Xinjiang in China’s Foreign Policy toward Central Asia

Publication Type:

Journal ArticleSource:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 12, Issue 3, p.87-108 (2013)About the author*

Introduction

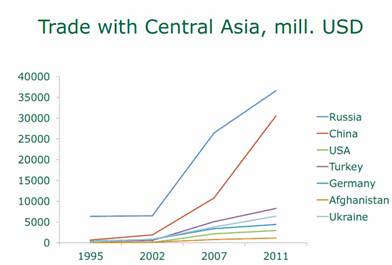

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to the appearance of new players in the Central Asian region, the most important of which is China. In the span of some twenty years, China has become a major trade partner and investor in the region. Its trade with nations in the region has grown impressively, from almost nothing in 1991 to more than USD 30 billion in 2011, with China being the region’s second-largest trading partner after Russia. According to the Premier of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Wen Jiabao, Chinese direct investments in Central Asia by 2012 are estimated at USD 250 billion.[1] China is extensively building oil and gas pipelines, developing a network of transportation links, “as well as expanding its diplomatic and cultural presence in the region.” [2]

Scholars and experts on the region have devoted extensive attention to the question of what are the drivers of Chinese policies in Central Asia. There is a consensus among Western as well as Chinese and Central Asian researchers that the region is not the primary focus of China’s foreign policy. China’s relations with the United States is its most important bilateral relationship, and perhaps the primary focus of its foreign policy, along with relations with Japan and other nations in North East Asia, with concerns over stability on the Korean Peninsula taking second place. South East Asia and the wider Asia-Pacific region take third place in order of priority.[3] However, one point that has been highlighted by most studies is that the aspiration to pacify the restive northwestern region of Xinjiang (officially the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region) constitutes the key factor that defines Chinese engagement with and presence in Central Asia.[4] Thus, according to Sébastien Peyrouse, “If Chinese influence in Central Asia has evolved in the course of the two post-Soviet decades, China’s key interests have not changed. The Central Asian zone has strategic value in Beijing’s eyes owing to its relationship with Xinjiang.” [5]

Huasheng Zhao, writing in 2007, argued that China’s economic interests in Central Asia are insignificant in terms of explaining Chinese interest in the region, while its role in guaranteeing the stability and economic development of Xinjiang and thus the territorial integrity of China is essential.[6] Furthermore, he says that the logic behind the Chinese presence in Central Asia is inherently led by domestic pressures, particularly with regard to security needs.[7] Prominent Kazakhstani sinologist Konstantin Syroyezhkin says that Central Asia is seen by China as a “strategic rear,” since the problems that take place in the region have significant impact on one of China’s Achilles’ heels: Xinjiang.[8] As Stephen Blank emphasizes:

Xinjiang, like Taiwan and neighboring Tibet, is a neuralgic issue for China, which desperately needs internal stability in that predominantly Muslim, resource-rich and strategically important region. Beijing’s strategic and energy objectives are based on stability in Xinjiang, and its Central Asian policies grow out of its preoccupation with stability there.[9]

Although a study of the centuries-long historical, cultural, and ethnic ties between Central Asia and Xinjiang is of interest in itself,[10] the emphasis that China places on Xinjiang with regard to its policy in Central Asia is a significant topic of study, as it highlights a number of characteristics and concerns of contemporary Chinese strategic thinking and strategic culture. China’s promotion of the idea of the “three evils” identified by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)—terrorism, extremism, and separatism—gives insights into China’s priorities in the region.

This article is an exploration of the place of Xinjiang in China’s foreign policy toward Central Asia. It does not ask the question of what are China’s overall interests in Central Asia, and does not doubt that there are multiple Chinese interests in this region over and above its concerns with stability in Xinjiang. Instead, it turns the question around: What is the place of Xinjiang in China’s policy in Central Asia? Is China’s engagement with Central Asia mediated in any way by its domestic policies and concerns over Xinjiang? To restate the focus, the article is interested in finding out any and all relevant roles and factors that Xinjiang represents for China in Central Asia. Furthermore, by doing so the study goes to examine the transformation of Chinese priorities and tactics towards Central Asia as well as to explore the way in which China has expanded its influence in the region. Thus, China in this paper is examined as an object, Central Asia as a subject, and Xinjiang as a factor.

The essay is also impelled by a number of other facts, such as the rapid development of Xinjiang in recent years, and the share of Central Asian states in Xinjiang’s foreign trade volume, accounting to some sources for approximately 83 percent, and being the region’s biggest trade partner.[11] Moreover, about 80 percent of China’s trade with Central Asia is conducted through Xinjiang.[12] However, it is important to note that this paper does not see Xinjiang as an autonomous actor, but as a factor of Chinese policy in Central Asia.

Xinjiang represents the only border China shares with Central Asia: more than 1,700 km with Kazakhstan, approximately 1,000 km with Kyrgyzstan, and about 450 km with Tajikistan.[13] Moreover, Xinjiang is closely linked to Central Asia by historical, cultural, religious, and ethnic ties.

The clashes between ethnic Uighur and Han Chinese in Urumqi in 2009, which allegedly resulted in over 200 deaths, arguably represented China’s most significant ethnic unrest in decades.[14] China’s concern over Uighur ethnic separatism in Xinjiang has pushed it to increase the pace of development in what is its largest region, yet remains one of its poorest. China’s aspirations of “leapfrog development” and “long-term stability” in Xinjiang are likely to result in respective “leapfrog” increases of Chinese presence in Central Asia.[15] And it is beyond any doubt that this development is already taking place.[16]

Drawing from the main arguments made in the literature on Chinese influence in Central Asia, this article poses and aims to test three sets of hypotheses. The first hypothesis posed is: “Chinese foreign policy in Central Asia is an extension of its policy over Xinjiang.” This hypothesis claims that for Beijing, having cooperative regimes in Central Asia provides insurance that Xinjiang separatism will not be supported by these countries. Furthermore, the stronger the economic ties between Central Asia and China/ Xinjiang, the less rosy are the prospects for political/ethnic separatist movements.

A second hypothesis, competing with the first, is: “Xinjiang’s place in Chinese foreign policy toward Central Asia is purely pragmatic and economic; the development of the previously laggard Xinjiang region is a goal with no relation to separatism.” Sub-hypotheses are: “As one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, China pursues every market it can get, no matter how small or big.” Another: “Economic development of Xinjiang is in the overall development interests of China.”

A third hypothesis is: “Xinjiang is an element of Chinese foreign policy toward Central Asia as a great/major power.” Sub-hypotheses here can be stated as: “Xinjiang is the western frontier of China, bordering Central Asia, and its role is only that of such a bordering region” and “A pro-Chinese Central Asia is a way to prevent U.S. encirclement.” Another sub-hypothesis: “Chinese policy in Central Asia is comparable to Chinese policy in East and Southeast Asia – a strategy of gradual economic-based rise into major-power status and dominance.” Here it would be potentially interesting to test the following sub-hypothesis: “If China’s ‘key’ to enter Southeast Asia was the Chinese ethnic and cultural presence there, the Turkic Uighurs of Xinjiang are a key to enter/link up with Central Asia.”

To summarize, the first main hypothesis might claim that Xinjiang is a significant separatist concern for China, and therefore its Central Asian policy is designed to address and manage that threat. The second main hypothesis claims that Xinjiang was poor (and therefore also separatist), so China’s strategy to develop Xinjiang was through trade and economic integration with Central Asia. The third main hypothesis is that Xinjiang is an element of China’s great-power strategy, and that Xinjiang’s Uighurs may serve as a useful link to Central Asia. The article will elaborate and test each of these assumptions, and see whether any of these hypotheses are able to provide helpful insights about Xinjiang and its relationship to China’s policy in Central Asia.[17]

This inquiry is relevant given the growing interest in the “Chinese Rise” around the world, as well as in academia. It will further analyze the topic of the often-neglected Central Asian aspect of this “Rise.” As Niklas Swanström notes, “The implications of the growing Chinese prominence in the region will undoubtedly have a significance that extends beyond the region, and to fully grasp the potential (or threat) of this, it is crucial to understand Chinese intentions and the extent of its influence.” [18] While it is true that a significant portion of the scholarship on Central Asia is devoted to studies of the growing role of China in the region, this article offers a new perspective for framing Chinese policies towards Central Asia through the lens of policies in Xinjiang.

Xinjiang and Central Asia: Elevating the Internal, Linking to the External

The following sections of this article are aimed at testing the validity of the three hypotheses posed above against the empirical realities of Chinese policies in Central Asia. This section aims at testing the first hypothesis, which assumed: “Chinese foreign policy in Central Asia is an extension of its policy over Xinjiang.” This hypothesis claims that for Beijing, having cooperative regimes in Central Asia provides insurance that Xinjiang separatist movements will not meet with support in these countries. Furthermore, it assumes that the stronger the economic ties between Central Asia and China/Xinjiang, the lower the chances for political/ethnic separatist movements. This section seeks to demonstrate how China addressed the very realist goals of maintaining national security, territorial integrity in Xinjiang, and stability in Central Asia through the liberal means of economic expansion, regional integration, and development promotion.

Realist Needs

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, China found itself in a situation where it had to engage with a number of independent states to its west, instead of one Soviet superpower. Relief from the Soviet threat was soon replaced by the uncertain prospects of managing relations with the unstable and largely unknown region of Central Asia to its west, as well as the threat of regional Islamic and Pan-Turkic revival in terms of its possible spillover into separatist Xinjiang. The dissolution of the Soviet Union coincided with the wave of unrest in Xinjiang in 1990–91, including an Islamist-inspired rebellion in the township of Baden.[19] The level of threat perceived in Beijing due to the convergence of external and internal factors “was illustrated by Vice-Premier Wang Zhen’s exhortation during a visit to the provincial capital of Urumqi for the regional authorities to construct a ‘great wall of steel’ to defend the motherland from ‘hostile external forces’ and ‘national splittists’ internally.” [20] Not surprisingly, the primary (if not the only) objective of Beijing’s policies in Central Asia throughout the 1990s was to guarantee stability in the northwest by dealing with the border issues and trying to ensure that the newly established governments recognized and respected the “One China” discourse and controlled separatist elements within the Uighur diasporic community in the region. Xing Guangcheng argued that, “to a larger extent the stability and prosperity of Northwest China is closely bound up with the stability and prosperity in Central Asia.” [21]

Xinjiang, like Taiwan and Tibet, has historically been a land of constant unrest and struggles for territory.[22] Michael Clarke claims “Xinjiang is arguably more important to China than Tibet. Xinjiang is China’s largest province, endowed with significant oil and gas resources, and acts as both a strategic buffer and gateway to Central Asia, with the province sharing borders with the post-Soviet Central Asian Republics, Russia, Afghanistan and Pakistan.” [23] Moreover, it is a strategically important region, not only in terms of its natural resources and geostrategic location—historically serving as a security “buffer zone” for “China Proper” against regular invasions by nomadic hordes, and (more recently) the Soviet Union (and perhaps Afghan instability today?)—but also because the preservation of Xinjiang carries immense symbolic importance for Beijing. Stability or instability in Xinjiang will have direct effect on other regions of China. Even though today it would be a highly unlikely occurrence, if Xinjiang succeeded in breaking away from China and gaining independence, it would undoubtedly destabilize other regions that share a long history of restless struggle for independence, most importantly Taiwan and Tibet, and perhaps Inner Mongolia as well.

The Uighur issue was the particular reason behind Chinese efforts to establish the “Shanghai Five” dialogue between China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan in 1996, and its institutionalization into the SCO in June 2001. Through the diplomacy of “separatist containment with neighboring Central Asian states, China tried to assure control over Xinjiang.” [24] Prior to the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the SCO defined its priority to be multilateral cooperation against the “Three Evils” of “separatism, terrorism, and extremism.”

After 9/11, Beijing was successful in turning the international situation to its advantage, the “Uighur issue” policy was given a new connotation, and was now conducted under the umbrella of the larger “War on Terror,” which became an omnipresent concept after the Al Qaeda attacks. Michael Dillon, in his article “Xinjiang and the ‘War against Terror,’” writes:

One reason for China’s enthusiastic espousal of the campaign against terrorism became clear when the Foreign Minister of the PRC, Tang Jiaxuan, claimed in a telephone conversation with his Russian opposite number Igor Ivanov in October 10th [2011] that China was also the victim of terrorism by Uighur separatists…By defining all separatist activity in Xinjiang as terrorist, the government of the PRC is hoping to obtain carte blanche from the international community to take whatever action it sees fit in the region.[25]

China was also successful in concluding agreements with its SCO partners (as well as Pakistan and Nepal) that allowed the extradition of alleged Uighur “terrorists” to China.[26]

Liberal Means

Chinese presence in the economies of the Central Asian states has been experiencing a boom, as China is steadily and inevitably overtaking Russia’s position of the biggest economic partner to the region.

Graph 1: Trade with Central Asia, 1995-2011.

Source: Norwegian Institute of Foreign Affairs, “Central Asia Data-Gathering and Analysis Team,” in the Regional Security Conference, OSCE Academy, 15 September 2012.

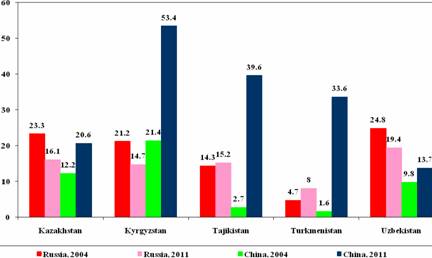

Graph 2: Share of Russia and China in external trade of Central Asian countries (2004 and 2011, % of turnover).[27]

China is investing massively in the construction of infrastructure like railways, roads, aviation facilities, telecommunications networks, and power grids in Central Asia. Its engagement in resource development—in Central Asia most importantly in oil and gas—is increasing. For example, Chinese companies now produce a considerable part of Kazakhstan’s oil output,[28] and the share is, according to some sources, about to grow up to 40 percent by Fall 2013, a share larger than that of Kazakhstan.[29] Likewise, China offered USD 10 billion in loans to the Central Asian states “to support economic cooperation within the SCO,” [30] and promoted establishment of an SCO development bank to aid the member states.[31] However, these actions are not to be perceived as charity. Even though trade with Central Asia accounts for negligible sliver of Chinese total exports, this is a strategically important sliver, as Central Asia accounts for 83 percent of total exports of the restive province of Xinjiang.[32]

To address the threat of separatism and achieve “lasting stability” in Xinjiang, Beijing has undertaken a strategic plan of “leapfrog development,” in addition to a colossal push to “Go West,” otherwise known as the Great Western Development Program. During the visit of President Hu Jintao to Xinjiang in 2009, a month after the tragic ethnic clash, he said that “the fundamental way to resolve the Xinjiang problem is to expedite development in Xinjiang.” [33] Soon Xinjiang was granted “extraordinarily important strategic status” in the nation’s development program. A national work conference on Xinjiang was held to outline the strategic plan of “leapfrog development.” A complex of measures resulted in the establishment of new Special Economic Zone in Kashgar; the granting of the status of special trade zones to the ports of Alatau and Korgas, thus fating the region to become China’s most important gateway to Central Asia; and the implementation of a program of “pairing assistance,” under which nineteen provinces and cities were obliged to provide technical and financial assistance to assigned areas in Xinjiang. On the other hand, the policies of rapid economic development and encouragement of Han migration into Xinjiang were supposed to contain the situation from inside.[34] Chinese leaders definitely took the secessionist threat seriously, and evidently saw the solution to the Xinjiang problem as lying in economic development, driven by the logic that “if the region can develop fast enough, Uyghurs will accept Chinese rule and their dissatisfactions will disappear.” [35]

These domestic developments give significant clues to understanding the drivers of Chinese policies in Central Asia. Foremost part of its long history of statehood, China has been a principally inward-looking power; the policies of “opening up” of the last decades did not necessarily change the nature of Beijing’s interests. According to Wu Xinbo, there is still a strong link between domestic and foreign policies: “China is still a country whose real interests lie mainly within its boundaries.” [36]

That explains the strategy of “double-opening” employed towards Xinjiang in relation to Central Asia – an effort to tie Xinjiang into “China Proper” through simultaneous integration into Central Asian economies while establishing security and cooperation with the Central Asian states. This is how the prominent scholar of Xinjiang Michael Clarke describes this complex strategic logic:

Thus, security within Xinjiang was to be achieved by economic growth, while economic growth was to be assured by the reinforcement of the state’s instruments of political and social control, which in turn was to be achieved by opening the region to Central Asia. Importantly, the economic opening to Central Asia would come to offer Beijing a significant element of leverage to induce Central Asian states to aid it in its quest to secure Xinjiang against “separatist” elements.[37]

Remembering the role of Xinjiang as an important trade hub on the ancient routes of the Great Silk Road, China’s blueprint today is to revive its status as a center for trade, oil and gas being the new commodities traded. Therefore, China’s interest in Central Asian oil and gas is not merely economic; the energy sector serves as a “pillar” industry within Beijing’s Great Western Development strategy.[38] Energy transportation networks that run from Central Asia through Xinjiang directly to the heart of China would gradually create a comprehensive cooperation system that would tie the whole region into a “complex interdependence.” [39] The motivation is threefold. First, it would satisfy China’s growing hunger for energy and diversify its energy supplies, which today are heavily dependent on the Middle East. Second, it will be beneficial to the Central Asian economies, opening them up to the second-largest energy consumer in the world, thus benefiting the economic development of the region. Finally, it will tie Xinjiang simultaneously to Central Asia and China.

Thus economic growth, energy, and strategic interests are inextricably tied together. But the precondition for realizing China’s strategic and energy objectives is founded on the premise of internal stability in Xinjiang. Thus China’s Central Asian policies as a whole are fundamentally strategically conceived and grow out of a preoccupation with the potential for unrest in its lone majority-Muslim province.[40]

The New Frontier

The previous section aimed at providing empirical support for the first hypothesis posed by this paper; its main argument was that China’s policy in Central Asia is an extension of its policies in Xinjiang. This section aims to illustrate the argument postulated by the second hypothesis: “Xinjiang’s place in Chinese foreign policy towards Central Asia is purely pragmatic and economic.” The accompanying sub-hypotheses are: “As one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, China pursues every market it can get, no matter how small or big, and Central Asia is no exception.” And: “Economic development of the previously laggard Xinjiang is in China’s overall development interests.” Accordingly, the postulates of this hypothesis are largely liberal in their nature.

As Michael Clarke argues, Xinjiang’s role all through the Chinese history has been a strategic one.[41] It was a transition zone linking China to the Muslim world and Europe. Throughout the twentieth century, due to certain political circumstances China was unable to utilize the advantageous strategic location of Xinjiang. In addition, Xinjiang was cut off from its “vein of life,” its main historical mission as a crossroad of trade routes connecting the great civilizations of the past. During the entire century landlocked Xinjiang languished on the periphery of the Chinese state, far away from the great economic success of the coastal zones of China.

A 1999 paper stated that “The Chinese government is well aware of the fact that... central and western China, where most minority people live, lags far behind the eastern coastal areas in development.” [42] Indeed, in the beginning of the 2000s an estimated ninety percent of the eighty million Chinese living below the poverty line lived in the western regions of China.[43] Therefore, in order to sustain the overall economic growth of the country, Beijing needed to address the socio-economic issues on its western periphery.

On the other hand, China needed to supply enough energy to satisfy the needs of its people and fuel its continued economic development. In the early 2000s, China realized that it had become a net energy importer, with rapid annual increases of energy consumption. Accordingly, China’s energy objectives in the tenth Five-Year Plan (2000–05) point out that China’s security objectives “must be considered within the national political goal of better integrating China’s eastern and western regions,” and that “Beijing thus will have to resolve, both for reasons of continued economic well-being and domestic tranquility, a national priority of working toward a stable international environment.” [44]

Roughly a decade ago Beijing introduced an ambitious “Go West” campaign designed to bring economic development to the six laggard western regions.[45] Due to its endowment of natural resources, strategic geographical location, and massive arable lands, Xinjiang has been a major target of the campaign. Xinjiang is also a key link to Central Asia, which is no less abundant in natural resources. Central Asian gas and oil, even though they would satisfy only a small part of China’s energy needs, are important in terms of addressing China’s increasing energy deficit and Beijing’s risk diversification strategy. Chinese analyst Lan Peng argues for greater energy cooperation with Central Asia. He maintains that other energy supplying regions all bear high levels of risk. “The Middle East, which has 61 % of global oil reserves and 41 % of natural gas reserves, is politically unstable; Africa has other drawbacks such as societal instability, the risk of terrorism, and its distance from China; Latin America, in geopolitical as well as geographical terms, is too close to the US,” [46] Lan Peng writes, whereas Central Asia is a geographically adjacent, stable region, and its economic development would help to boost the economy and security of Xinjiang.[47] “Central Asia has abundant energy resources, while China has a stable demand for energy. Cooperation between the two sides has excellent prospects,” said Liu Hongpeng, chief of the Energy Security and Water Resources Department of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific of the United Nations during the Second China-Eurasia Expo in Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang, in 2012. At the same venue, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao affirmed Beijing’s far-reaching ambitions:

Cooperation in this field has expanded from simple imports and procurement to both upstream and downstream sectors covering design, prospecting, refining, processing, storage, transport and maintenance. China should build more energy projects, such as the China-Central Asia natural gas pipelines and the China-Kazakhstan oil pipelines, and hasten the creation of new energy pipelines between China and Russia.[48]

Today, China’s infrastructure network “is penetrating an area stretching from Azerbaijan and Iran in the West, to Pakistan in the south, and Mongolia/Central Asia in the north.” [49] A number of Chinese-sponsored roads reach as far as Western Europe. Notably, the massive “Western China–Western Europe” transport corridor, 8,445 km long, and called by some the New Silk Road, is by far the biggest infrastructure project in the region that has enjoyed Chinese support; this road is expected to lead to a four-fold reduction of the delivery time from China to Europe.[50]

With its natural resource export-oriented economy, enormous infrastructure needs, and high demand for low-priced Chinese products, it is difficult to find a region as complementary to China in terms of its economic structure as Central Asia. A home to 66 million people, its market is of interest for China simply on its face. The development of Xinjiang’s role in international trade was announced to be one of the main objectives of the “Go West” program.[51] However, if the efforts of the Chinese government to build up infrastructure have been a facilitator, the role of small traders and truckers is not to be neglected for their importance in supporting the thrust into the region, playing a role that is perhaps even more important than that of the big Chinese corporations. Small businesses are largely responsible for the expansion of China’s market presence in Central Asia, opening up Xinjiang’s markets, and providing employment in the region. In words of Premier Wen Jiabao, “Sound infrastructure can promote people-to-people exchanges and help drive economic cooperation and trade.” [52]

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening up of the borders to the newly independent Central Asian states, Xinjiang once again justified its name of the “New Frontiers” of China. Beijing’s efforts are producing results, as Xinjiang’s economy has been experiencing rapid growth, with annual GDP growth in the region outpacing China’s already impressive national numbers.[53] The “open door policy” adopted toward the neighboring countries has led to massive investments into transportation and energy infrastructure, booming cross-border trade, “as well as a pooling of resources from eastern to western China.” [54] Thus, Chinese policies have had multiple effects. First, they have addressed the issue of energy diversification, as well as China’s growing demand for energy. Second, they have helped to elevate the laggard Xinjiang economy, slowly but surely making it into a Central Asian economic hub. Finally, these policies have opened new markets for Chinese goods in the states of Central Asia.

Rise of a Great Power

This section of the article will put forth the hypothesis that the role of Xinjiang in Chinese foreign policy in Central Asia is driven purely by economic concerns, and is based on pragmatic interests. In turn, this section is an examination of the argument proposed by the third hypothesis, which postulates that Xinjiang is an element of Chinese foreign policy toward Central Asia as a great/major power. The attendant sub-hypotheses here can be stated as: “Xinjiang is the western frontier of China, bordering Central Asia, and its role is only that of border region,” and “A pro-Chinese Central Asia is a way to prevent U.S. encirclement.” A third sub-hypothesis is: “Chinese policy in Central Asia is comparable to Chinese policy in East and Southeast Asia – a strategy of gradual economic-based rise into major-power status and dominance.” And, finally: “If China’s ‘key’ to enter Southeast Asia was the Chinese ethnic and cultural presence there, the Turkic Uighurs of Xinjiang are a key to enter/link up with Central Asia.” Taking the constructivist paradigm as a framework, this section will argue that China’s policies in Central Asia are shaped by China’s perception of itself as a “rising” great power, and Xinjiang’s role in this policy is that of a “key” that will help China gain access to the region.

General Liu Yazhou of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) once said that “Central Asia is the thickest piece of cake given to the modern Chinese by the heavens,” [55] and Xinjiang was to become a “Eurasian Continental Bridge” in words of the veteran CCP leader in Xinjiang Wang Enmao.[56] Xinjiang’s pivotal geopolitical position, as well as its historical and cultural ties with Central Asia, was of great value to China as it tried to expand its influence into Central Asia, simultaneously integrating the separatist province of Xinjiang into greater China. The integration of Xinjiang into Central Asia is not only supposed to reduce the threat of Uighur separatism, but also strengthen China’s geostrategic position on the international stage.

The creation of economic links to the Eurasian inland forms an indispensable part of China’s rise. Without the sustainable development of its interior western regions, social unrest is guaranteed to impede China’s great power ambitions which, for better or worse, is bound to affect all other states’ interests in the region.[57] Xinjiang provides Beijing a justification to assert itself as a Central Asian power. Moreover, it is a “door” for China into the wider Muslim world. Safeguarding the Chinese position in Central Asia and Xinjiang is thus evidently linked to its ability to pursue its global strategy of a “peaceful rise.”

Securing the Rear

“As the squeeze on China’s strategic space intensifies, a stable western region takes on additional importance as a strategic support for the country. The strategic significance of western China is self-evident.” [58] Since the 1990s China has increasingly viewed itself as a major power, gradually coming to embrace its “great power identity.” [59] Chinese sources describe its rise as “daguojueqi” (the rise of a great power). As it tries to shape itself as a great power, however, it is a common belief in China that it is still very weak politically and economically, especially on its western periphery. Some constructivists see the deeply rooted feeling of vulnerability in the collective psyche to be indicative for the Chinese ideology of “the great power rise.” It is argued that, “in contrast to the self-confident American nationalism of manifest destiny, Chinese nationalism is powered by feelings of national humiliation and pride.” [60] The concept of the “century of humiliation” (bainianguo chi), which refers to the hundred years (1840–1949) of “suffering and humiliation” under Western imperialist powers, had a profound impact on Chinese formations of a vision of world politics.[61]

China feels contained, being surrounded by India, Russia, and allies of the U.S. Therefore, opening up Central Asia gave China the potential to develop its western land routes, which are less expensive and more reliable than sea routes (due to U.S. control of sea lanes). The United States’ recently announced “pivot to Asia” and its growing presence in the Asia-Pacific region have only exacerbated Beijing’s fear of being “encircled.” Central Asia is thus becoming “China’s great rear of extreme importance,” a way to break out of the U.S. strategic encirclement.[62]

In geostrategic terms, Central Asia is adjacent to sensitive regions such as the Middle East, Russia, South Asia, and Turkey. It is one of a few regions where the interests of almost all of the major powers meet, and although China does not seek hegemony in the region, it is important for her to prevent anyone else from dominating it. China seeks to build up a kind of a “stability belt” around itself, so it can focus on its domestic development and the more immediate issues of Taiwan and the Southeast Asian region. It is also imperative for China to prevent conflicts and the rise of terrorist activities and Islamic extremism in the region.

Sébastien Peyrouse argues that Central Asia emerged on Beijing’s strategic map “to help China appear as a peaceful rising power able to play the multilateralism card, and to build a specific partnership, one that is economically-based, with the Muslim world.” [63] Central Asia is ideal place to become a “laboratory” for Chinese foreign policy. Here it can test new approaches to conducting foreign policy that are more active and less conservative. Notably, Beijing can demonstrate to the international community its sincerity in the endeavor for a “Peaceful Rise”—a rise without confrontation with other powers, the strategy put forward by Deng Xiaoping’s taoguang yang hui, you suozuowei (keep a low profile and never take the lead).[64]

On the other hand, Konstantin Syroyezhkin says that Central Asia is a “laboratory” for the Chinese rise as not only an economic, but also a normative power. Its political narrative is simple and understandable for the Central Asians, and in contrast to Russia and the U.S., the Chinese treat their smaller partners as equals and “talk business.” [65] Chinese leaders follow the principles of “do good to our neighbors, treat our neighbors as partners” (yulinweishan, yilinweiban) and “maintain friendly relations with our neighbors, make them feel secure, and help to make them rich” (mulin, anlin, fulin).[66] Furthermore, China—at least in its rhetoric—is a strong proponent of the principles of sovereignty and non-interference into the domestic affairs of states, along with its “no norms” policy. This policy has been highly appreciated by the regimes in the region, and has created a positive image of China among Central Asian elites. Besides, it became a valuable asset of Chinese diplomacy by itself—something that Russian (and especially Western powers) often lack in Central Asia. For Central Asian leaders, China represents an attractive alternative to Russian “sticks without carrots” and the Western push for democratization and human rights. China’s “model of market-oriented authoritarianism” might be an attractive direction for the leaders of Central Asia, and “Beijing’s ability to present an alternative political and economic model could be a telling indicator of a growing Chinese ideological influence that is countering the Western perspectives of democratic practice as a prerequisite for economic prosperity.” [67]

In summary, this hypothesis claims that Beijing has utilized Xinjiang’s “intermediate position in Eurasia” in order to enhance its influence in Central Asia.[68] In the process, Beijing hopes that Xinjiang will thus contribute to China’s long-term strategy of “peaceful rise” as a great power, help it escape strategic encirclement by the United States, safeguard important trade routes, and buildup a “stability belt” around China, so it can focus on its more immediate issues. Moreover, this section argued that Central Asia has become a “laboratory” for Chinese diplomacy, and a field on which to test China’s rise as a normative power.

A Mixed Story

The first main hypothesis (a mix of realist and liberal perspectives) assumed that Xinjiang loomed large as a separatist concern for China, and therefore its Central Asian policy is designed to primarily address that internal destabilizing threat. The second main hypothesis (of a more liberal bent) maintained that the economic development of Xinjiang is in China’s overall interests, and Xinjiang’s place in Chinese foreign policy is purely pragmatic and economic. The third main hypothesis (seen from the constructivist perspective) claimed that Xinjiang is an element of China’s great-power strategy, and that Xinjiang’s Uighurs may serve as a link to Central Asia. This section will reflect on the assumptions put forward by the hypotheses, and see whether any of the hypotheses is able to provide helpful guidance about the role of Xinjiang in China’s policies in Central Asia.

Central Asia is on the periphery of the Chinese strategic focus; as a result, China has never clearly articulated a strategy towards the region. However, Central Asia is vital for Xinjiang, a region that is of paramount importance to China in many regards. First of all, this historically restive and separatist region constitutes one-sixth of China’s territory, which is a psychologically significant figure in terms of China’s national identity, and especially in the context of the extreme sensitivity around the notion of “national integrity” for China as a nation. Second, it is a region greatly endowed with a wide variety of natural resources, most notably with oil and gas, most of which are still unexploited. It is home to approximately 25 percent of China’s total national reserves of oil and gas, and 38 percent of its coal reserves.[69] Also enjoying generous annual sunshine and strong steady winds blowing across its deserts and steppes, Xinjiang is the most important part of China’s massive campaign of developing clean energy, part of its push to address the issue of pollution over the next decades.[70] Third, Xinjiang is important due to its geostrategic position, historically being China’s “buffer zone” from instability to the west, as well as serving as its “frontier” into Eurasia. Thus, the desire for stability in Xinjiang is the key to understanding China’s policies in Central Asia.

This section will argue that neither hypothesis—as well as neither of the theoretical approaches—alone reproduces the full picture. While the lenses of defense (realist), development (liberal) and diplomacy (constructivist) are not necessarily contradictory, combined they may complement each other and deepen our understanding about the drivers of Chinese policy toward Central Asia in general, and the role of Xinjiang in particular. The idea behind this reasoning lies in the logic of traditional Chinese policy thinking itself. The idea of comprehensiveness, of everything being interconnected and interdependent, is deeply rooted in Chinese political thinking. China sees comprehensiveness (quanmianhua) as the main element of security.[71] In other words, national strategy is understood in an all-inclusive, inter-connected framework of economic, political, and military dimensions and defense, with development and diplomacy part of an interlinked continuum rather than separate approaches.

Chinese policies in Central Asia and Xinjiang are no exception: “there is a largely complementary relationship between what may be termed China’s Xinjiang, Central Asia and grand strategy-derived interests.” [72] Moreover, it can be said that there is a “largely complementary relationship” between Beijing’s policies being driven by the pursuit of stability in Xinjiang, its economic development, and the overall strategy of China’s rise as a great power. Thus, the hypotheses that were examined above are all parts of one big picture, a picture of a policy that has tilted toward one or another approach over time depending on domestic and international dynamics as interests have also evolved and become more complex.

The current set of Chinese interests in Central Asia did not appear all at the same time, but underwent a process of formation and reconsideration. The first hypothesis, probably, tells us more about the initial priorities and intentions of China in Central Asia. China first started to play a role in the region in the early 1990s, driven by its concern that the acquisition of independence by the Central Asian republics would encourage separatism in Xinjiang. So the policies of China on that stage were directed at assuring the commitment of the newly emerged states to the “One China” discourse, and their support in combating the “East Turkestan” movement. Up until the early 2000s, China did not have any further strategic interests in the region. However, with the opening up of the borders of the Central Asian states to economic activity, the small-scale trade of cheap Chinese goods became an important source of livelihood for people on both sides of the border. The annual trade between Central Asia and China in 1996 and 1997 accounted for less than a billion U.S. dollars.[73]

In the early 2000s, China’s interest started evolving toward the policies better described by the second hypothesis. Beijing undertook a campaign focused on developing its western provinces that was unprecedented in its scale, designed to bring stability to Xinjiang through economic development. The development of Xinjiang’s role in international trade was announced to be one of the main objectives of the program. The idea was that Central Asia is geographically adjacent and culturally close to Xinjiang, so its stability and economic development would help to boost the economy and security of Xinjiang as well.[74] Massive investments into infrastructure projects connecting Central Asia and China have facilitated cross-border trade, as well as attracted larger businesses into developing the region. So, Beijing’s interest in containing separatism did not change, but it reformulated its approach to achieving this goal.

After the 9/11 attacks, China successfully framed its struggle with separatism in Xinjiang as part of the “Global War on Terror,” making Central Asia an important partner in that struggle under the auspices of the SCO’s fight against its “three evils.”China has used the SCO as an instrument to help strengthen its positions in Central Asia without arousing suspicion on the part of the Russians, who traditionally consider Central Asia to be their “backyard” – a zone of immediate interest. On the other hand, China actively exploited bilateral diplomacy in order to build a strong foundation for its advancement into the region. At the same time, in the beginning of the new millennium China found itself as a net energy importer with a seemingly insatiable demand. Diversification of supply became a strategic issue, especially given the impact of the 9/11 attacks on access to global energy markets and the vulnerability of Middle Eastern supplies.[75] These changes in the international arena made energy cooperation an area of primary importance in China’s policy toward Central Asia. Only then did large Chinese corporations start penetrating the region. Xinjiang became a major hub of oil and gas pipelines and a refinery zone for Central Asian energy. Consequently, economic cooperation with Central Asia has brought development in parallel to Xinjiang.

With diminishing Soviet infrastructure and weakening cultural and economic ties between Central Asia and Russia, this new infrastructure encourages Central Asia to begin a gradual turn toward China. Former Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kwan Yew has famously described the economic relationship between China and Singapore as an “elephant on one side and a mouse on the other,” arguing that China is no longer interested in promoting its regional ambitions through military means, but rather that “the emphasis is on expanding their influence through the economy.” [76] The same conclusion can be easily drawn by examining Chinese policies in Central Asia as it rises as a great power. The integration of Xinjiang into Central Asia is not only supposed to reduce the threat of Uighur separatism, but also to strengthen China’s geostrategic position on the international stage. The United States’ recently announced “Pivot to Asia” and its reinsertion of its presence in the Asia-Pacific makes the preservation of Chinese influence with its western neighbors ever more strategic, making it a way to escape U.S. “encirclement.” Thus, the propositions made by the third hypothesis are becoming more viable in Chinese strategy with time.

Consequently, China’s priorities and interests have changed over time, becoming more complex and interconnected, involving more “layers” of interests to interact and reinforce each other. What may look like a cohesive strategy of a Chinese rise in Central Asia appears to reflect the reality of a dynamic equilibrium that has been reached between Chinese material and ideational interests and incentives on the one hand, and the set of strategic reactions and interactions on the part of Central Asian states with China on the other. What we witness today is the result of adaptation strategies and reactive policies to dynamics of both an internal and external nature.

The role of Xinjiang remains essential at every level of Chinese interest in Central Asia, making it a kind of a “conductor” for Chinese policies. Accordingly, it has multiple functions. First of all, separatism in Xinjiang is a threat to Chinese territorial integrity; however, Xinjiang is also a “buffer zone” that protects “China Proper” from any possible instability in Central Asia. Xinjiang serves as a bridge for Chinese economic expansion into Central Asia, and a gateway through which China can channel its political influence. Chinese policy in Central Asia is a tale of how a security challenge (the breakup of the Soviet Union), translated into the need for stability beyond Xinjiang (the buffer zone model) that was ensured through economic benefit, and of subsequent economic expansion (the “bridge” function), which brought about political influence and a strategic windfall.

What China gets in the end is its five main priorities being fulfilled:

- Stability in Xinjiang and preservation of the territorial integrity of China

- Economic dividends and westward development

- Diversification of energy sources

- Central Asia as a sphere of influence

- A way to break out of the strategic “encirclement” of the “rising great power.”

Taken as a whole, China’s strategy presents a complex web of linkages between its imperatives of integration and control within Xinjiang, its drive for security and influence in Central Asia, and its overarching quest to achieve a “peaceful rise” to great power status.[77]

Conclusion

This essay has offered an exploration of the place of Xinjiang in Chinese policies towards Central Asia. What is the role of Xinjiang in China’s policy in Central Asia? Is Chinese engagement with Central Asia mediated in any way by its domestic policies and concerns over Xinjiang? These were the questions that the research aimed to explore. Hence, China in this paper was examined as an object, Central Asia as a subject, and Xinjiang as a factor.

The essay was impelled by the fact that most studies of Chinese policies in Central Asia widely agree that concern over separatist tendencies in Xinjiang has been the main driver of Beijing’s policies in Central Asia. With the growing interest in the “Chinese Rise” in the world, as well as in academia, this paper aimed at analyzing the often neglected Central Asian aspect of this rise. Viewing Central Asia through the lens of Xinjiang, it aimed to systematize the many different facets of Xinjiang’s role in this “rise.”

Drawing from the main arguments made in the literature, this paper posed three sets of hypotheses. To summarize, the first main hypothesis claimed that Xinjiang is a significant separatist concern for China, and therefore its Central Asian policy is designed to address and manage that threat. The second main hypothesis maintained that Xinjiang’s economic development is in China’s overall interests, and Xinjiang’s place in Chinese foreign policy is purely pragmatic and economic. The third main hypothesis asserted that Xinjiang is an element of China’s great-power strategy, and that its role is to serve as abridge to Central Asia.

The study concluded that there is a complementary relationship between Beijing’s policies in Central Asia being driven by aspirations to stabilize Xinjiang, economic interests, and the wider strategy of China’s rise as a great power. It is argued that neither hypothesis alone can reflect the full picture. However, the arguments made in the hypotheses do not necessarily contradict each other, but rather are all parts of an interrelated continuum between state-directed means and ends, as well as strategic actions and reactions. Depending on domestic and international dynamics, China’s interests and priorities in Central Asia have also evolved, becoming more complex and interconnected. Like different sedimentary strata, the new imperatives, interests, and tactics form on top of a previous ones, complicating the policy, making it more diverse and profound. The role of Xinjiang remains essential at every layer of Chinese interest in Central Asia. The strategy of opening up of Xinjiang to Central Asia in order to pacify it has borne fruit, and has resulted in the expansion of China’s political influence in the region. What may look like a cohesive, considered strategy of the “Chinese rise” appears to be more of a result of adaptation strategies and reactive policies to changing internal and external dynamics.

Outlining avenues for future research, this article suggests that it would be fruitful to examine the role that Xinjiang has played in the formation of Central Asian foreign and security policy. What does the rising Chinese influence mean for Central Asia? Is it a threat or an opportunity? Furthermore, is China acting in a way that imposes domestic constraints on the Central Asian states? In other words, how does the rise of China impact the multi-vector policies of the Central Asian governments? Does it happen intentionally—by design—or by default? Or, flipping the perspective, does it happen intentionally or involuntarily, i.e., by invitation or by imposition? This is a potentially productive direction of further study and research.

* Tukmadiyeva Malika is a recent graduate of the joint Master’s Program of the Geneva University and the Geneva Center for Security Policy, Geneva, Switzerland. Her principal academic interest lies in the field of Central Asian politics (including Afghanistan and Xinjiang): energy politics, elites, nationalism, regionalism, and Chinese influence in Central Asia.

[1] “China’s Investment in the Countries of Central Asia Are Almost $250 Billion—Wen Jiabao,” Kyrgyz Telegraph Agency (2 September 2012); available at www.kyrtag.kg/?q=ru/news/26981.

[2] Joshua Kucera, “Central Asia: What is China’s Policy Driver?” Eurasianet.org (18 December 2012); available at http://www.eurasianet.org/node/66314.

[3] Sébastien Peyrouse, Jos Boonstra, and Marlène Laruelle, “China in Central Asia,” EUCAM (5 March 2013); available at http://isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Articles/Special-Feature/Detail/?lng=en&id=160545&contextid774=160545&contextid775=160542&tabid=1454181096.

[4] Sometimes also spelled “Sinkiang.”

[5] Sébastien Peyrouse, “Central Asia’s Growing Partnership with China,” EUCAM Working Paper No. 4 (2009), 6.

[6] As an extensive pipeline network between Central Asia and China is currently being expanded, Chinese dependence on Central Asia in terms of energy supplies is likely to grow. Currently, China’s oil imports mainly come from the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, while Central Asia accounts for approximately 4 percent of Chinese oil, and 10 percent of gas imports, mainly from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. See Niklas Swanström, “China and Greater Central Asia: New Frontiers?” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program (2011): 53.

[7] Huasheng Zhao, “Central Asia in China’s Diplomacy,” in Central Asia: The View from Washington, Moscow, and Beijing, ed. Eugene B. Rumer, Dmitriy Trenin, and Huasheng Zhao (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2007), 154.

[8] “Interview with Konstantin Syroyezhkin,” ObshestvenniiReiting (1 December 2011); available at http://www.pr.kg/gazeta/number553/1927/.

[9] Stephen Blank, “Xinjiang and China’s Strategy in Central Asia,” Asia Times Online (3 April 2004); available at http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/FD03Ad06.html.

[10] Due to the limitations of this essay, it will not dwell upon the historical and cultural links between Central Asia and Xinjiang. However, the links are apparent to the extent that Xinjiang has been continuously included by many experts within the larger construct referred to as “Central Asia.” For further information on this topic, see Michael E. Clarke, Xinjiang and China’s Rise in Central Asia, 1949-2009 (London: Routledge, 2011).

[11] Cobus Block, “Bilateral Trade Between Xinjiang and Kazakhstan: Challenges or Opportunities?” China Policy Institute Blog (7 February 2013); available at http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/chinapolicyinstitute/2013/02/07/bilateral-trade-between-xinjiang-and-kazakhstan-challenges-or-opportunities/.

[12] Niklas Swanström, “China’s Role in Central Asia: Soft And Hard Power,” Global Dialogue 9:1–2 (2007); available at http://www.worlddialogue.org/content.php?id=402.

[13] Huasheng Zhao, “Central Asia in China’s Diplomacy,” 139.

[14] Justin V. Hastings, “Charting the Course of Uyghur Unrest,” The China Quarterly 208 (2011): 911.

[15] Shan Wei and Weng Cuifen, “China’s New Policy in Xinjiang and its Challenges,” East Asian Policy 2:3 (2010): 61; available at www.eai.nus.edu.sg/Vol2No3_ShanWei&WengCuifen.pdf.

[16] “Russian-Led Customs Union Intensifies Sino-Russian Rivalry in Central Asia,” Global Security News (4 August 2011); available at http://global-security-news.com/2011/08/ 04/russian-led-customs-union-intensifies-sino-russian-rivalry-in-central-asia.

[17] I would like to thank Dr. Emil Dzhuraev and Dr. Graeme Herd for their enormous support and invaluable assistance in defining and formulating the main focus and hypotheses of this paper.

[18] Swanström, “China’s Role in Central Asia,” 12.

[19] Michael Clarke and Gaye Christofferson, “Xinjiang and the Great Islamic Circle: The Impact of Transnational Forces on Chinese Regional Economic Planning,” The China Quarterly 133 (1993): 130–51.

[20] Michael Clarke, “China’s Xinjiang Problem,” The Interpreter (10 July 2010); available at http://www.lowyinterpreter.org/post/2009/07/10/Chinas-Xinjiang-Problem-Part-1.aspx.

[21] Ann McMillan, “Xinjiang and Central Asia: Interdependency, not Integration,” in China, Xinjiang and Central Asia: History, Transition and Crossborder Interaction into the 21st Century, ed. Colin Mackerras and Michael Clarke (London: Routledge, 2009), 96.

[22] Stephen Blank, “Xinjiang and China’s Strategy in Central Asia.”

[23] Clarke, “China’s Xinjiang Problem.”

[24] Donald H. McMillen, “China, Xinjiang, and Central Asia: ‘Glocality’ in the Year 2008,” in China, Xinjiang and Central Asia: History, Transition and Crossborder Interaction into the 21st Century, ed. Colin Mackerras and Michael Clarke (London: Routledge, 2009), 9.

[25] Michael Dillon, “Xinjiang and the ‘War against Terror’: We Have Terrorists Too,” The World Today 58:1 (2002), quoted in McMillen, “China, Xinjiang, and Central Asia,” 14.

[26] Michael Clarke, “Xinjiang Problem: Dilemmas of State Building, Human Rights and Terrorism in China’s West,” Human Rights Defender 21:1 (2012): 16-19.

[27] From Andrei Zagorski, “Share of Russia and China in external trade of Central Asian countries (2004 and 2011, % of turnover),” GCSP, presentation on 4 March 2013: 7.

[28] “Kazakhstan May Hand Kashagan Stake to China,” BusinessNewEurope (17 April 2013); available at http://www.bne.eu/story4823/Kazakhstan_may_hand_Kashagan_stake_to_China.

[29] “Chinese Companies to Control Over 40 % of Kazakhstan’s Oil Shortly,” Tengrinews.kz (8 January 2013); available at http://en.tengrinews.kz/markets/Chinese-companies-to-control-over-40-of-Kazakhstans-oil-shortly-15796/.

[30] “China Offers 10-Bln-USD SCO Loan,” Xinhua News Service (6 July 2012); available at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-06/07/c_131637089.htm.

[31] “Xi’s Central Asia Trip Aimed at Common Development, All-Win Cooperation,” Xinhua News Service (15 September 2013); available at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-09/15/c_125389057.htm.

[32] Block, “Bilateral Trade Between Xinjiang and Kazakhstan.”

[33] Shan Wei and Weng Cuifen, “China’s New Policy in Xinjiang and its Challenges,” 61.

[34] Ibid., 61.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Wu Xinbo, “Four Contradictions Constraining China’s Foreign Policy Behaviour,” in Chinese Foreign Policy: Pragmatism and Strategic Behaviour, ed. Suisheng Zhao (New York: East Gate Books, 2004), 58.

[37] Clarke and Christofferson, “Xinjiang and the Great Islamic Circle,” 165.

[38] Clarke and Christofferson, “Xinjiang and the Great Islamic Circle,” 130–51.

[39] Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, “Power and Interdependence Revisited,” International Organization 41:4 (1987): 725–53.

[40] Stephen Blank, “Xinjiang and China’s Strategy in Central Asia.”

[41] Michael Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia: Securing a ‘Silk Road’ to Great Power Status?” China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly 6:2 (2008): 90.

[42] Dru C. Gladney, “The Chinese Program of Development and Control, 1978–2001; Responses to Chinese Rule: Patterns of Cooperation and Opposition,” in Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, ed. S. Frederick Starr (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2004), 337, cited in Marissa A. Dorais, “The Go West Campaign in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China: Water Scarcity and Economic Growth” (Environmental Studies Senior Project, Lewis & Clark College, 2005); available at http://enviro.lclark.edu/students/projects/2005-06/2005-06forweb/mdorais.pdf.

[43] Elizabeth Economy, “China’s ‘Go West’ Campaign: Ecological Construction or Ecological Exploitation?” China Environment Series 5 (2002): 4.

[44] Bernard Cole, “‘Oil for the Lamps of China’ – Beijing’s 21st-Century Search for Energy,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, McNair Paper 67 (October 2003), 50; available at http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA421818.

[45] Economy, “China’s ‘Go West’ Campaign,” 4.

[46] Lan Peng, “An Analysis of the Feasibility of Cooperation in the Energy Sector Between China and Central Asia Based on the SWOT Method (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats),” KejiaoDaokan – The Guide of Science and Education (November 2011): 240–41; cited in “The New Great Game in Central Asia,” European Council on Foreign Relations (2011); available at http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China%20Analysis_The%20new%20Great%20Game%20in%20Central%20Asia_September2011.pdf.

[47] Ibid.

[48] “China Seeks Regional Energy Cooperation as Challenges Mount,” People’s Daily Online (6 September 2012); available at http://english.people.com.cn/90778/7938283.html.

[49] Swanström, “China’s Role in Central Asia.”

[50] “West Europe–West China Project to Increase Deliveries by Trucks Almost Four-fold,” Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, May 2007; available at http://en.government.kz/site/news/052007/04.

[51] Economy, “China’s ‘Go West’ Campaign,” 4.

[52] “China Seeks Regional Energy Cooperation as Challenges Mount.”

[53] China Bureau of Statistics (2010) cited in Gloria Chou, “Autonomy in Xinjiang: Institutional Dilemmas and the Rise of Uighur Ethno-Nationalism,” The Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies 4 (2012): 170.

[54] Swanström, “China’s Role in Central Asia,” 41.

[55] Joshua Kucera, “China: What’s Next?” The Diplomat (2011); available at http://thediplomat.com/whats-next-china/central-asia.

[56] Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia,” 96.

[57] Swanström, “China’s Role in Central Asia,” 14.

[58] Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia,” 110.

[59] Qianqian Liu, “China’s Rise and Regional Strategy: Power, Interdependence and Identity,” Journal of Cambridge Studies 5:4 (2010): 76-92; available at http://journal.acs-cam.org.uk/data/archive/2010/201004-article7.pdf, 86.

[60] Suiseheng Zhao, “Chinese Nationalism and Its International Orientations,” Political Science Quarterly 115:1 (Spring 2000): 1-33, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2658031.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia,” 109.

[63] Sébastien Peyrouse, Jos Boonstra, and Marlène Laruelle, “Security and Development Approaches to Central Asia. The EU Compared to China and Russia,” EUCAM Working Paper 11 (2012), 11.

[64] Maria Dolores Cabras, “China’s Peaceful Rise and the Good Neighbor Policy,” The European Strategist (11 December 2011); available at http://www.europeanstrategist.eu/2011/12/china%E2%80%99s-peaceful-rise-and-the-good-neighbor-policy.

[65] Konstantin Syroyezhkin, China-Kazakhstan: From Cross-Border Trade to Strategic Partnership, Book 2 (Almaty: The Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies, 2010), 84–85.

[66] Bates Gill and Yanzhong Huang, “Sources and Limits of Chinese ‘Soft Power,’” Survival 48:2 (2006): 20, cited in Chin-Hao Huang, “China and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Post-Summit Analysis and Implications for the United States,” The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly (2006): 17.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia,” 91.

[69] “Xinjiang’s Natural Resources,” China Trough a Lens; available at www.china.org.cn/english/material/139230.htm.

[70] Jeffrey Hays, “Wind Power and Solar Energy in China,” Facts and Details, 2008, available at http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat13/sub85/item318.html

[71] Russell Ong, “China’s Security Interests in Central Asia,” Central Asian Survey 4:24 (2005): 425.

[72] Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia,” 89.

[73] Huasheng Zhao, “Central Asia in China’s Diplomacy,” 138.

[74] Lan Peng, “An Analysis of the Feasibility of Cooperation in the Energy Sector,” 240–41.

[75] Huasheng Zhao, “Central Asia in China’s Diplomacy,” 138.

[76] Shaun Breslin, “China’s Rise to Leadership in Asia – Strategies, Obstacles and Achievements,” paper presented at the Conference “Regional Powers in Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Near and Middle East,” held at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Hamburg, 11–12 December 2006.

[77] Clarke, “China’s Integration of Xinjiang with Central Asia,” 111.

- 79001 reads

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML