Cybersecurity in Switzerland: Challenges and the Way Forward for the Swiss Armed Forces

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 19, Issue 1, p.63-72 (2020)Keywords:

crisis management, Cyber defence, cyber operations, cyber risks, cybersecurity strategy, law enforcement, resilienceAbstract:

The cybersecurity policy of Switzerland is focused on enhancing competencies and knowledge, investing in research and the resilience of critical infrastructures, threat monitoring, supporting innovation, promoting standards, and increasing awareness – all in the framework of public-private, inter-regional, and international cooperation. The armed forces support this policy by developing threat intelligence and attribution capabilities, readiness to undertake active measures in cyberspace, and to ensure operational availability under any circumstances.

Policy Highlights

Like in any other European state, cybersecurity has grown in importance in Swiss politics. And although Switzerland’s cybersecurity and defense policies are still a work in progress, the nation has made tremendous efforts in getting cybersecurity policies, roles, and responsibilities right.

Published in 2018, the “National Strategy for the Protection of Switzerland against Cyber Risks” is the main policy document that guides Swiss ambitions and replaced the 2012 strategy. Overall, the strategy sets seven strategic goals and ten spheres of action. The goals can be summarized as preparing Switzerland to face the cyber risks of tomorrow head-on, by building up cybersecurity competencies, crisis management structures, strengthening resilience, and facilitating international cooperation.

The strategy is accompanied by an implementation plan, which was the result of three consultations with the main stakeholders in the Swiss cybersecurity landscape. While the steering of the strategy is centrally organized, its implementation is decentralized with a clear distribution of roles. The implementation plan sets out specific measures to implement the ten spheres of action defined in the 2018 strategy. It also clarifies responsibilities, outlines quantifiable objectives, and maintains a schedule to evaluate implementation progress.

The Swiss Reporting and Analysis Centre for Information Assurance (MELANI) is the institution responsible for writing and implementing the strategy, and informing the Swiss population and the private sector on any new cyber threats.

Another important document is the Cyber Defense Action Plan 2017 for the Federal Department of Defense, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS). The Action Plan defines the role of the DDPS, the Federal Intelligence Service (FIS), and the armed forces within the Swiss cybersecurity landscape. Overall, their role is to protect the DDPS’ networks and critical infrastructures from cyber threats, conduct military and intelligence cyber operations, and support civilian critical infrastructures in case of a major cyberattack.

The Swiss political landscape has undergone considerable changes during the past few years. In 2016, the Federal Council published its report on Swiss security policy, which underlined the risks caused by information technologies and the changing nature of conflict with regard to cyberspace. The Swiss Parliament passed a new intelligence law, which came into force in 2017, and the military law was revised in 2018 to allow the armed forces to have the means to protect their networks and conduct offensive cyber countermeasures. The Federal Council also recently launched a Federal Council Cyber Committee as a driver for increased centralization in the cybersecurity sphere, which is unusual for Switzerland. As a federal state, the preference is to leave a certain leeway to the 26 cantons and the private sector. The Cyber Committee is also in charge of monitoring the implementation of the national cybersecurity strategy.

These political developments show that the Swiss government takes cybersecurity issues seriously by treating them at the highest political levels. The Federal Council has also created a Cyber Security Competence Centre, which functions as a single point of contact for all cybersecurity issues at the national level. It also coordinates the implementation of the national strategy. Finally, the latest development has been the nomination of a delegate for cybersecurity who not only steers the cybersecurity strategy but also heads the special federal committee on cybersecurity and represents the Swiss Confederation in other committees.

Policy Challenges

The National Strategy for the protection of Switzerland against cyber risks tackles a broad set of cybersecurity issues. As such, it encompasses the development of technical capabilities, streamlining education, fighting cybercrime, strengthening the military, increasing international cooperation, and raising awareness. While the strategy is specifically focused on cybersecurity, it also naturally aligns with Switzerland’s national security policy of 2016, the Federal Council’s strategy for a digital Switzerland 2018, the national strategy on critical infrastructure protection 2018-2022, and integrates the recent changes in the intelligence and the military law.

Overall, the strategy underlines the necessity of developing public-private partnerships and closely engaging with the private sector on the one hand and insists on the subsidiary role of the state on the other. With regard to the armed forces, the strategy mentions the need to develop defensive capabilities but also to ensure the armed forces’ ability to undertake active measures in cyberspace. These active measures are understood as ways and means to disturb, prevent, or slow down an adversary targeting Swiss critical infrastructure. Additionally, the strategy also specifies that Switzerland has an active role to play in shaping cyber norms at the international level and cooperate with other nations. Finally, the strategy underlines the importance of raising public awareness of cybersecurity issues. The strategy covers all of these elements in the following ten spheres of action:

1. Building competencies and knowledge

- Measure 1: monitoring of trends in technological innovations

- Measure 2: improvement of the research and education in cybersecurity

- Measure 3: establishment of frameworks that would encourage innovation in cybersecurity

2. Threat landscape

- Measure 4: improvement and extension of capabilities in analysis and presentation of the cyber threat landscape

3. Resilience management

- Measure 5: improvement of the resilience of critical infrastructures

- Measure 6: improvement of the resilience of the federal administration networks

- Measure 7: improvement of the resilience of cantons’ networks through information and experience sharing

4. Standardization/Regulation

- Measure 8: definition and introduction of minimum standards to improve network resilience

- Measure 9: start of a review on an obligation to report cyber incidents

- Measure 10: more involvement of Switzerland in international governance of the Internet to ensure the development of a free and democratic Internet

- Measure 11: establishment of expert groups to evaluate regulations regarding cybersecurity

5. Incident management

- Measure 12: development of MELANI as a Public-Private Partnership

- Measure 13: offering MELANI services to all types of enterprises

- Measure 14: development of the collaboration between the Swiss government and other centers of competence

- Measure 15: establishment of a process to clearly define responsibilities in cyber incident management within the federal administration

6. Crisis management

- Measure 16: integration of cyber experts in crisis management cells to foster collaboration with the private sector, if needed

- Measure 17: organization of joint exercises in crisis management with the integration of cybersecurity elements in larger exercises and the organization of cyber-specific exercises

7. Prosecution

- Measure 18: establishment of a table of the current cybercrime violations in Switzerland

- Measure 19: enhancement of the collaboration between the various competence centers and the national network of investigators specialized in cyber criminality

- Measure 20: development of the education for law enforcement to build knowledge regarding the prosecution of cybercriminal cases

- Measure 21: modification of the current structure of federal offices in charge of criminal affairs to establish a new Central Office on the fight against cyber criminality to enhance collaboration among cantons in cases of cyber criminality

8. Cyber defense

- Measure 22: development of threat intelligence and attribution capabilities

- Measure 23: ensuring the armed forces’ abilities to undertake active measures in cyberspace in accordance with the new legal basis

- Measure 24: development of the armed forces to ensure their operational availability in all circumstances

9. Active positioning of Switzerland in international cybersecurity policy

- Measure 25: involvement of Switzerland in early discussions in international forums concerning cybersecurity

- Measure 26: enhancement of international cooperation to improve capabilities and information sharing in cybersecurity

- Measure 27: establishment of bilateral and multilateral dialogs on foreign security policies regarding cybersecurity

10. Public impact and awareness-raising

- Measure 28: implementation of a communication strategy for the strategy

- Measure 29: raising awareness in the public about cyber risks.

The ten spheres of action and the enclosed measures mostly seek to develop existing structures and fill the gaps that have been identified in the 2012 national strategy. The main differences between the 2018 and 2012 strategy concern three spheres of action. The first difference concerns crisis management and awareness-raising. In the 2018 strategy, the population, small and medium enterprises, and cantons have been included among the target groups, while in the 2012 strategy, the focus was only on critical infrastructure operators. The second difference refers to the standardization and regulation. The 2018 strategy mentions an examination of a possible obligation to report cyber incidents and the evaluation and introduction of minimum standards for IT security in critical infrastructure. These new measures echo the European Union Network and Information Security (NIS) directive. The third difference relates to cyber defense. The 2018 strategy includes the armed forces’ role and responsibilities while they were almost totally absent from the first strategy.

Similar to the National Strategy for the protection of Switzerland against cyber risks, the Cyber Defense Action Plan (PACD) 2017 recognizes the need for a comprehensive approach to cybersecurity. The PACD 2017 acts as a roadmap for the DDPS to reinforce its cyber capabilities. The document seeks to highlight lessons learned from the RUAG cyberattack in 2016 and national cyber defense exercises. The PACD 2017 identifies five major fields in which the DDPS needed to make progress: strategic management, developing operational means, building support from the militia structure, improving collaboration with higher education and the private sector, and finding the workforce. The PACD 2017 mentions that since 2016 the DDPS has already started to take measures such as implementing an Information Security Management System (ISMS) according to the ISO 27000 series of standards and modernizing its systems and network infrastructure. The PACD 2017 is very transparent about the resources it needs to achieve its objectives.

Policy Implementing Structures and Whole-of-Nation Context

Switzerland is one of the most federalized and decentralized countries in the world. A large number of tasks are left to the cantons to manage, including education and law enforcement. This decentralization is sometimes perceived as a challenge and/or restriction for the federal government to tackle new issues like cybersecurity. Actually, the past years have shown that the trend on the issue of cybersecurity has been a move toward more centralization at the federal level.

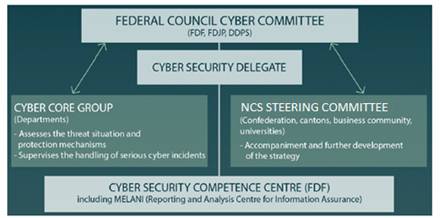

Coordination structure. With the new strategy, Switzerland has set up a new overarching structure with the Federal Council Cyber Committee, the cyber security delegate, and the Cyber Security Competence Centre. All these new institutions play a role in the coordination of cybersecurity at the federal level:

- Federal Council Cyber Committee: The Committee is composed of the heads of the Federal Department of Finance, the DDPS, and the Federal Department of Justice and Police (FDJP). The Committee meets four times a year and its role is to monitor the implementation of the national cybersecurity strategy;

- Cyber Security Delegate: The Federal Council is responsible for choosing the Cyber Security Delegate. The Delegate is responsible for steering the agenda of the Swiss Confederation at the federal level regarding cybersecurity issues. The Delegate heads internal committees on cybersecurity and represents Switzerland in other committees in Switzerland;

- Cyber Core Group: The group reports to the Federal Council Cyber Committee and is responsible for enhancing the collaboration between the three sectors: cybersecurity, cyber defense, and criminal prosecution. The group is in charge of ensuring a joint threat assessment and supervises through federal entities the management of cyber crises involving several Federal Departments;

Figure 1: Federal Cyber Risk Organization.

- NCS Steering Committee: The Committee reports to the Federal Council Cyber Committee and ensures that the implementation of measures from the strategy stays coordinated. The NCS Steering Committee also helps with suggestions for further policy developments;

- Cyber Security Competence Centre: The Centre is subordinate to the Federal Department of Finance and includes MELANI. The Centre is the single point of contact for cybersecurity issues at the federal level and ensures the coordinated implementation of the strategy.

Military roles and responsibilities: The armed forces are part of the DDPS. Their role is to protect and defend their own networks and critical infrastructure against cyberattacks, to support the FIS in responding to cyberattacks targeting civilian critical infrastructures, and to maintain capabilities in cyberspace in case of war. The conditions for the armed forces to support the FIS in defending against cyberattacks are very strict and the armed forces would only be involved as additional help. The Electronic Operations Centre (EOC) is the main actor for military cyber defense in the DDPS. The EOC is responsible for fulfilling the aforementioned tasks and collaborates with the FIS with regard to critical infrastructure. The EOC is composed of military and civilian personnel, the military conscripts working at the EOC report to the Command Support Brigade 41. With the revision of the military law, the armed forces can now conduct offensive cyber countermeasures with the authorization of the Federal Council.

Law enforcement role and responsibilities:

- Cantonal police forces: Fighting cybercrime or cyber-enabled crimes is the role of cantonal police forces. Each canton allocates resources and organizes its fight against cybercrime as it desires. The Canton of Zurich built a Cyber Security Center and is one of the cantons that invests the most in fighting cybercrime. On the other hand, smaller cantons have more limited resources and may not be able to build centers like in the Canton of Zurich. Cantonal police forces coordinate and exchange information on cybercrime in various national platforms such as the Swiss Conference of Chiefs of Cantonal Police, the Conference of Directors of Cantonal Departments of Justice and Police, the Swiss Security Network or the newly created Cyberboard, whose role it is to keep an overview on the cybercriminal violations in Switzerland;

- Federal Police (Fedpol): Fedpol is responsible for fighting organized crime, coordinating relations with foreign police forces, protecting people and buildings under the responsibility of the Swiss Confederation, and coordinating the identification processes (e.g., passports, IDs, immigration). Regarding cybercrime, Fedpol is only responsible for investigating cybercrime cases that fall under the jurisdiction of the Swiss Confederation (i.e., cybercrime linked to the areas of responsibilities mentioned above);

- Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland: The Attorney General is in charge of prosecuting cybercriminal cases that fall under the jurisdiction of the Swiss Confederation.

Intelligence role and responsibilities: The Federal Intelligence Service (FIS) is in charge of the counterintelligence and attribution, supports critical infrastructures targeted by cyberattacks, fights against terrorism in cyberspace, and conducts awareness-raising campaigns about cyber espionage. Until 2017, the FIS was limited to defensive measures in cyberspace. With the new law, the FIS has the legal basis to conduct offensive cyber countermeasures against infrastructures located outside Switzerland after authorization by the head of the DDPS who needs to confer with the heads of the FDFA and the FDJP first.

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) role and responsibilities: The Security Policy Division of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs is responsible for diplomatic measures like participating in international forums about cybersecurity norms, the development of international treaties on cybersecurity issues and Internet governance.

Policy Implementation

International cooperation: While Switzerland is neutral, it does not refrain from cooperating bilaterally or multilaterally with other countries. Switzerland has shown that it is aware that cybersecurity issues cannot be tackled alone. Regarding cybersecurity, Switzerland mainly collaborates through its intelligence service, its armed forces, and the FDFA. Since 2019, Switzerland is also a contributing partner of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) in Tallinn. This partnership allows Switzerland to access knowledge, information, and training but also to participate in various activities offered by the CCDCOE. Switzerland already took part in various international exercises such as Locked Shields, Crossed Swords, Cyber Coalition, Cyber Storm, and Cyber Europe. Switzerland also collaborates and exchanges regularly with its neighbors and other states regarding cyber threat intelligence and practices.

Through the FDFA, Switzerland is involved internationally to promote the development of international cyber norms in organizations like the UN and the OSCE. Switzerland participates in the United Nations Governmental Group of Experts (UN GGE) and chairs the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG). Switzerland wants to contribute to the discussion on the respect and application of international law in cyberspace and to establish trust among states regarding cybersecurity issues. Finally, Switzerland promotes itself and Geneva as a discussion platform for cybersecurity issues.

Engagement of private sector/NGOs/academia: In 2018, the DDPS launched the Cyber Defense Campus (CYD Campus), whose role is to serve as a research and development hub connecting the armed forces, academia, and the private sector. The CYD Campus is part of Armasuisse, the Federal Office for Defense Procurement, located in the DDPS. The CYD Campus is developing offices at the EPFL in Lausanne and the ETH in Zurich. The objective is to be as close as possible to startups and innovation, to monitor new technologies and talents, to do research, and to train talents. The CYD Campus should reach its full capacity by the end of 2020.

The DDPS also collaborates with the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences (SATW) to map research and development projects on cybersecurity in Switzerland. Additionally, DDPS assigned research projects on technical and non-technical topics linked to cybersecurity to higher education institutions.

Finally, the DDPS supports cyber competitions such as the 9/12 Strategy Challenge organized by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) and the Swiss Cyber Storm, to promote the field of cybersecurity and to find talents.

Conscription army: In August 2018, the Swiss armed forces launched a cyber defense training program for conscripts. The training program has the long-term objective to train 600 conscripts to become cybersecurity specialists that will be integrated into a cyber defense battalion.

The Way Forward

Because cybersecurity issues will continue to be significant challenges for states, Switzerland should continue with its recent developments and improvements that started during the past three years. Switzerland’s latest initiatives and policies relating to cybersecurity are new and it is still too early to evaluate and notice their effects. Time will tell if these measures will help Switzerland to face the cybersecurity challenges of tomorrow. However, recent measures will remain important for Switzerland in the coming years. International cooperation will remain significant because of the cross-border nature of cybersecurity. These challenges cannot be tackled alone and, therefore, Switzerland should continue to cooperate bilaterally and multilaterally. The cyber defense training program will regularly bring conscripts in the future cyber defense battalion. These new cybersecurity specialists will contribute to building capabilities and would benefit first the Swiss armed forces but also the whole society when they go back to their civilian life. Overall, Switzerland should continue its momentum and carry on with the implementation of its strategy and the buildup of its capabilities in the military and civilian institutions.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the contributing author and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

About the Author

Marie Baezner is a Researcher in the Cyber Defense Team of the Center for Security Studies. She holds an MA in International Security from the University of Bath, United Kingdom, and a BA in International Relations (Political Science and International Law) from the University of Geneva. Before joining the CSS, Marie Baezner has worked for the Command Support Basis of the Swiss Armed Forces and the Swiss Armed Forces Peace Support Mission in Kosovo. Marie Baezner’s research focuses on cyber incidents and cyber aspects of current conflicts. E-mail: marie.baezner@sipo.gess.ethz.ch.

- 17042 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML