The Rise of All

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 12, Issue 3, p.63-86 (2013)About the author*

Introduction: What Will the World Look Like in 2050?

In the 1950s, there was much speculation as to what would happen if mankind ventured into outer space. Both Soviet and U.S. scientists were forced to speculate about how objects would perform above the atmosphere without knowing what would truly happen. TIROS I, for example, was the first successful orbit-sustaining satellite, designed to map the earth’s weather. It was launched by the United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on 1 April 1960.[1] Thirty years later, NASA turned the TIROS technology around and started looking outward, towards deep space. In 1990, NASA launched the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit and created some of the most detailed visible-light images ever, thereby allowing a deep view into space and time. Many Hubble observations have led to significant breakthroughs in astrophysics. By taking modern theory from communications satellites and looking outward instead of toward Earth, or “reversing the lens,” scientists were able to discover a new universe. But could scientists have accurately predicted the Internet, a rover on Mars, or hypersonic travel in the 1950s?

In the field of political science, there is often a similar practice of taking previous observations and using them to try to build pictures of what world governments will look like in the future. Evidence would show, however, that there is a lack of current consensus among academics on what the world order will look like over the next fifty years. Will it finally be the end of Charles Krauthammer’s “Unipolar Moment” [2] for the United States, as the world transitions to Giovanni Grevi’s “Interpolar world”? [3] Or will the world develop an equilibrium solution to the “political trilemma” between global democracy, national determination, and economic globalization proposed by Harvard professor Dani Rodrik? [4] Perhaps it could develop into a “G-Zero” world, as proposed by Ian Bremmer, where every state fends for itself? [5] Additionally, what of the possibility that the U.S. might face a steady relative decline, while the remaining states experience Fareed Zakaria’s “Rise of the Rest”? [6]Particular difficulties arrive when trying to analyze the end of the Cold War, the rapid rise of Brazil, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS), the formation of the European Union, and the deep entrenchment of the global war on terror. With so many chaotic events, political scientists are left striving to paint a coherent picture that accurately predicts the future state of the world.

Sometimes, when scientists are left without a feasible theoretical basis for understanding effects in play, they look to other fields of study to identify an applicable method that might help them toward new discoveries in their own field. In the late 1980s, an air power theorist named Colonel John Warden developed an “Air Theory for the Twenty-first Century.” [7] This common-sense theory provided a “Five-Rings Model” lens through which strategic-level planners could examine a state and determine how best to go about dismantling a regime using the tool of military intervention. The theory breaks a state down into five basic centers of gravity (a concept proposed in the 1820s by the German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz), which military forces can then attack to impose strategic paralysis on an enemy. “Reversing the lens” of this theory, we can use the Five-Rings Model to examine how to build up (instead of surgically destroy) a state. However, the modern state is influenced by a factor that is much more prevalent now than in the late 1980s, when Warden developed his theory: globalization. Adding a sixth ring of globalization to the model adds another dimension to the lens with which we can examine the state. To completely understand the effects of this theory on the construct of global governance, we must first examine in more detail the Six Rings, which are Leadership, System Essentials, Infrastructure, Population, Fielded Military Forces, and Globalization. Second, we can look at each ring individually and translate what this would relate to in the political science spectrum. Next, we can organize our study of states by using groupings into six levels based on global functionality and power in order to simplify analysis. Finally, in a synthesis of these concepts, we can use a matrix of six rings and six levels to examine the construct of global states, and can anticipate an optimistic future that includes the “Rise of All.”

Warden’s Five Rings Model

In order to see how the world might come to support the “Rise of All,” we must first completely understand the methodology of Warden’s Five Rings model. John Warden first developed this model in the late 1980s while studying the effects of strategic military operations, particularly air operations. At the core of the Five Rings theory, Warden divides the various components of a few example “systems” into five main components. Each system, or “ring,” was considered one of the enemy’s centers of gravity, which is the source of strength of a state – in other words, it was an element so critical that, if it were removed, the state would have difficulty conducting business. Warden’s thesis provides four examples of the application of the Five Rings model, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Warden’s Five Main Components of System Analysis.[8]

| Body | State | Drug Cartel | Electric Company |

Leader | Brain, eyes, nerves | Government, communication, security | Leader, communication, security | Central control |

Organic essentials | Food/oxygen organic conversion | Energy: electricity, oil;food, money | Coca source plus conversion | Input: heat, hydro power Output: electricity |

Infrastructure | Blood vessels, bone, muscles | Roads, airfields, factories | Roads, airways, sea lanes | Transmission lines |

Population | Cells | People | Growers, distributors, processors | Workers |

Fighting mechanism (first responders) | Leukocytes | Military, police, firemen | Street soldiers | Repairmen |

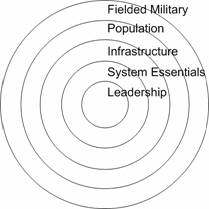

Warden then combined the five components in a mathematically inclined differentiation approach that creates a unique way of looking at the strategic centers of gravity that reversed the normal tactical-level thinking of the time. This strategic, or top-down approach, reorganizes his observations into the Five Rings theory model. The five rings, in order of importance, are leadership, system essentials, infrastructure, population, and fielded military forces, as shown in Figure 1.

The idea behind Warden’s Five Rings model was to simultaneously attack each of the rings to paralyze the enemy, an objective also known as physical paralysis. The effort in studying the enemy and understanding how they are organized would allow military planners to impose costs and lead directly into enemy paralysis via a technique called parallel war. To optimize a parallel war construct, the attacker engages as many rings as possible, with special emphasis on paralyzing the center ring, which is the enemy’s leadership.[9]

Figure 1: Warden’s Five Rings Model.

Warden’s theory was used to develop the strategic air campaigns of Operations Desert Storm (against Iraq in 1991), Allied Force (against the Milosevic-led Yugoslavia in 1999), Enduring Freedom (the ongoing campaign in Afghanistan, under way since 2001), and Iraqi Freedom (the 2003–11 war in Iraq), all of which provided some of the most rapid destructions of states that the world has ever observed. Warden himself summarized the application of the five rings model during Operation Desert Storm as follows:

Within a matter of minutes, the Coalition attacked over a hundred key targets across Iraq’s entire strategic depth. In an instant, important functions in all of Iraq stopped working. Phone service fell precipitously, lights went out, air defense centers stopped controlling subordinate units, and key leadership offices and personnel were destroyed. To put Iraq’s dilemma in perspective, the Coalition struck three times as many targets in Iraq in the first 24 hours as [the] Eighth Air Force hit in Germany in all of 1943.[10]

Warden’s theory is not without opponents, however. A U.S. Air Force Air War College analyst, Major Howard Belote, points out that, “unlike a human body, a society can substitute for lost vital organs, and metaphor-based theories have led to faulty employment of airpower in war because they fail to see that conflict is nonlinear and interactive.” [11] Though many could also point to the achieved end-state of several of the listed campaigns, political objectives notwithstanding, the efficiency with which these operations achieved their purely military objectives stands sacrosanct. Or, as Warden himself states, “Its imperfection does not erase its utility. If bold ideas, unjustified anticipations, and speculative thought are our only means …we must hazard them to win our prize.” [12] Let us then accept that Warden’s theory provides the starting point of a model that may prove useful to observe the development of the modern state.

Globalization

Many political scientists argue that the primary forces currently at work on the states of the world are those of globalization. First, let us define these forces, so we are better able to understand their effects in combination with Warden’s previously identified five rings. Manfred B. Steger has defined globalization as a “social condition, characterized by tight global economic, political, cultural and environmental interconnections and flows that make most of the currently existing borders and boundaries irrelevant.” [13] He also suggests that five main claims exist about globalization:

- Globalization is about the liberalization and global integration of markets

- Globalization is inevitable and irreversible

- Nobody is in charge of globalization (it happens by accident)

- Globalization benefits everyone

- Globalization furthers the spread of democracy in the world.[14]

In each of the five rings, we can observe the forces of globalization in effect. Take, for example, the leadership ring, which covers the governments of the world. The political origins of the modern state trace back to the Pax Romana, the early Renaissance, and the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.[15] Politically, we have observed a great expansion and intensification of interrelations between states around the world over the last century. Steger lists the United Nations, the European Union, the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and NATO as examples of this globalization.[16] The leadership ring also consists of hundreds of worldwide and non-governmental associations (NGOs) like Greenpeace or Amnesty International.[17]

The system essentials ring, consisting of the economy and energy sectors, may best portray the effects of globalization. Strategist Thomas Barnett suggests “the global economy is the ultimate service-oriented architecture that nobody quite controls even as almost everybody avails himself of its connectivity, adding transactions to its volume every day.” [18] This did not happen overnight, and has, in fact, taken centuries to build. In the post-World War Two era, for example, the Bretton Woods conference established three new international economic organizations. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) administers the monetary structure and transfer of currencies among nations. The International Bank for Reconstruction collected donor monies and distributed funds to building or recovering economies. Lastly, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was established to create and conduct multilateral trade agreements. Due to globalization, many portions of these institutions have undergone significant transformation. The IMF underwent a complete restructuring since the 2008 global financial crisis, the International Bank for Reconstruction was later transformed into the World Bank, and the GATT was later replaced by a much more robust World Trade Organization, which has a headquarters in Geneva that is growing by leaps and bounds.[19]

In the infrastructure ring, let us address one main impact of globalization in the technological sector. The entire Internet is designed around providing access, freedom of speech, and expression, as it was originally created by Vint Cerf, then a project manager at the U.S. Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), where he did the research that would earn him the title the “father of the Internet.” According to Cerf, “the Net already accounts for 13 percent of American business output, impacting every industry, from communications to cars, and restaurants to retail. Not since Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press or Alexander Graham Bell the telephone, has a human invention empowered so many and offered so much possibility for benefiting humankind.” [20] Overall, the globalizing effects of the Internet have exploded with the development of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn.

For an example of the effects of globalization in the population ring, one can point to the merging around the world of technological advancements, languages, and cultures. Since 1903, for example, the introduction of aviation has yielded a prime illustration of global merging. Aviation uses only one time zone for reference—Zulu time (or Greenwich Mean Time)—and one language – English. Almost one-fourth of the world’s population (more than 350 million native speakers and 400 million with English as a second language) can speak basic English and, even more profoundly, the number of spoken languages in the world has decreased by 48 percent from about 14,500 in 1500 to less than 7,000 in 2007.[21] Clearly, this represents global merging.

Globalization in the area of fielded forces has also evolved greatly over the last fifty years. One needs only look at the two World Wars, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), or the United Nations peacekeeping operations to understand this effect. There are basically two major international armament producers in the world, with a few more that produce for their own nations, but each company’s products look remarkably similar in form and function to the rest.

Warden’s theory of the Five Rings conceptually says that when one force or entity directly affects all other rings to an extent that, if it is crippled, it could seriously affect the function of the state, that force or entity forms the essential element of an additional ring. Since globalization has become such central element of the functioning of today’s state, a modernization of Warden’s rings warrants placing globalization as an independent, yet completely interdependent, sixth ring that one could attack (in the case of military strategic planning) or an entity which planners could build upon to improve a state (in the case presented in this paper). Clearly, building and incorporating globalization as a sixth ring would greatly contribute to the state-building process if planners could clearly identify where to best allocate resources and investments. In order to help identify the relative status of each state’s systems, we can look to several indicative metrics, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2: Six Rings for Analysis of the Modern State.

| Modern State | Forms of Indicative Metrics |

1. Leadership | Executive, state, parliament, judicial functions | Corruption index |

2. System Essentials | Economy and energy: electricity, oil, food, water, land | Human development index, water/food rights, global warming, GDP per capita |

3. Infrastructure | Sea lanes, roads, airfields, factories | Highways/roads, judicial system and the rule of law |

4. Population | People, human rights, freedoms, human security | Population, human development index |

5. Fielded Forces, Security Personnel | Military, police, firemen, intelligence services | Internal and external force structure, civil-military relations |

6. Globalization | Interaction with international organizations, travel, access, diversity | Market integration, UN participation, ICC-ICJ participation |

With definitions in hand, and a quick glance across the six rings, applying this lens to the entire world is still a daunting task. Perhaps a useful tool often found in political studies is to group states according to a specific set of criteria.

Six Rings in “Six Levels” of States

When one examines the 193 countries in the world, there is great disparity in the levels of all six rings with respect to global functioning and power. As Steger states, “Globalization is an uneven process, meaning that people living in various parts of the world are affected very differently by this gigantic transformation of social structures and cultural zones.” [22] Warden used an analytical tool when looking at different potential enemies with his Five Rings theory, using sequential Five Rings analysis at the next sub-level system inside each primary ring. Similarly, to assist with analyzing the potential development paths of the world discussed at the beginning of this paper, we can categorize the world into six different levels via a combination of multiple systems, such as global functioning and power. These “Six Levels” are similar, in part, to the nature of the First, Second, and Third World concepts that dominated the Cold War era. These are not strict lines of demarcation, merely just a “family resemblance” within each level. This ranking is similar to the floors on an elevator: the higher you go, the better the view. Extrapolating this concept creates a list resembling Table 3.

Table 3: Six Rings Applied to Six Levels of States in Global Functionality and Power.

| [193] Countries |

Level 6 | Ideal state: peace, prosperity, prime example to follow |

Level 5 | [1] United States |

Level 4 | [22] (G8) U.K., France, Germany, Canada, Italy, Russia, Japan, Brazil,India, China, South Africa, Australia, “Upper Europe” (aka Spain, Portugal, Benelux, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Switzerland) |

Level 3 | [44] G20/Next 11 Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia (G20), Iran, Mexico (G20), Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, South Korea (G20), Turkey (G20) and Vietnam. (rest of G20) Argentina, Saudi Arabia, + “Middle Europe” (aka Hungary, Austria, Poland, Ukraine), middle Americas, Asia, Africa |

Level 2 | [66] Lower “rest”: lower Europe, lower Americas, Asia, Africa |

Level 1 | [60] Failed, failing, collapsed states |

With this Six Level structure established, we can again apply Warden’s nested systems analysis, and examine one core ring as it applies to each of the six levels of states. As an example, let us look at system essentials, which includes economic and energy issues, and how these issues filter through the six levels of states.

Level One: Failed, Failing, and Collapsed States

There are several lists of failed or failing states; one example is the Foreign Policy “Failed State Index,” published annually since 2005. This list includes the sixty states that rank lowest on a combination of factors, including demographic pressures, refugees and displaced persons, group grievances, human flight issues, uneven development, economic decline, delegitimization of the state, public services, human rights, security apparatus, factionalized elites, and external intervention.[23] Each of these categories falls quite easily into one of the six rings of the model discussed above. Though the situation seems quite grim in Somalia, the Congo, and Sudan, numerous countries have improved their standing on the index over the last eight years. Few probably believed the United States “experiment” would survive in the late 1700s or early 1800s, but provided the right intervening foreign assistance, anything was possible. Simple investments in cell phone architectures have made drastic differences in newly forming countries, completely bypassing the developmental process through the telegraph, and even the telephone, straight to the Internet age.

Level Two: Lower “Rest”

The difference between the Level One and Level Two countries is the equivalent of the difference between sitting down and standing up. These states have at least a fledgling government that has proven able to provide for its citizens’ basic needs, and has started down the road of establishing a national economic basis. There is significant opportunity for growth, which often requires the investment of outside sources, particularly for security issues. These investments are happening all over the world at a rapid rate. Unfortunately, the global community is seemingly unable to agree on exactly how to best provide investments for these developing countries, and, according to the EU Trade Commissioner, the latest rounds of WTO investment standardization talks resulted in failure: “The Doha development round of trade talks initially started in 2001 with the aim of remedying inequality so that the developing world could benefit more from freer trade. However, the talks have repeatedly collapsed as developed countries failed to agree with developing nations on terms of access to each others’ markets.” [24] But there is hope, after all, that at least there is a global forum for the discussion of improving economic conditions in the developing world. Welcoming outside investment, building an infrastructure, and rapidly increasing GDP per capita are all similar to the developmental tendencies in the United States during the 1800–80 timeframe. Fortunately, however, no nation has to repeat the developmental process of the steam-powered train!

Level Three: G20, Next 11

The next level of state analysis consists of those countries that have building or semi-self-sufficient economies, are able to handle self-protection, but possess limited power to project their self-interests (the equivalent of walking, as an advance from sitting and standing in our example). This level of state might be considered the “middle class” nations of the world. Many would say, just as the middle class is the driving force within the U.S. economy, the Level Three countries are the driving force among states on the global stage. For instance, the significant push into developing Africa’s integration into the world economy has been driven by multiple donors, with diverse interests. For the U.S. and other Western nations, investment in Africa denies Al Qaeda a base of operations if there are thriving economies and representative governments. For China, India, and the rest of an ascendant Asia, the Level Three countries provide multiple sources of energy and natural resources to sustain the world’s largest populations.[25]

America’s military Central Command in Africa was started in May 2003, establishing the Combined Joint Task Force–Horn of Africa, and later AFRICOM. It effectively seeks to “build local capacity up, keep radical jihadists out, encourage Asia (and Middle Eastern) firms in, and [build] African militaries and governments, thereby bolstering continental peacekeeping. All can be accomplished on the basis of indigenous capacity first, regional cooperation second, and help from external great powers third.” [26] But perhaps Asia presents a better model for economic development in this region, as many Asian states understand how to handle millions of poverty-stricken people in a land with scarce natural resources. Barnett suggests, for example, that “Africa will be a knockoff of India, which is a knockoff of China, which is a knockoff of South Korea, which is a knockoff of Singapore, which is a knockoff of Japan, which half-a-century ago was a knockoff of the U.S.” [27] Whichever way you look at it, the nations in Level Three are in a substantial building phase. Many of these nations have similar developmental tendencies to the United States during the 1880–1930 timeframe.

Level Four: G8, Major EU and Asian Players

As we move to the next level of states, we consider a broad spectrum of global involvement and power development (“jogging” countries, to continue the metaphor). Countries at this level show self-sustaining economic and political development, are capable of some form of self-protection, and can implement some control over their self-interests abroad.

The economic power of the combined European Union (EU) can, when actually unified, propel it to an equivalent of the top level of nations, but it will likely be many years before the EU will have a coherent economic policy. European economic dominance is not new, however. Western European GDP per capita was higher than that of both China and India by 1500; and between 1350 and 1950, Western GDP per capita increased from USD 662 to USD 4,594, a 594 percent increase, while China and India remained relatively constant.[28] After World War Two, the reintegration and rebuilding of Germany and Japan helped create two of the largest powerhouses in today’s world economy. These two nations have also helped mold the economies of Europe and industrialized Asia along the way. The last thirty years, in addition, have seen an unprecedented wave of Asian economic development grow at a rate equivalent to the last two hundred years of Western growth. According to Alain Guidetti from the Geneva Center for Security Policy

The spectacular emergence of Asia is mainly led by the unprecedented development of the Chinese economy over the last 30 years (average growth of some 10 % until 2010, 8.5 % in 2012). China became the world’s second-largest economy in 2010, the world’s first trade exporter, and the major trade partner of the U.S. and Europe. This performance, while reflecting China’s new economic might, boosts its influence in world affairs, as illustrated by its ascent to the rank of third-largest member country of the IMF and its growing weight in the UN, the UN Security Council, as well as regional institutions such as ASEAN.[29]

Perhaps surprisingly, however, 61 percent of Chinese consumers are willing to pay more for a product labeled “Made in USA” over a foreign brand because of higher quality, particularly in baby food, household appliances, tires, car parts, furniture, and tools.[30] This highlights a grand interdependence between the Level Four and Level Five national economies. Clearly, globalization has many benefits for all involved.

Some of the nations that benefit most from rising Chinese trade include Australia, India, and Japan. Indian officials often claim that they are at a disadvantage to the Chinese because, as a senior government official states, “We have to do many things that are politically popular, but are foolish. They depress our long-term economic potential. But politicians need votes in the short term. China can take the long view. And while it doesn’t do everything right, it makes many decisions that are smart and far-sighted.” [31] An example of these limitations is that it took two years of attempts to open the Indian market to foreign investment. In December 2012, Manmohan Singh, the Indian Prime Minister, and his party pushed through economic reforms to allow foreign chains like Wal-Mart to operate in India. This move is likely to attract foreign investment to the ailing pension and insurance industries and the USD 450 billion retail sector.[32] Similarly, in the late 1980s, Japan’s automobile exports helped it develop into one of the top five economies in the world. Several analysts believed it would surpass the U.S. as the world’s largest economy, but the advent of significant Japanese competition and reforms caused U.S. auto producers to significantly improve their efficiency and quality. Japan’s markets, industries, institutions, and politics have made significant gains in the global market, but it has not surpassed the United States.[33] One could reflect that many of the Level Four nations are experiencing similar developmental issues as the United States during the 1950–90 timeframe.

Level Five: The United States

The fifth state level contains those states involved in every region of the world with dominant economic, military, and political power. In this level is the United States, although clearly even its power is not universal, as seen in the cases of Vietnam, and to some extent, the yet-to-be-resolved Global War on Terrorism. The U.S. economy, however, clearly has remained at the forefront of the world’s economic development, as a unique combination of technological advancements from the fur trade in the early nineteenth century through the Industrial Age combined with vast land and natural resources to vault it to soaring heights. Despite having only 5 percent of the world’s population, the U.S. accounts for a dominant share of the world’s economic output: 32 percent in 1913, 26 percent in 1960, 22 percent in 1980, 27 percent in 2000, and 26 percent in 2007.[34] According to the World Economic Forum, America’s ingenuity propels it to “first in innovation, university-industry collaboration, and research and development. China does not come within twenty countries of the United States in any of these, and India breaks the top ten on only two counts: market size and national savings rate. In virtually every sector that advanced industrialized countries participate in, U.S. firms lead the world in productivity and profits.” [35] Another two fields where the U.S. dominates are nanotechnology and biotechnology. There are more dedicated centers for nanotechnology research in the United States than in Germany, the U.K., and China combined, and U.S. biotech revenues approached USD 50 billion in 2005, five times greater than Europe, representing 76 percent of global revenues in the sector.[36] And, in fact, if examining all the top production sectors of the world, as represented in Table 4, the U.S. is at or near the top of each and every one, and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

The tremendous economic power of the U.S. is not only used for development, but also provides the largest budget for internal and external security of any nation in the world. After all, can you name another Department/Ministry of Defense that has seven geographic commands that cover all seven continents, or another Department of State (or Ministry of Foreign Affairs) that covers 250 posts in over 180 of the 193 countries in the world? [37] Economically speaking, Fareed Zakaria frames it best:

America has succeeded not because of the ingenuity of its government programs, but because of the vigor of its society. It has thrived because it has kept itself open to the world – to goods and services, to ideas and inventions, and above all, to people and cultures. This openness has allowed [the] U.S. to respond quickly and flexibly to new economic times, to manage change and diversity with remarkable ease, and to push forward the boundaries of individual freedom and autonomy. It has allowed America to create the first universal nation, a place where people from all over the world can work, mingle, mix, and share in a common dream and a common destiny. America’s great corporations access global markets, easy credit, new technologies, and high-quality labor at a low price.[38]

Table 4: Global Leaders of Development.[39]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Agriculture, food processing | U.S. | China | India | Brazil | Japan |

Pharmaceutics, biotechnologies | U.S. | U.K. | Germany | Japan | China |

Nanotechnologies, new materials | U.S. | Japan | Germany | China | U.K. |

Energy | U.S. | Germany | Japan | China | U.K. |

Defense and security | U.S. | Russia | China | Israel | U.K. |

Electronics, computers | U.S. | Japan | China | South Korea | Germany |

Software, information management | U.S. | India | China | Japan | Germany |

Automotive industry | Japan | U.S. | Germany | China | South Korea |

Aviation, rail transportation | U.S. | Japan | China | Germany | France |

The U.S. economic drive, however, does not proceed without consequence. The European preference for slow but steady development has long countered the “go-go” philosophy of the United States. Some would say this symbiosis in production has stalled progress, but, on the other hand, the combination of both has probably resulted in better rules and standards development along the way, possibly preventing extreme, self-serving goals and unsustainable consumption.[40] For example, the U.S. (along with parts of Europe) has become the leading consumer nation (by far) in the world over the last two decades. Overconsumption in the technology, banking, and retail consumer sectors set the conditions for the “Great Recession” of 2008, which quickly corrected the consumption trend. However, the economy is a balance, and for debt to exist, creditors must also exist. Sure enough, several nations from the developing world (many from Level Four) were willing to donate their newfound wealth to this vast consuming machine, piling up savings and then lending them to the Western world.[41] In the meantime, the potentially dangerous consequences of this economic imbalance led the Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff at the time, Admiral Michael Mullen, to assess in 2011 that “debt is the single biggest threat to [U.S.] national security and is basically not very complex math” – in effect, many would say the financial crisis has had the effect of delegitimizing America’s economic power.[42] The good news is, however, that there have been over fifty recessions in the global economy since 1920, and the U.S. has had significant trends of deficits followed by non-deficit spending. The final point for Level Five nations is they are always advancing—assembling lessons learned and moving forward, constantly evolving and refining their processes. The difference between Level Five and Level Four countries are not always great, and in fact, sometimes, nations exhibit characteristics of both levels simultaneously.

Level Six: The Ultimate State

This level can be described (like the highest level of social achievement), but it has not yet been achieved by any nation in the world. Perfect in every way, it refers to the ideal state that all nations would strive to become if possible. For instance, imagine if the United States could continue all the donations made by non-governmental organizations and relief agencies while designating significant military and economic aid to all countries of the world, participating in only UN sanctioned interventions, with an all-encompassing human rights commitment and adherence to the Geneva Conventions (including the CIA). Or, perhaps if China stays consistent with its message of “peaceful rise,” resolves its island disputes peacefully, and leaps forward to take measures to reduce all forms of pollution. Having a sixth level indicates that there is yet room for all states to rise in their development.

Though we only compared the developmental state levels inside one ring—that of system essentials, including the economy and energy sectors—clearly one could perform similar analyses within each of the six rings. Putting all these concepts together (Six Rings and Six Levels) provides us with a complete matrix with which we can analyze the development paths for the world, as depicted in Table 5.

The combined matrix of Six Rings and Six Levels now presents a complete lens through which to view the states of the world. Let us next turn to looking at the two main players of the next half-century and see how they look through this matrix lens.

What’s Next? Projection to 2050

The “Rise of All” is not evaluated simply on the basis of economic progress. It contains elements of development, sustainability, and learning lessons in all six rings of state interoperation. Before we examine these factors, let us look at how Zakaria’s research describes the “Rise of the Rest” with surprising twist:

Table 5: Six Rings and Six Levels Matrix for the Analysis of the Modern State.

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 G20, | Level 4 | Level 5 | Level 6 |

1. Leadership | Unstable, corrupt | Stable | Building | International interests | Advancing global agendas | 100 percent transparent |

2. System Essentials | Unavailable | Attainable | Readily available | Advancing | Efficient | Overflowing |

3. Infrastructure | Non-existent | Existing | Improving | Advanced | Leading-edge | Well developed |

4. Population | Suffering, disorganized | Basic needs met | Improving lot | Integrated | Educated, employed, advanced | Happy, human rights respected |

5. Fielded Forces, Security Personnel | Rebel groups | Basic internal | Internal + stand-alone military | Force projection | Multi-theater projection | Internationally effective |

6. Globalization | Disconnected | National | Regional | International | Global influence | Globally integrated |

The Rise of the Rest, while real, is a long process. And it is one that ensures America a vital, though different role. As China, India, Brazil, Russia, South Africa, and a host of smaller countries all do well in the years ahead, new points of tension will emerge among them. Many of these rising countries have historical animosities, border disputes, and contemporary quarrels with one another. In most cases, nationalism will grow along with economic and geopolitical stature. But these rivalries do give the U.S. the opportunity to play a large and constructive role at the center of the global order. It is a role that the U.S. – with its global interests and presence, complete portfolio of power, and diverse immigrant communities, could learn to play with great skill.[43]

Thus the key players are leaders in the Level Four through Level Six nations, predominantly the two global leaders: the United States and China. How they establish the pace of progress will determine what the rest of the world will do. Few counter the “Rise of the Rest” concept, so the real question is whether the United States will continue to rise or not, particularly in relative terms to China. In other words, can the U.S. also continue to advance with the rest of the world? In order to “Rise with the Rest,” the U.S. must continue to progress across all six rings.

The United States and the Six Rings

Ring 1: Leadership. When the U.S. first moved beyond the Monroe Doctrine of isolationism to involvement in “other nations’ affairs,” the other great powers noticed and were not quite certain what to make of an imperial power that did not want to colonize, but attempted to spread the rule of law and the doctrine of individual freedom.[44] By finally embracing global leadership in international security in the form of World War Two (although one could say the United States had it forced upon them by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor), then the Cold War effort at Soviet containment, the U.S. had to finally define “Americanism,” and along the way undergo significantly greater international scrutiny. As the world now watches globalization make similar demands on other societies, the U.S. must understand that political solutions take time. Fifty years after World War Two, the nations of Japan and Germany are world leaders in all aspects. One must exercise patience with the nations of Iraq and Afghanistan. To advance in the Leadership Ring, the U.S. should ratify and fully vest in the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice concepts, and must learn to patiently work towards developing coalition-style political solutions to long-term economic problems.[45] Though individual leaders will change, the system of checks and balances ensures that the system shall prevail. More importantly, the U.S. is less reliant on the skills of a particular leader, and is thus more likely to continue to progress as a continuously evolving system of leadership.

Ring 2: System Essentials—Economy and Energy. Simply mention Wal-Mart, Starbucks, McDonalds, Stanley Tools, Chevrolet, or Ford, and most nations across the world will recognize one of the names. By far, the largest trans-national companies in the world today are based in the U.S. The rules of globalization are not necessarily just American, but U.S. domestic and foreign policy do have a great effect on a global level.[46] To advance in the systems essentials ring, the U.S. must continue to articulate and execute its national strategy at the WTO, G8, and G20 forums on global economic development. The U.S. must:

· Maintain a focus on improving new regulatory oversight of inter-market financial flows

· Invest energy into the exploration, production, and protection of new energy reserves

· Adjust to retail, food, and production pattern changes (like job outsourcing on the low-end).

Additionally, the U.S. introduction of shale gas generated through hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”) will increase production and economic advancement. U.S. natural gas output has soared in the last decade, as well as the introduction of biofuels, causing a resurgence of corn production across the U.S. Midwest. Not only has the increase of output from inside the U.S. in terms of oil and gas production bolstered the United States’ position relative to other nations, but new technologies have led to an increase in reserves and a lack of reliance on outside sources that assists with strategic security as well. The International Energy Association even suggested the U.S. may surpass Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer within the next decade.[47] Recessions are ruthless at creating efficiencies, and the recent global recession caused U.S. manufacturing production costs to drop rapidly. As a result, many producers are returning their production facilities to the United States after having moved them abroad. The Federal Reserve announced in April 2013 that they will consider a plan to start raising federal interest rates. This, combined with the fact that the Dow Jones Industrial Average is at an all time high and many other signs, all suggest that a U.S. economic recovery is imminent.[48]

Ring 3: Infrastructure. Thomas Barnett states, “America arose as a global power thanks to its ability to knit together its states: interstate trade integration through the disintegration and geographic distribution of production chains, with transportation infrastructure—sometimes literally—paving the way for national firms with national platforms that peddle internationally branded products.” [49] To advance, the U.S. must continue to:

· Develop its aging highway system

· Invest in transnational transportation methods that are both secure and efficient

· Continue to serve as the guarantor of worldwide security of seaborne commercial traffic

· Lead development on the next edition of the Millennium goals

· Ratify the Kyoto Protocol, and continue working toward the next effort to curb global warming – an effect that will stress Level One and Two nations the most.[50]

Ring 4: Population. Higher education is the United States’ best industry. Of the top twenty universities in the world, at least fifteen are in the U.S.; of the top fifty, between twenty-seven and thirty-seven. The U.S. invests 2.6 percent of its GDP in higher education, compared with 1.2 percent in Europe, and 1.1 percent in Japan. In India, universities graduate between thirty-five and fifty Ph.D.s in computer science per year, while the U.S. produces one thousand.[51] Second, the U.S. will increase its population by 65 million by 2040, while Europe will remain virtually stagnant. The United States’ edge in innovation is overwhelmingly a product of immigration; foreign students and immigrants account for 50 percent of the scientific researchers in the U.S. The United States’ potential new burst of productivity, its edge in nanotechnology, biotechnology, and its ability to invent the future – all rest on its immigration policies (which are the cause of heated debate in U.S. domestic politics).[52] For the U.S. to advance, it must focus on ways to improve its primary and secondary education systems to be the best in the world, particularly in science and technology; develop simpler immigration and taxation laws; and continue to work on the spread, prevention, and inoculation against communicable diseases, particularly in Africa.

Ring 5: Fielded Forces. The U.S. is by far the largest military power in the world, but the last two decades have proven that the only way for the U.S. to deter aggressors is to build broad, multi-national coalitions.[53] The new U.S. strategy issued in 2012 mentions strengthening existing bilateral military alliances (Europe, Middle East, Japan, Republic of Korea, Australia, Philippines, Thailand) and developing strategic security partnerships with other Asian players, in particular India, Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia. The other elements of this strategy include a renewed commitment to cooperate with China, a new focus on regional multilateralism, and the promotion of trade and democracy.[54] To stay in the lead in the realm of security, the U.S. needs to:

· Reduce force sizes and budgets to a sustainable level that reduce the debt to controllable levels

· Work toward a reunification or lasting peace process between North Korea and the Republic of Korea, with the assistance of key regional players

· Increase military-to-military cooperation with China, India, Russia, and Brazil, and the “Next Eleven”

· Encourage any regional security cooperation structures throughout the world

· In the cases of Central Command (Middle East and Central Asia), Southern Command (Latin America), and the new Africa Command, continue to invest in the security of the Level One and Two nations

· Continue to invest in border security while protecting the process of lawful immigration.

Ring 6: Globalization. The United States did not invent globalization, but it did perfect it. There is no question that the U.S. dominates the globalization spectrum, particularly in the technological sector. However, many feel that in the last decade and a half, America’s international aggressiveness has caused negative feelings to erode some of this globalization effect. The economic ties between the different markets of the world and the United States during the 2008 global economic crisis showed clearly what nations are completely globalized and what nations are still insulated. There is little doubt, however, that the U.S. will continue to lead in, and enjoy the effects of, the processes of globalization, particularly in its relations with China.

China and the Six Rings

With the opening of China’s markets in the 1970s, the era of economic cooperation between East and West began in earnest. The China-U.S. economic relationship is one of symbiosis. The U.S. and Western Europe are vast spenders, with a seemingly insatiable appetite for inexpensive goods, and the Chinese economy, with the world’s largest pool of unskilled workers, is quite happy to produce them.[55] On the other hand, however, a serious U.S.-China rivalry could define the new age and turn it away from integration, trade, and globalization.[56] The Chinese have advertised a policy of peaceful advancement, and have shown a willingness to join regional developmental organizations and to display (relatively) restrained involvement in international organizations such as the UN, all while working as the symbiotic “good cop” of the world with the U.S.[57] We can now examine how the rise of China also extends across all Six Rings.

Ring 1: Leadership. The Chinese Communist Party spends an enormous amount of time and energy worrying about social stability and popular unrest, in particular about the possibility (already borne out elsewhere in the world) that economic development leads to political reform.[58] According to Zakaria, “The rule has held everywhere from Spain and Greece to South Korea, Taiwan and Mexico: countries that modernize begin changing politically around the time that they achieve middle-income status (a rough categorization, that lies somewhere between $ 5,000 and $ 10,000 PPP).” [59] China’s per capita income stands well below that range, and will not reach it for another two decades or more, so the jury is still out on what changes the new government will adopt, though it appears the regime has learned from the lessons of the pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989 in Tiananmen Square, and seems willing to adapt.[60] In the judicial realm, for example, in 1980, Chinese courts accepted 800,000 cases; in 2006 they accepted ten times that number.[61] As China develops, its leadership will have to deal with adapting to the nation’s newly elevated status without doing so at the expense of the Chinese people.

Ring 2: System Essentials—Economy & Energy. China’s economy increasingly mirrors that of the U.S. Originally, China encouraged big business development, rising from the private sector or state-owned entities, and mostly funded by state-controlled banks. Only recently are small-businesses growing via investment funds from foreign sources.[62] China also has the advantage of knowing they own the global market on low-end manufacturing, while the United States owns the high-end sector. Resource scarcity, disappearing habitable land, acid rain, and polluted environments are all massive issues that China must deal with while trying to modernize. According to Pan Yue, China’s Deputy Minister of the Environment,

Acid rain is falling on one third of the Chinese territory; half of the water in our seven largest rivers is completely useless, while one-fourth of our citizens do not have access to clean drinking water. One-third of the urban population is breathing polluted air, and less than 20 percent of the trash in cities is treated and processed in an environmentally sustainable manner. In Beijing alone, 70 to 80 percent of all deadly cancer cases are related to the environment. [But] in some cities such as Beijing, the air quality has, in fact, improved. The water in some rivers and lakes is now cleaner than it’s been in the past. It’s the assumption that the economic growth will give us the financial resources to cope with the crises surrounding the environment, raw materials, and population growth.[63]

With their rapidly increasing issues of population growth and resource scarcity, magnified by the massive population of their nation, Chinese leaders have to get the system essentials correct.[64]

Ring 3: Infrastructure. China expert Elizabeth Economy argues, “A century ago, the U.S. was grappling with many of the same problems that currently confront China: rapid deforestation in the Midwestern states, water scarcity in the West, soil erosion and dust storms in the nation’s heartland, and loss of fish and wildlife.” [65] Minxin Pei points out “the automobile fatality rate [in China] has increased to twenty-six per 10,000 vehicles (compared with twenty in India and eight in Indonesia), but the [number of] cars on China’s roads have been growing by 26 percent per year, compared with 17 percent for India and 6 percent for Indonesia.” [66] In effect, many of the problems that China is facing now are similar to what the United States faced with its massive expansion in the highway system and nationwide industrialization in the first sixty years of the twentieth century. They have a significant eastern seaboard development, with sparse population (but most of the nation’s resources in the west). China will have to achieve significant infrastructure improvements to continue to handle the advancing needs of Chinese society.

Ring 4: Population. John Thornton, writing in Foreign Affairs, has painted a picture of a Chinese governmental regime hesitantly and incrementally moving toward greater accountability and openness.[67] Almost weekly, there are reports of protests, particularly around environmental issues, taking place in China, and most are not dealt with harshly. In a surprising statistic, in 1994, there were just 10,000 protests of some kind or other in China, while in 2004 there were 74,000.[68] It appears that the government is not only hearing the voices of the people, but also recognizing their complaints and adjusting their behavior.

Ring 5. Fielded Forces. After two decades of double-digit military growth, China now has the world’s second-highest military budget (USD 108 billion in 2012, accounting for 2 percent of GDP), well ahead of Japan, Russia, and India.[69] Though it advocates peaceful relations, China has recently become a more overt actor in international relations. In December 2012, for example, China demanded that Vietnam stop its activities in disputed waters and not harass Chinese fishing boats. Similarly, China has recently found itself in increasingly angry disputes with its neighbors, including the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and Japan over claims to islands and parts of the South China Sea.[70] Whether they are rising peacefully or to counter other states’ military actions will have a significant effect on the future of relations in the region and the world.

Ring 6: Globalization. In terms of its economic advances, China has taken twenty-five years to achieve what took the United States over two hundred years. Turning around a moribund economy into the world’s second-largest was not a small feat. The amount of goods and travel that go through Shanghai and Beijing was clearly evidenced during the 2008 Olympics, but there were still definite restrictions on showing only the events that China had a likelihood of winning throughout the homeland. China continues to limit its population’s access to a free press and free Internet, and enacts basic censorship controls. Some also accuse China of keeping exchange rates artificially low despite owning significant cash reserves in the currencies of other countries, particularly the U.S. The continued rise in global markets will only increase the pace of China’s globalization and integration, bringing with it a higher likelihood of continued peaceful relations. There are several theorists, for example, who suggest that globalization is making the world more integrated and will continue to bring about more peaceful relations. The theory is that if the economies of two countries are globally intertwined and linked (like the trade balance between China and the U.S.), they are more likely to negotiate toward peaceful solutions, and less likely to lean toward hostile relations. The “soft power” of globalization can then, theoretically, help make the world a more peaceful place as we proceed through the next half-century.

Conclusion: The “Rise of All” as We Move Toward 2050

Now that we have developed the Six Rings concept, examined how the System Essentials ring crosses all Six Levels of states, and looked at how the two main players on the international stage are affected in each ring, let us examine how the future of international relations might look as we move toward 2050. A December 2012 report from the National Intelligence Council predicts many shifts in the international spectrum, which they summarize as follows:

In the world today, people are increasingly realizing that the successful development of countries is possible only through the augmentation of joint efforts for solving global problems. This trend counteracts growing radicalism of marginal regimes and different socio-political, religious and ethnic groups. Over the next 20 years, the world will develop in an evolutionary manner without the radical changes and upheavals that were characteristic of the preceding two decades.[71]

In the United States, this report has sparked extensive discussion among governmental agencies on how to modernize and remain at the forefront of the world well beyond the next twenty years. The hope is that fewer radical changes and upheavals (in comparison with the past twenty years) will allow different resource allocations and personnel adjustments for both the Department of Defense and the Department of State. Since 1990, the U.S. military has had a significant footprint in the Middle East, which it looks to draw down significantly within the next five years. For other regions, however, the U.S. seems plenty willing to continue in its role as the international muscle in the security realm. These massive military draw-downs in the Middle East will allow for a renewed focus on other international issues. And, in fact, the “Pivot to Asia” declared by the Obama Administration is really just a rebalancing of resources to return to the pre-1990 status of a more even distribution between the Atlantic and Pacific theaters.

In the eastern theater, the U.S. will have more time and resources to focus on developing economies beyond the G20 nations without having to focus on Cold War containment, or massive resource-intensive conflicts in the war on terrorism. The extra time and resources will also allow for a more concentrated focus on the pre-9/11 efforts of conflict resolution on the Korean Peninsula. With the assistance of China’s support in the region, perhaps all parties could resume the six-party talks that have stalled since before 2009, only with an added emphasis on either a permanent peace agreement or a reunification plan. Ideally, the icing on the cake would be a serious conversation about the sustainability of the status of Taiwan, and possibly developing a Sino-U.S. agreement for the long-term stability of the Taiwan Straits.[72] We have already discussed the fact that the massive surge in Chinese markets stemmed from a willingness to permit a degree of economic freedom in the 1970s. Even though this occurred with a high amount of state involvement in the development of specific sectors and infrastructure, it is relatively concrete proof that any country could follow similar steps. Logically, then, one could extrapolate that a focus on a globally integrated economy now could improve the interrelations of all nations over the next fifty years.

In the European theater, the U.S. will need to improve and reinforce relations with the EU. Within the economic realm, one can look at the merging of U.S., Canada and Mexico’s interests in the 1993 North American Free Trade Agreement. Between 1993 and 2006, NAFTA trade increased 197 percent, with U.S. exports to its NAFTA partners increasing by 157 percent, as opposed to a 108 percent increase in trade with the other nations of the world. An EU/NAFTA free trade agreement could have a similar effect. By all accounts, this could significantly enhance over 50 percent of the global trade market and, furthermore, considerably increase the integration of the global economy.[73] The European Union is arguably the world’s largest “peaceful experiment” in progress, including winning the Nobel Prize for achievements towards the end of war in Europe. However, the Schengen Zone is quickly discovering the effects of immigration that affect many other areas of the world. Many would say, however, that this is not a bad thing, and that its multi-ethnic diversity has been the engine of the United States’ economic improvements over the last decade.

In the remainder of the Western hemisphere, the growing powers of Brazil and Mexico are influencing their nearby neighbors. We have seen significant phase shifts in the opening of Cuba to businesses, and a display of recent accounting shortages in Venezuela, and potentially even a negotiated settlement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia (FARC). Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina are having profound developing influences on the rest of the states in their neighborhoods. The likely forecast is continued improvement and definite rise in these states.

In the Middle East, the Arab Spring has introduced some of the most significant changes of any period in recent history. As many of these fledgling governments establish their course for the future, they are ripe for political and economic investments and are searching for good examples of how to contribute to the international community. Instead of spending USD 200 billion per year on the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, the U.S. can now allocate more resources to the Department of State and follow a leadership path that is much more transformational versus transactional, maybe even proposing a new round of peaceful negotiations to address the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In the African context, we have addressed the impact of U.S. AFRICOM and Chinese investments. Modern societal advancements are making their way each and every day to the numerous Level One and Two countries on the continent, and the fledgling African Union is integrating the five regional intra-governmental structures on the continent in unprecedented ways.

Across all six levels and all six rings, evidence supports the theory that the world could continue to advance, albeit slowly, one step at a time. In global governance, there has been a significant trend towards democratization and greater respect for individual rights. The number of conflicts and intra-state wars has declined to the lowest numbers in world history, although thanks to global media coverage, these conflicts may seem to be more graphic of late. The same forces have highlighted a trend of corruption in developing nations, but these same transparency forces are causing the “corruption index” to have a great effect, and the dichotomy of the rich getting richer and controlling all of the corrupt nations (i.e., aristocrats) is at least exposed to public awareness, if not placed on the road to elimination. Take, for example, recent attention paid to bribes in the Afghan government, and the influence that has had on the Karzai regime. And, on global issues such as energy consumption and science advancement, the world has made (and will likely continue to make) significant progress. In a “Future of Energy” study conducted by the Shell Corporation, they predict that:

By 2050, over 60 percent of electricity comes from renewable resources. Carbon capture/storage means fossil fuels are used in more environmentally friendly ways. The world [will] need around 26 percent less energy than if it had not acted. Though energy use will be much higher than it is now, it is far lower than it could have been and the path is much more sustainable. There will be three billion more of us, but CO2 emissions will be lower per capita.[74]

Thus, it appears in each of the six rings, there is clear evidence of likely improvement in the future. Though the “Rise of All” could describe the course the world takes between now and 2050, it is certainly difficult to prove that this is the one and only answer, as there is really no historical precedent for the simultaneous advancement of all nations in the world (just as the Unipolar World, the Multipolar World, or the “Rise of the Rest” also likely provide incomplete explanations). Trying to extrapolate from other venues, however, one can see logical scenarios where integrated development and competition has advanced all players. In the field of Olympic sports, for instance, there is clearly increased competition between all nations, but the Olympics also provide a forum where nations can get along more harmoniously than anywhere else. A particular example came when South Korean and North Korean athletes marched out under the same flag during the 2000 Sydney Olympics, a level of cooperation not achieved in the political realm in over sixty years. And yet, simultaneously, intense Olympic competition has led to new world records year after year. One can find another example in the power grids of the United States. The high level of interconnectedness means that there are fewer grand failures; when one power station fails, the rest of the grid picks up the load, and customers continue to enjoy power. Only a massive systemic shock can cut power to the entire grid. And, in a final example, when a family of three children all enjoy participating in track and field, and the third child starts to get really fast, the older siblings tend to improve their own performance in an attempt to remain ahead of their younger challenger.

In that vein, if Europe’s global dominance has come and gone, and the U.S. is now maximizing its performance on the “athletic field,” perhaps China—the third sibling in this scenario—will end up performing faster and better. But clearly, in this case, China’s performance will entice the other two “siblings” to adjust their performance to match. And so, between now and 2050, the three actors will only continue to improve as the other 190 siblings around the world decide to pick up the sport, and bring about the “Rise of All.”

* Colonel James Thompson is a US Air Force pilot that has commanded two different squadrons and flown F-16, F-117, MC-12, and MQ-9 aircraft in combat. He has Masters degrees in Aerospace Engineering, Leadership, and Counseling and is a US Air Force Academy and US Air Force Weapons School graduate. Most recently, he served as a US Defense Fellow at the Geneva Center for Security Studies in Geneva, Switzerland, and graduated from the US Air War College in Maxwell, AL.

[1] “TIROS,” NASA.gov; available at http://science.nasa.gov/missions/tiros/. The Sputnik and Explorer 1 satellites were launched prior to TIROS, but were not self-sustaining, and both ran out of power in less than four months.

[2] Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs 70 (1990–91): 1

[3] Giovanni Grevi, “The Interpolar World: A New Scenario,” EU Institute for Security Studies Occasional Papers, no. 79 (June 2009), 44.

[4] Dani Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox, Democracy and the Future of the World Economy (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), xix.

[5] Ian Bremmer, “Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World,” South China Morning Post (25 March 2012), 15.

[6] Fareed Zakaria, The Post American World (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2012), 285.

[7] John Warden, “Air Theory for the Twenty-First Century,” Airpower Journal (September 1995); available at http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/battle/chp4.htm

[8] Warden, “Air Theory for the Twenty-First Century,” 3.

[9] Howard Belote, “Warden and the Air Corps Tactical School: What Goes Around Comes Around,” Airpower Journal (Fall 1999); available at http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/apj/apj99/fal99/belote.html.

[10] Warden, “Air Theory for the Twenty-First Century,” 2.

[11] Belote, “Warden and the Air Corps Tactical School,” 3.

[12] Warden, “Air Theory for the Twenty-First Century,” 6.

[13] Manfred Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 8.

[14] Ibid., 103.

[15] Ibid., 59.

[16] Ibid., 58.

[17] Ibid., 69.

[18] Thomas P. M. Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush (New York, NY: Berkley Books, 2010), 294.

[19] Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, 39.

[20] Vinton Cerf, “‘Father of the Internet’: Why We Must Fight for its Freedom,” CNN.com (30 November 2012); available at http://edition.cnn.com/2012/11/29/business/opinion-cerf-google-internet-freedom.

[21] Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, 81.

[22] Steger, Globalization. A Very Short Introduction, 11.

[23] “Failed States Index 2012,” Foreign Policy; available at http://www.foreignpolicy.com/failed_States_index_2012_interactive.

[24] “World Trade Talks End in Collapse,” BBC News (29 July 2008); available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7531099.stm.

[25] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 286.

[26] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 286.

[27] Ibid., 248.

[28] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 66.

[29] Alain Guidetti, “Reshaping the Security Order in Asia-Pacific,” Geneva Centre for Security Policy Paper 2012/11 (2012), 1; available at www.gcsp.ch/Regional-Capacity-Development/Publications/GCSP-Publications/Policy-Papers/Reshaping-the-Security-Order-in-Asia-Pacific.

[30] Nick Zieminski, “‘Made in USA’ Label Popular in China, too: Study,” Reuters (14 November 2012); available at http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/15/us-china-usa-consumers-idUSBRE8AE00520121115.

[31] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 108.

[32] Nigam Prusty, “Indian Government Wins Vote on Wal-Mart-type Stores,” Reuters (6 December 2012); available at http://news.msn.com/world/indian-government-wins-vote-on-wal-mart-type-stores.

[33] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 22.

[34] Ibid., 197.

[35] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 200.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of State, “Diplomacy: The U.S. Department of State at Work” (June 2008); available at www.state.gov/documents/organization/46839.pdf.

[38] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 283.

[39] Andrei Zagorski, “Economic Cooperation in the Post Soviet Space,” presentation at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, Geneva, 4 March 2013.

[40] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 211.

[41] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 47.

[42] “Mullen Talks About Deficit, Santorum Outlines Foreign Policy Position,” C-Span (28 April 2011); available at www.c-span.org/Events/Mullen-Talks-About-Deficit-Santorum-Outlines-Foreign-Policy-Position/10737421203/.

[43] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 257.

[44] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 112.

[45] Ibid., 127.

[46] Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, 106.

[47] Peg Mackey, “U.S. to Overtake Saudi as Top Oil Producer: IEA,” Reuters (12 November 2012); available at www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/12/us-iea-oil-report-idUSBRE8AB0IQ20121112.

[48] U.S. Federal Reserve Press Release 1 May 2013; available at www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130501a.htm.

[49] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 162.

[50] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 249.

[51] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 207.

[52] Ibid., 215.

[53] Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, 106.

[54] Guidetti, “Reshaping the Security Order in Asia-Pacific,” 2.

[55] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 140.

[56] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 141.

[57] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 234.

[58] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 113.

[59] Ibid., 114.

[60] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 177.

[61] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 114.

[62] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 175.

[63] Aus dem Spiegel, “The Chinese Miracle Will End Soon,” Der Spiegel (10 August 2005); available at http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/spiegel-interview-with-china-s-deputy-minister-of-the-environment-the-chinese-miracle-will-end-soon-a-345694.html.

[64] Barnett, Great Powers, America and the World After Bush, 186.

[65] Ibid., 383.

[66] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 113.

[67] John Thornton, “Long Time Coming: The Prospects for Democracy in China,” Foreign Affairs 87 (2008): 15.

[68] Zakaria, The Post-American World, 110.

[69] Guidetti, “Reshaping the Security Order in Asia-Pacific,” 1.

[70] “Rare Protests in Vietnam against China over Sea Disputes,” Reuters (9 December 2012); available at http://news.msn.com/world/rare-protests-in-vietnam-against-china-over-sea-disputes-2.

[71] National Intelligence Council, “Strategic Global Forecast to the Year 2030,” International Affairs 57 (2012).

[72] Guidetti, “Reshaping the Security Order in Asia-Pacific,” 4.

[73] “NAFTA’s Winners and Losers,” Investopedia (26 February 2009); available at www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/north-american-free-trade-agreement.asp#ixzz2IWY11mza.

[74] Shell Global, “Shell Energy Scenarios to 2050,” available at www.shell.com/global/future-energy/scenarios/2050/acc-version-flash/2050.html.

- 57120 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML