionalism of security sector forces and institutions, in line with democratic principles and the rule of law.” [6] In turn, the SSR approach laid the theoretical foundations of DIB.

The post 9/11 environment has seen yet another shift towards the focus on capacity building of strategic partners as “effective counterterrorism relied on the ability of states to defend their own territory and secure their own populations.” [7] Furthermore, the mixed results of external assistance to failed states has led to the recognition that institution building is the key to successful conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

Conceptualizing DIB

Indeed, defense institutions are central to any state’s capacity to protect its citizens and territory. Therefore, “DIB is based on the recognition that in order to be effective defense partners, countries need professional defense sectors, which in turn require functioning defense institutions.” [8] The agenda of DIB is thus rather ambitious—going beyond delivering security assistance in terms of providing tools—and focusing on building the institutional capacity of key partners: “As a discipline, [DIB] is a unique blend of security assistance and institutional capacity building. It is distinct from most assistance programs targeting partner defense sectors in that it focuses on institutional capacity rather than tactical or operational mission readiness.” [9]

DIB is generally organized around two primary objectives. The first is to enable a partner nation to improve its ability to provide for its own defense, including by undertaking roles and missions that benefit shared security interests. The second objective is to empower a partner nation to undertake reforms within its defense sector that achieve greater transparency, accountability, efficiency, legitimacy, and responsiveness to civilian oversight.” [10]

Therefore, DIB activities focus “on enhancing the systemic capabilities involved in governing the defense sector.” [11] As a result, despite its activities being primarily situated within the defense sector, a whole range of institutional actors usually need to be involved. These actors could be divided into three levels [12]:

- the Ministry of Defense, as well as other ministries and overseeing bodies responsible for external and internal security;

- military headquarters translating ministerial-level policy into actual military policies and vested in the organization, training, and equipping of forces;

- the operational level which includes operational commands.

NATO and DIB

NATO’s own approaches to DIB are guided by the Partnership Action Plan on Defense Institution Building (PAP-DIB). Adopted back in 2004, after long consultation with Partners, the PAP-DIB was the first attempt at concretizing, in a more systematic fashion, NATO’s DIB policy offered to Partners. It provided a policy framework within which to promote practical co-operation in institutional reform and restructuring.

As every other policy framework, the PAP-DIB reflected political, policy, security and institutional realities at the time of its development which, in its case, indicated the necessity to further operationalize the Partnership for Peace (PfP) through the introduction of practical instruments. Influenced by experiences from NATO’s enlargement and the Partnership for Peace (PfP), the PAP-DIB focuses on the “democratization” and “civilianization” of defense institutions, including recognition of the role which they play in ensuring democratic progress and maintaining stability. It is also in its entirety that the PAP-DIB reflects Allied concepts of democratic oversight of defense institutions, as well as factors which are key to the successful institutional design of defense sectors.

The main premise of the PAP-DIB is that the establishment of effective, legitimate and democratic institutions able to support the state in delivery of security is one of the key building blocks to ensure long-term security and stability. Therefore, the document extends its scope into areas such as effective and transparent arrangements for the democratic control of defense activities; civilian participation in developing defense and security policy; effective and transparent legislative and judicial oversight of the defense sector; enhanced assessment of security risks and national defense requirements, matched with developing and maintaining affordable and interoperable capabilities; optimizing the management of defense ministries and other agencies which have associated force structures; compliance with international norms and practices in the defense sector, including export controls; effective and transparent financial, planning and resource allocation procedures in the defense area; effective management of defense spending as well as of the socio-economic consequences of defense restructuring; effective and transparent personnel structures and practices in the defense forces; and effective international co-operation and good neighborly relations in defense and security matters.

In 2018, a significant number of NATO’s DIB tools and instruments including the Building Integrity (BI), the Defense Capacity Building initiative (DCB), the Defense Education Enhancement Program (DEEP), the Military Career Transition Program (MCTP), and the Professional Development Program (PDP) continue to reflect in their activities the PAP-DIB objectives. The question arises, however, does “the age of hybrid warfare” necessitate strategic changes to or adaptation of the Alliance’s DIB, including possible development of new DIB policies and tools to help Allies and Partners better respond to the hybrid challenge.

The Age of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid warfare has become both one of the prevailing trends in the modern warfare and a much-evoked term in the military and political discourses. The term “appeared at least as early as 2005 and was subsequently used to describe the strategy used by the Hezbollah in the 2006 Lebanon War. Since then, the term “hybrid” has dominated much of the discussion about modern and future warfare” [13] and gained further prominence in the aftermath of the Russian annexation of Crimea. Yet, hybrid warfare remains a controversial term as some have argued that it is a “catch all” term used to simply describe the modern warfare which is not restricted to conventional means.

The popularization of the term “hybrid warfare” can be attributed to American military theorist, Frank Hoffman, who made an attempt [14] to capture the complexities of the modern warfare which consists of various actors using both regular and irregular types of warfare depending on how that suits their purposes. The consequence of this “blurring of modes of war, the blurring who fights, and what technologies are brought to bear” is “a wide range of variety and complexity that we call Hybrid Warfare.” [15]

For J.J. McCuen, hybrid wars are “full spectrum wars with both physical and conceptual dimensions: the former, a struggle against an armed enemy and the latter, a wider struggle for, control and support of the combat zone’s indigenous population, the support of the home fronts of the intervening nations, and the support of the international community.” [16]

On its part, NATO conceptualized hybrid warfare in 2010 in its Bi-Strategic Command Capstone Concept, which stated that hybrid threats:

are those posed by adversaries, with the ability to simultaneously employ conventional and non-conventional means adaptively in pursuit of their objectives […] Hybrid threats are comprised of, and operate across, multiple systems/subsystems (including economic/financial, legal, political, social and military/security) simultaneously […] [17]

At its Brussels Summit in July 2018, NATO Heads of State and Government further shed light [18] on the Alliance’s understanding of and identified NATO’s responses to hybrid warfare.[19]

NATO’s definition of hybrid warfare is rather broad, encompassing a wide range of actors, tactics and strategies. Therefore, examples of hybrid threats could include terrorist organizations like Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and ISIL/Da’esh, the operations of state-affiliated hackers, armed criminal groups and drug cartels, the use of resource-dependency between countries for political purposes or covert operations such as Russia’s strategic use of special forces (i.e. “green men”) and information in Ukraine.[20] It is, therefore, evident that “hybrid warfare does not represent the defeat or the replacement of ‘the old-style warfare’ or conventional warfare by the new. But it does present a complicating factor for defense planning in the 21st Century.” [21] Put differently, it is a warfare that escapes the clear divisions into categories, not because of the novelty of the tools used, but because of the integrated and systematic use of those tools.

That being said, it is important to be careful to not generalize from the specific.[22] “Hybrid wars are complex, because they don’t conform to a one-size-fits-all pattern. They make the best use of all possible approaches, combining those which fit with one’s own strategic culture, historical legacies, geographic realities, and economic and military means.” [23] Therefore, hybrid wars ought to be understood in their particular contexts.

Russia’s Model of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid warfare became a core security issue in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of the Crimea and the ongoing crisis in the eastern Ukraine. Indeed, the Russian course of action in Ukraine can be used as a classic example of hybrid warfare designed for a specific political, social, and cultural environment. It was even argued that “Russia serves as an excellent example in support of [this] understanding of hybrid warfare. It does not possess sufficient resources to win a conventional war against NATO. Consequently, civil means must be used to the greatest extent possible. Thus, a strategy to compete with the West necessarily becomes hybrid.” [24]

In other words, hybrid warfare in the case of Russia reflects “Russia trying to play a great power game without a great power’s resources.” [25] Furthermore, it also reflects the current context: the age of globalization. “Power dynamics are no longer based on just material means and increasingly focus on the ability to influence others’ beliefs, attitudes and expectations – an ability that has been boosted enormously by new technology.” [26]

Furthermore, in correspondence with the previous section, “the ‘surprise’ of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine was not generated primarily by the tools used (deception and disinformation campaigns, economic coercion and corruption, which all play a supportive role for military action) but rather by the efficiency and versatility with which they were employed in the Crimea and beyond. The novelty, in other words, was how well old tools were utilised in unison to achieve the desired goal.” [27]

In the same vein, Chivvis summarizes the following key characteristics of the Russian warfare:

- it economizes the use of force (Russia avoids using military force as it is inferior to NATO’s one);

- it is persistent (Russia’s hybrid war breaks down the traditional binary delineation between war and peace as it is always under way);

- it is population-centric (Russia intentionally seeks popular support through information operations).[28]

Further elaborating on the specificities of the Russian model of hybrid warfare, Kankowski states that “its effectiveness is grounded in military instruments. These consist for example of unjustified concentration of troops at the borders, large-scale snap exercises based on offensive scenarios, the use of provocative maneuvers in international airspace and at sea as well as the use of the (in)famous “little green men,” but also cyber-attacks, aggressive media campaigns, and other activities. One of the main features of the Russian model is deniability. How many times did we hear from the Russian side such statements as “there are no Russian troops in Ukraine” or “Russia is not providing arms to the separatists”?” [29]

This view is supported by Thornton, who argues that Russia’s hybrid warfare campaign is notable for the synergy created between the civilian and military activities which is controlled by the military itself.[30]

The Age of Hybrid Warfare and NATO’s DIB

In considering the impact of “the age of hybrid warfare” on NATO’s DIB, the central question which needs to be addressed is that of the continuing relevance of the PAP-DIB to the new security conditions including hybrid threats.

In this author’s view, an important aspect of the PAP-DIB is that it seems to have been developed based on the assumption that institutional reform in Partners’ defense sectors, including the establishment of effective mechanisms of civil and democratic control of security forces, would be implemented under “static,” peacetime conditions – a notion which appears to be particularly important in the context of the state exercising or re-establishing such control under hybrid warfare conditions. At the same time, when confronted with hybrid threats, the state and its defense institutions are often tempted to employ undemocratic measures to regain control. Indeed, it can be argued that if the primary target of hybrid adversaries is the democratic state, it is equally possible that one of the objectives of these adversaries is for the state to start to behave in undemocratic ways or lose control of its security sector. It is, therefore, of paramount importance for the state to examine and refine the existing mechanisms of civil and democratic control of its security forces to be used in hybrid contingencies and emergency situations. Overall, the question of civil and democratic control of security forces under hybrid warfare conditions should become one of the key elements of NATO’s DIB.

In addition, the central principle of the PAP-DIB—the need to establish civil and democratic control of defense institutions—remains valid but does not seem to be conceptually sufficient as a guiding principle to inform development of NATO’s DIB activities “in the age of hybrid warfare.” Due to their multidimensional nature, hybrid threats have redefined the conditions under which DIB policies should be formulated and implemented. The “old line” dividing national security into “external” and “internal” has eroded and sectoral strategies focused on individual components of the security sectors appear to no longer work due to the fact that the state defense institutions are not the only responders to hybrid warfare contingencies. They are rather the nucleus around which to build national responses to hybrid threats including contributions from other actors such as internal security forces, intelligence agencies, border security forces, and state-owned media, as well as non-state actors – private sectors, civil society organizations or even religious institutions. Consequently, the ultimate success of DIB interventions in “the age of hybrid warfare” often depends on taking a holistic approach to a national security architecture of a Partner nation with a specific focus of DIB requirements, with analysis being placed on the ability of the complete security sector to effectively prevent, counter and respond to hybrid threats.

Therefore, “DIB in the age of hybrid warfare” should be developed as one of the elements of the national security architecture transformation/adaptation to hybrid conditions, and not just an isolated activity principally focusing on defense organizations. In doing so, due to its expertise in defense matters, NATO could concentrate on the provision of expertise in defense-related aspects of managing hybrid warfare, while promoting the introduction of mechanisms to facilitate the establishment of links between defense ministries and other security sector organizations, at the same time. The point of departure for developing such a program of work is identification of the role which defense institutions play in responding to hybrid warfare as part of a wider national framework.

Secondly, the reality of hybrid conflict has also had an impact on defense institutions in terms of their ability to develop effective responses to hybrid threats. This, in turn, necessitates the expansion of DIB efforts into institutional restructuring and adaptation for the defense sectors to be able to prevent, counter, and respond to hybrid threat. In this context, broadening the scope of NATO’s DIB for it to include relevant capacity building aspects of institutional resilience would be in line with the guidance which the Allied Heads of State and Government provided at their Brussels summit in July 2018, where they reaffirmed their determination to help NATO’s Partners “to build stronger defence institutions, improve good governance, enhance their resilience [emphasis mine], provide for their own security, and more effectively contribute to the fight against terrorism.” [31] As a result, developing institutional resilience should become an integral component of NATO’s DIB. Key examples of such resilience seem to include the following areas:

- national security architecture preparedness;

- situational awareness;

- defense planning;

- cyber defense;

- Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP);

- strategic communications;

- interagency coordination and establishing operational links with non-governmental actors.

Thirdly, NATO might also need to establish its own NATO/PfP hybrid response team: a permanent or semi-permanent capability composed of civilian-military experts to be deployed on request to assist a Partner nation in preventing, countering or responding to hybrid threat. Although the core of the capability could revolve around DIB, it also would need to extend to expertise outside DIB. In case NATO lacks expertise in certain areas (the Ministry of the Interior, as an example), it could draw on national expertise which interested Allies and Partners could provide or forge cooperation links with other international organizations which are more specialized in such issues. Given that some of the NATO Partners have become providers, not just recipients of hybrid warfare expertise, their experts could also be attached to the team.

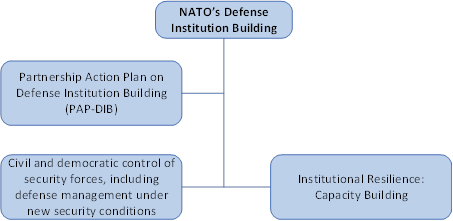

Figure 1: Possible New NATO’s DIB Framework.

Finally, the Alliance might need to assess how the whole portfolio of its existing DIB programs and activities contribute to addressing the requirements of “the age of hybrid warfare.” It might also need to consider aligning its DIB conceptual approaches to new security conditions, of which the hybrid threats are and will continue to be a prevailing feature, as well as launching new long-term DIB interventions to help its Partners better respond to hybrid threat. One of the first long-term initiatives which might spring from such an analysis could be focused on increasing skills of those employed in the defense and security institutions so that they are able to manage national and Allied responses to hybrid warfare.

Professional Development Program on Hybrid Warfare as a Starting Point?

Understanding the nature of the hybrid threat is key if the state is to effectively respond to it. In this context, increasing relevant skills of key personnel employed in the defense institutions of national administrations in Allied and Partner countries so that they could develop strategies for the state to be able to recognize, respond to, and—if necessary—operate under hybrid conditions should be seen as a key contribution which NATO’s DIB could offer to addressing the hybrid challenge. As a practical proposal, the Alliance and/or interested Allies and relevant Partners could explore the possibility of developing a new cooperation mechanism with interested Partners to increase institutional capacities in the area of hybrid warfare – a Professional Development Program on Hybrid Warfare (PDP/HW).

A key objective of the PDP/HW would be to provide a capacity building framework to establish resilience to hybrid threats within Allied and relevant Partner countries’ national administrations and wider national communities.

The PDP/HW would specifically aim to:

- identify roles which individual components of the security sector, including defense institutions, play in contributing to national responses to hybrid warfare;

- facilitate development of national policies aimed at establishing functional partnerships between state institutions, security forces, civil society and business communities, thus preparing the society, taken as a whole, for the challenges of modern warfare, including hybrid warfare;

- assist in developing or increasing state capacities to deter or prevent the application of hybrid warfare against the state and its institutions;

- provide relevant education, training and exercise opportunities to civilian authorities of Allied and Partner countries;

- create conditions for developing other forms of cooperation between NATO and other nations in identifying challenges of and developing responses to modern hybrid warfare;

- provide a platform to generate expertise in and facilitate research activities focusing on the role of national administration in preventing, countering and responding to hybrid warfare.

The PDP/HW would provide a framework within which relevant Partners and interested Allied nations would group together to develop a capacity building initiative which would be used to establish resilience to hybrid threats within their national institutions and create synergies of action at national and international levels. In other words, relevant Partners, including those with an experience in confronting hybrid threats, would not only receive assistance but also offer their knowledge and experience to promote development of effective hybrid warfare responses.

A key component of the PDP/HW could be the PDP Hybrid Warfare course covering the entire spectrum of issues pertinent to hybrid war and hybrid warfare. The general objective of the course would be to inculcate state institutions and selected members of societies with knowledge and awareness of hybrid warfare. Participation in the course would be open to political institutions, civil service, defense and security organizations and the military. Relevant representatives of business communities, media and civil society could also be invited to participate in the course.

Conclusion

The age of hybrid warfare has reshaped the security environment in the Euro-Atlantic area by producing a shift from counter-terrorism, peace-keeping missions and warfighting in places such as Afghanistan to multidimensional threats “blurring the line between peace, crisis, and conflict.” This strategic change should inform adaptation of the NATO’s DIB instruments for them to contribute to developing effective responses to hybrid warfare. Although NATO should still encourage the maximum use of the existing instruments, tools and institutional networks to pursue its DIB objectives, there is a clear need for the Alliance to come to conclusion about expanding its DIB policies into developing institutional resilience to hybrid threats. Focusing on the role which skills of those employed in national administrations play in preventing, countering and responding to hybrid warfare through establishing the NATO PDP/HW could be one of the aspects of this new agenda of action and the best contribution which NATO’s DIB could offer to address the challenges of “the age of hybrid warfare.”

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

About the Author

Marcin Kozieł works at the Political Affairs and Security Policy Division (PASP) of the NATO International Staff, NATO HQ, Brussels. From 2009 till 2015 he was Director of the NATO Liaison Office in Kyiv, Ukraine.

E-mail: koziel.marcin@hq.nato.int.

[1] NATO, “Brussels Summit Declaration, Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels 11-12 July 2018,” Brussels, July 11, 2018, para 21,https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm#21.

[2] The author would like to thank LTC Janne Mäkitalo, Military Professor, Department of Warfare, National Defense University, Finland, whose ideas were a source of inspiration for the proposal of the NATO/DIB Professional Development Program on Hybrid Warfare.

[3] Alexandra Kerr, “Defense Institution Building: A New Paradigm for the 21st Century,” in Effective, Legitimate, Secure: Insights for Defense Institution Building, ed. Alexandra Kerr and Michael Miklaucic (Washington DC: Center for Complex Operations, Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, 2017), ix-xxvii.

[4] Kerr, “Defense Institution Building,” xi.

[5] Kerr, “Defense Institution Building,” xii.

[6] Kerr, “Defense Institution Building,” xii.

[7] Kerr, “Defense Institution Building,” xiii.

[8] Kerr, “Defense Institution Building,” xv.

[9] Thomas W. Ross, Jr., “Defining the Discipline in Theory and Practice,” in Effective, Legitimate, Secure: Insights for Defense Institution Building, 21-46.

[10] Ross, “Defining the Discipline in Theory and Practice,” 25.

[11] Ross, “Defining the Discipline in Theory and Practice,” 26.

[12] Ross, “Defining the Discipline in Theory and Practice,” 28-29.

[13] Damien Van Puyvelde, “Hybrid War – does it even exist?” NATO Review Magazine, 2015, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/2015/Also-in-2015/hybrid-modern-future-warfare-russia-ukraine/EN/.

[14] Frank Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Warfare (Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007).

[15] Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century, 14.

[16] John J. McCuen, “Hybrid Wars,” Military Review 88, no. 2 (March-April 2008): 107-113, 108, http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/milreview/mccuen08marapr.pdf.

[17] BI-SC Input to a NEW Capstone Concept for the Military Contribution to Countering Hybrid Threats (Brussels: NATO, 2010), 2-3. http://www.act.nato.int/images/stories/events/2010/20100826_bi-sc_cht.pdf.

[18] NATO, “Brussels Summit Declaration,” para 21 and 72.

[19] NATO, “NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats,” last modified July 17 2018, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_156338.htm?selectedLocale=en.

[20] European Parliamentary Research Service Blog, “Understanding Hybrid Threats,” last modified June 24, 2015, https://epthinktank.eu/2015/06/24/understanding-hybrid-threats/.

[21] Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century, 9.

[22] Chris Tuck, “Hybrid War: The Perfect Enemy,” Defence-in-Depth: Research from the Defence Studies Department (London: King’s College, 2017), https://defenceindepth.co/2017/04/25/hybrid-war-the-perfect-enemy/.

[23] Guillaume Lasconjarias and Jeffrey A. Larsen, “Introduction,” in NATO’s Response to Hybrid Threats, ed. Guillaume Lasconjarias and Jeffrey A. Larsen (Rome: NATO Defense College, 2015), 1-13.

[24] Uwe Hartmann, “The Evolution of the Hybrid Threat, and Resilience as a Countermeasure,” Research Paper no. 139 (Rome: NATO Defense College, September 2017), 1-8.

[25] Mark Galeotti, “Russia’s Hybrid War as a Byproduct of a Hybrid State,” War on the Rocks, December 6 2016, https://warontherocks.com/2016/12/russias-hybrid-war-as-a-byproduct-of-a-hybrid-state/.

[26] Lord Jopling, “Countering Russia’s Hybrid Threats: An Update,” Draft Special Report (NATO Parliamentary Assembly, 27 March 2018), https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=sites/default/files/2018-04/2018 - COUNTERING RUSSIA'S HYBRID THREATS - DRAFT SPRING REPORT JOPLING - 061 CDS 18 E.pdf.

[27] Nicu Popescu, “Hybrid Tactics: Russia and the West,” Issue Alert 46 (Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies, October 2015): 1-2, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Alert_46_Hybrid_Russia.pdf.

[28] Christopher S. Chivvis, “Understanding Russian ‘Hybrid Warfare’: And What Can Be Done About It,” Testimony Before the Committee on Armed Services United States House of Representatives (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, March 22, 2017), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/CT400/CT468/RAND_CT468.pdf.

[29] Dominik P. Jankowski, “Hybrid Warfare: A Known Unknown?” Foreign Policy Association, July 18, 2016, http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2016/07/18/hybrid-warfare-known-unknown/.

[30] Rod Thornton, “Turning Strengths into Vulnerabilities: The Art of Asymmetric Warfare as Applied by the Russian Military in its Hybrid Warfare Concept,” in Russia and Hybrid Warfare – Going Beyond the Label, ed. Bettina Renz and Hanna Smith, Aleksanteri Papers 1 (2017), 52-60, 55, http://www.helsinki.fi/aleksanteri/english/publications/presentations/papers/ap_1_2016.pdf.

[31] NATO, “Brussels Summit Declaration.”

- 12894 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML