Balancing Defense and Civil Support Tasks: The Impact of Covid-19 on the Bulgarian Military’s Roles

Тип публикация:

Journal ArticleИзточник:

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Volume 19, Issue 2, p.61-76 (2020)ключови думи:

Counter-terrorism, COVID-19, crisis management, defense support to civilian authorities, emergency management, law enforcementАнотация:

Military organizations are often called upon to contribute with specific capabilities or to enhance the civilian response capacity in an emergency at home, in particular, when urgent action in a high-risk environment is needed. The emergency related to the Covid-19 pandemic was not an exception. The Bulgarian armed forces have already made an important and highly visible contribution and are prepared to perform additional tasks assigned through the new emergency law. Both the society and the political elites appreciate this military involvement, and ideas for new civil security tasks have emerged. Based on the analysis of legal and doctrinal documents and the responses to an interview, this article provides an overview of the domestic tasks of the Bulgarian armed forces prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, new tasks assigned during the pandemic and the possibilities for and the caveats in the further expansion of the spectrum of domestic tasks. The opinions of 41 respondents in the interviews are almost equally split. A slight majority suggests further expansion of the domestic tasks, serving as a back-up, and building on high-tech capabilities the armed forces already possess or plan to develop. The remaining respondents call for exercising caution, assuring that the military contribution is effective and efficient, and reconsidering the newly assigned coercive tasks. The article also presents the decision-making context, shaped by long-delayed modernization, limited budget, and the severe shortage of personnel. This is the context in which policy-makers need to find an adequate balance between defense and civil support roles and capabilities.

Introduction

The Bulgarian armed forces, just like the armed forces in many other countries, have three main roles: defense of the sovereignty and the national territory, contribution to international peace and security, and contribution to internal security, particularly in times of crises. In peacetime, the third of these roles is most visible to society. The military contribution during the Covid-19 pandemic makes no exception. The urgency of the situation, the uncertainty surrounding the new viral threat and its impact, and the limited civilian capacity to act in a contaminated environment sharply increased the interest in the contribution of the armed forces.

In a matter of days, new tasks for the armed forces were codified in law. The military contribution in the pandemic-related emergency so far is largely seen as positive, and although some of the new tasks have yet to be performed, observers suggest a wider involvement of the armed forces. The appetite for assigning new tasks to the military in their third role may grow in the forthcoming election period without giving proper consideration to the wider effects on defense.

The study presented in this article was undertaken with the aim of clarifying the current situation, the options and the rationale for the military contribution to emergency and crisis management on home territory, and the feasibility of assigning new tasks to the armed forces. The results are based on a review of relevant laws, doctrinal documents and annual reports, and on an analysis of responses to interviews. The author designed a structured questionnaire [1] on the impact of Covid-19 on the defense policy of Bulgaria at the beginning of May 2020 and it was sent out to 65 experienced defense practitioners and analysts (avoiding experts in the executive branch that are currently involved in policymaking or implementation). Forty-one responses were received on time to be considered for this study. Respondents included current members of the Defense Committee in the National Assembly, former Defense Ministers, former Chiefs of Defense and other flag officers, academics from defense academies and research institutes, and experienced practitioners. Respondents have only been named when they have explicitly agreed to be quoted. The study has included content analysis [2] only of the responses to the first question that is related to the internal role and tasks of the armed forces.

The following three sections of the article present, respectively, the domestic tasks of the Bulgarian armed forces prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, new tasks assigned during the pandemic, and the possibilities for and the caveats in the further expansion of the spectrum of domestic tasks. The final section delineates two main options for the future and puts the respective decision making into context.

Domestic Tasks of the Bulgarian Armed Forces prior to the Covid-19 Pandemic

The 1999 Military Doctrine of the Republic of Bulgaria—the first doctrinal document open to the public—defined as one of the main goals of defense “the protection of the population in natural disasters, industrial catastrophes, and dangerous contamination in the country and abroad.” [3] The first White Paper on Defense and the Armed Forces, published in 2002, clearly defined the military support to civilian authorities and the population as one of the three main roles of the national military, along with “Defense” and “Contribution to international peace and security.” According to the 2010 White Paper, this “third role” [4] includes

… operations to deter and neutralize terrorist, extremist and criminal groups; protection of strategic sites; protection and support to the population during natural disasters, accidents, and ecological catastrophes; explosive ordnance disposal; humanitarian assistance; assistance to the control of migration; search and rescue activities; assistance, when necessary, to other state and local authorities for preventing and overcoming the consequences of terrorist acts, natural disasters, ecological and industrial catastrophes, and dangerous spread of infectious diseases.[5]

Consequent doctrinal documents elaborated further on the organizational roles and procedures for the implementation of this role of the armed forces.[6]

Until 2015,[7] explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) and the contribution to disaster management and protection of the population were the main drivers for maintaining capabilities and readiness in this role. Both tasks call for the regular involvement of the armed forces. By 2019, the Bulgarian armed forces maintain 99 formations for containment and recovery from disasters and two groups to support the evacuation of the population in case of an accident in the “Kozloduy” Nuclear Power Plant, with total personnel of 1932 and 550 pieces of specialized equipment, including helicopters for aerial firefighting.[8] In addition, dozens of mobile EOD teams disposed of 503 explosive devices in 2018,[9] and another 188 devices in 2019.[10] Another highly visible task is the medical evacuation by air, performed by the Air Force, maintaining on duty one military transport airplane and one helicopter, and teams from the Military Medical Academy.[11]

Nevertheless, details of the expected contribution of the armed forces in their third role remained largely undefined until the migration crisis of 2015-2016, which became another major driver for reconsidering and codifying in law the domestic tasks of the armed forces. Two amendments to the Law on Defense and the Armed Forces clarified existing tasks and introduced some new ones.[12] These amendments introduced new legal requirements for support to the Ministry of the Interior and other civilian organizations, that included:

- maintaining readiness for and providing humanitarian assistance and rescue on the territory and in the maritime zone of the country and abroad;

- assisting the security agencies in countering the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, the illegal trafficking of armaments, and terrorism;

- protection of strategic sites, assets, and systems of critical infrastructure;

- conducting special operations for countering terrorism and overcoming the consequences of terrorist acts;

- participation in the protection of the state borders;

- conducting special purpose flights for the needs of other ministries and agencies.[13]

All these tasks require additional training and maintaining readiness. The most demanding of them has been the military contribution to the protection of the land borders, primarily the border with the Republic of Turkey. Military engineers built a fence in sectors of that border that were considered to be more vulnerable to illegal migration. The Land Forces were tasked with contributing to the surveillance and control of the border and maintaining their readiness for a battalion-sized reinforcement of the “Border Police” service of the Ministry of the Interior. In 2017, the average monthly contribution amounted to 240 personnel and 70 pieces of equipment.[14] In the first five months of 2018, the military contributed with approximately 700 soldiers in border surveillance and control tasks, and 435 soldiers and 234 pieces of equipment in related logistics functions.[15] This support operation was terminated in May 2018; yet, the military continues to maintain 350 personnel on 24-hour readiness to support the “Border Police” in case the migration pressure increases again.[16]

The Law on Counter-terrorism, adopted in 2016, gave the armed forces typical law enforcement functions in suspected terrorist activities, including the use of force.[17] For that purpose, three services, the Military Police, the Special Operations Brigade, and the Military Medical Academy, could be required to provide up to 1100 personnel with the necessary armaments and equipment.[18] The Land Forces alone have trained and maintain at permanent readiness 30 mechanized and alpine platoons and one CBRN module to support counter-terrorist activities of the Ministry of the Interior.[19]

All these examples demonstrate that, when a need arises, the state leadership is willing to assign support tasks to the armed forces, and to amend the legal framework accordingly. The Ministry of Defense has the experience and the institutional mechanisms in place to provide the requested capabilities, to maintain an adequate level of readiness, and to contribute when necessary. That was also the case with the Covid-19 pandemic.

New Tasks Related to the Covid-19 Pandemic

In unexpected ways, the pandemic made the domestic roles of the military even more visible. The country already had a standing plan for action in a pandemic of influenza [20] which, in line with the Law on Disaster Protection,[21] assigns the lead governance role to a National Pandemic Committee with a Vice Prime Minister as Chair, the Minister of Health as Deputy Chair, and deputy ministers of involved ministries, including the defense ministry, as members.

On March 13, 2020, the Bulgarian Government declared an emergency situation and imposed numerous restrictive measures. In a surprising move, the Government decided to create a “National Operational HQ” (NOHQ) and appointed Major-General Ventsislav Mutafchiiski, professor, military surgeon, and Director of the Military Medical Academy (MMA), as its Chair. The head of one of the MMA departments became NOHQ Secretary. The NOHQ also included two other medical experts—the Director of the National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases and the State Health Inspector—as well as three senior officials from the Ministry of the Interior.

For nearly two months, NOHQ was giving briefings twice a day. It presented not only health-related data, such as the number of tests performed, new cases of infection, hospital patients, cases in intensive care, numbers of death and recoveries, but also additional measures for containment of the pandemic and ways for their implementation. The majority of the citizens, restrained in their homes, waited eagerly for these briefings. General Mutafchiiski, almost always in uniform, spoke with calm and authority on both health and organizational issues. Soon, he became a household name, receiving international recognition,[22] and gaining the approval of over 71 percent of Bulgarian citizens, surpassing the ratings of any active politician considerably.[23]

NOHQ has been so influential in managing the Covid-19 emergency, that only more careful observers have noticed it is supposedly only there in an advisory role. In fact, the law on the Covid-19 emergency assigned most of the decision-making authority to the Minister of Health, while referring to NOHQ only twice in its transitional provisions.[24]

Notwithstanding the legal powers of NOHQ, the Military Medical Academy has demonstrated convincingly its capacity as the leading national institution in a pandemic scenario and its capabilities for:

- testing for the presence of a little-known virus;

- treating infected people (including most of the cases in the first days of the pandemic);

- advising and training other test laboratories and hospitals on how to use safely protective masks and clothing in the presence of biohazards;

- implementing a combination of health and organizational measures for containment during a pandemic.

The armed forces provided other types of support as well. At the time, when the available hospital capacity to accept infected people was of major concern, the military demonstrated its ability to deploy field hospitals in the capital city of Sofia and several other big cities in the country. Furthermore, at times when protective equipment was scarce and there were significant limitations on civilian air traffic, Bulgaria used the NATO-based multinational Strategic Airlift Capability, and Zhasmina Hristova, a female Air Force captain, landed at Sofia airport a C-17 “Globemaster” containing much needed medical supplies. In another example, and even before the declaration of an emergency, the Bulgarian Defense Institute provided results of testing protective masks and clothing, thus certifying the capacity of Bulgarian companies to meet the increasing demand for high-quality products for the protection of medical personnel in Bulgaria and abroad.

Particularly important for this discourse is the authorization of armed forces’ personnel to perform typical police functions. The “Law on the Measures and Activities during the Emergency” authorizes military personnel, “jointly and/or in coordination with other bodies … to participate in the implementation of counter-epidemic measures and constraints on the territory of the country, over a specific area or at a checkpoint.” [25] The law leaves to the Council of Ministers the definition of conditions and procedures for such use of the armed forces.

The same law authorizes military personnel to:

- check the identity of a person;

- restrain the movement of a person who refuses to or does not adhere to quarantine measures, until the arrival of representatives of the Ministry of the Interior;

- stop vehicles until the arrival of representatives of the Ministry of the Interior;

- confine the movement of persons and vehicles at a checkpoint;

- use physical force and respective means when this is absolutely necessary.[26]

The assignment of such typical police functions to the military raised questions among observers. In a TV interview after the emergency law was adopted, Defense Minister Krassimir Karakachanov stated that “the participation of the military during the emergency will start first by replacing the Ministry of the Interior in protecting the border, strategic sites, embassies, and only then one can consider patrolling the streets. … First, that needs to be requested by the Minister of the Interior, and then the Council of Ministers will decide [whether and how to use the military].” [27]

At the time of writing this article, the military has not been called upon to perform such police functions, and the Council of Ministers has not issued a document specifying further the stipulations of the emergency law.

Future Tasks for the Bulgarian Armed Forces in their Domestic Role

This section of the article builds on the expert responses to the first question in the questionnaire:

What needs to be changed in the tasks assigned to the Bulgarian military (different from warfighting), for example, border control, area isolation, establishing and operating checkpoints, transport, logistics (e.g., field hospitals), provision of communications and information support, cybersecurity, countering propaganda and disinformation, etc.?

The question deliberately included among the examples three groups of tasks: (1) some that are already performed by the military, e.g., aerial transport or contribution to border control under increased migration pressure; (2) tasks that are legally prescribed, but not yet implemented, e.g., area isolation, establishing and operating checkpoints during an emergency; and (3) tasks that have been subject of discussion but, strictly speaking, have not been assigned to the armed forces. Among the latter are cybersecurity and countering hybrid influence – areas in which the military is responsible for protecting its own systems and personnel.[28] Hence, any response of the type “the military needs to perform all of the listed tasks” is treated as an opinion to expand the internal role of the military by assigning new tasks.

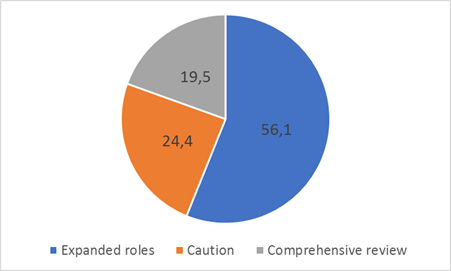

None of the 41 respondents rejected the need for, nor the utility of, the military contribution in times of emergency. Further, and based on content analysis, the responses were split into three main groups (see Figure 1):

- 23 of the respondents—a majority of 56 %—support the implementation of all listed tasks, and some of them suggest that the military might undertake even further tasks in assisting civilian authorities with specific capabilities or by adding capacity in periods of increased demand, i.e., in an emergency or a crisis;

- Ten respondents (24.4 %) were cautious about adding new tasks feeling that they may have adverse, rather than positive, effects on societal security and the status of defense and the armed forces;

- Eight respondents, possibly in line with the thinking of the second group, called for a rigorous and comprehensive review of all the domestic tasks of the armed forces, leading to their prioritization and a balance among the three military roles.

The further elaboration in this section adds detail to the expert opinions and is organized in five topics: the possibility to add capacity to crisis response, the military contribution with specific capabilities, recommended organizational changes, the rationale for caution, and ways to find a proper balance.

|

Figure 1: Distribution of the Response in Percentage Points.

Adding Capacity

Most interviewees agreed that the military should continue to play an active and visible role in emergencies, preferably as a back-up to civilian authorities and with a contribution aimed at achieving decisive effects.

As expected, the emphasis was on the use of the medical capability, including the deployment of field hospitals. One respondent pointed out that field hospitals could be established next to international airports, thus allowing arriving passengers who are sick or infected to be quarantined effectively. Among the related tasks are CBRN reconnaissance and decontamination, as well as the disinfection of public spaces and facilities using specialized military equipment.

In the opinion of Col. Orlin Nikolov, Director of the NATO Center of Excellence in Crisis Management and Disaster Response in Sofia, in a massive crisis the military could also assist the civilian authorities and the population by:

- deploying units for field testing (to identify viral or other infections);

- creating mobile medical teams to serve the population in military garrisons;

- performing social support tasks, e.g., delivery of food and medicines to old or disabled citizens, as well as to people under quarantine (involving cadets from the military academies);

- providing psychological support to the population;

- providing satellite observation of sectors of particular interest.

Several experts emphasized that the armed forces need to build on the strengths of existing military capabilities, e.g., established command and control infrastructure, mobility, and the ability to act in infected environments. These capabilities may be used to enhance the capacity of the Ministry of the Interior and other civilian entities to protect critical infrastructures and control the land borders effectively. Other respondents underlined the potential benefits of deploying military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) teams and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to enhance the surveillance of borders and other areas of interest.

Several respondents pointed to the opportunities provided by the defense research and educational community in designing, testing, and certifying new protective materials, organizing multi-agency training, and similar tasks.

Two respondents indicated the, so far, unexploited capacity of the armed forces’ reserve units and personnel.

Adding Capabilities

Experts see benefits in the contribution of specific military capabilities. Directly related to the pandemic are Role 1 medical evacuation modules and Role 2 mobile, forward-positioned medical treatment facilities and surgical teams, and advanced biological protection capabilities. In particular, the knowledge and capacity to deal with more “exotic” infectious diseases would obviously be of use.

Of particular interest are the capabilities of the “Military Police” service to establish and operate checkpoints and perform other law enforcement tasks.

Several experts referred to the communications and cyber defense capabilities of the armed forces. For example, Dr. George Sharkov, cyber defense coordinator, sees a possibility for undertaking tasks in providing encrypted telecommunications, including in mobile video teleconferencing, and the cyber protection of critical infrastructures, with a focus on the energy, transport, and health sectors.

One expert pointed to the potential utility of capabilities to provide civil-military coordination (CIMIC), human intelligence (HUMINT), and psychological operations. Although developed for other purposes, they may contribute to emergency operations at home, e.g., to counter the spread of fake news, propaganda, and disinformation.

Four respondents emphasized the need to analyze the experience accumulated in NATO and EU disaster response arrangements and to seek the most suitable tasks for the Bulgarian armed forces in the broader framework of allied and regional cooperation in emergency management.

Dedicated Organizational Arrangements

Several respondents used the opportunity to suggest organizational changes that, in their opinion, would make the military contribution to civil security more effective.

Flotilla Admiral Boyan Mednikarov, Commandant of the Bulgarian Naval Academy, suggested that the capacity of the Military Medical Academy could be increased and that it could be used as the national medical institution specializing in crises.

Col. (ret.) Vilis Tsurov, Chairman of the Association of the Officers in the Reserve “Atlantic,” called for the establishment of new branches of the armed forces, including CIMIC and strategic communication (STRATCOM) units to counter propaganda and disinformation, as well as units that could operate aerial, surface and sub-surface drones and conduct anti-drone operations.

Admiral Mednikarov elaborated on the need for establishing a Cyber Command in the armed forces and cyber operations units at service, brigade, and battalion levels. Col. Orlin Nikolov echoed these ideas suggesting the establishment of brigade-level cybersecurity and STRATCOM units, the latter dedicated primarily to countering propaganda and disinformation.

One expert responded that the importance of the cyber and the psychological dimension of conflicts and emergencies would increase and that the military medical and cyber components would need to be strengthened. This expert sees, as the most relevant organizational solution, the creation of specialized battalion level units subordinated directly to the defense minister.

Col. Tsurov considered the most relevant organizational solution to be the creation of a “National Guard” that would integrate with the current armed forces’ reserve and retired military personnel. The National Guard would specialize in civil support functions but, when necessary, would augment the warfighting capabilities of the armed forces.[29]

With regard to countering propaganda and disinformation, Admiral Mednikarov envisioned a national level organization that would cooperate with relevant ministries, including the Ministry of Defense.

Reasons for Caution

A quarter of the respondents questioned the need to expand further the spectrum of tasks assigned to the military in their third role. They admitted that the armed forces could be called upon to contribute to emergency or crisis management at home, but only in isolated cases when the capacity of the Ministry of the Interior was overwhelmed. The arguments for this viewpoint came from two main strands of thought: the effectiveness of the military contribution and the pitfalls such contributions could involve. There is also a third reason—the potentially negative influence on the warfighting capacity of the military—that will be addressed in the next section of this article.

Even respondents that supported the expanded role of the military emphasized the need for better integration and cooperation, regular combined training and exercises, new training programs at the military academies that bring together military personnel and representatives of civilian organizations contributing to crisis management. One expert felt that the spectrum of internal tasks had expanded too quickly in recent years. Before considering new tasks, one needs to make sure that the tasks currently assigned are sufficiently financed, and the respective capabilities are developed comprehensively. Another expert stated that no new tasks are needed; it is better instead to invest in training and enhancing the resilience of the public administration, the economy, and society. A third respondent confirmed the need to invest more in combined training, as well as in providing a common situational awareness of both civilian authorities and the military participating in crisis management operations, which may be particularly challenging in an urban environment.

Amb. Valeri Ratchev, retired Colonel and former Deputy Commandant of the “G.S. Rakovski” National Defense College and Chief of Cabinet of the defense minister, in a way summarized these arguments stating that a formal mechanism for coordination is badly needed. This mechanism should provide for both operational coordination and national-level collaboration in the development of crisis management capabilities.

The second type of argument was best expressed by Col. (ret.) Vladimir Milenski. In his opinion, the current legal framework provides sufficient flexibility, but at times flirts with dangerous areas:

At home and in peacetime, the armed forces can be used strictly for logistics [including medical] tasks and eventually to provide communications. Any task, potentially involving coercion to the own population, such as “area isolation” and establishing checkpoints, is inadmissible, no matter the anticipated intensity of the use of force. … The armed forces are the national machine for lethal effects, and even the assignment of “soft coercion” contains in itself the threat to transition to a higher degree of harshness. Where is the end of this process? Moreover, where are the guarantees for non-escalation and termination of the military involvement? What will be the consequences for the image of the military and the societal trust in the armed forces?

Milenski concluded by stating that the assignment of such roles to the military could have both immediate and long-term detrimental effects on national security.

Another caveat is that the engagement of the armed forces may lead to an increased civilian dependence on the military contribution. This is already happening in Bulgaria, for example, in aerial firefighting. Yet another reason for concern is that the continuous reliance on support by the military may prevent the deployment of more efficient solutions provided by civilian agencies or commercial companies.[30]

Finding the Balance

Eight experts, or nearly 20 % of the respondents, did not directly question the idea of further expansion of the military role at home but stated instead that the boundary between ‘traditional’ and new military tasks is rather fuzzy, and a number of additional tasks have been added recently without a clear and unifying intent. They recommended conducting a comprehensive review of the legal framework, the actual status of the present capabilities that the military possesses for performing its third role, and the effectiveness and efficiency of the military contribution so far.

One respondent underlined that such a review should be conducted in an inter-agency format, using a set of politically approved planning scenarios. The review would be expected to lead to a prioritized list of requirements and a reconsideration of the tasks assigned to the military. Several respondents emphasized again the need to establish clear inter-agency procedures, an enhancement of the combined training of civilian agencies and the military, and investment in the “strategic culture” of collaboration.

Three respondents pointed out that such a review of the domestic tasks of the armed forces should be conducted as part of an ongoing review of national security and the Strategic Defense Review. The author shares this view since the most critical part of the defense review will be to find a balance between the warfighting capabilities of the military, their involvement in deployed operations aiming to shape the security environment, and the contribution to crisis management at home, all to be carried out under harsh demographic and financial constraints.

Options for the Future and Decision-making Context

In the final phase of the defense review, Bulgaria’s state leadership faces a choice: to confirm existing tasks, including those assigned to the military in March 2020, and to expand them further, or to prioritize those tasks, building on existing capabilities to provide effective and efficient support in a crisis. The involvement of the military in managing the Covid-19 pandemic and the emergency situation in Bulgaria has contributed to building public trust and societal respect for the armed forces. In the forthcoming election period, some politicians and political parties may be tempted to build on that trust and call for the extension of the law enforcement role of the military beyond the Covid-19 emergency, adding new tasks and/or increasing the capacity and the readiness of military units to support civilian authorities and the population on a regular basis.

As witnessed by the study presented here, the expert opinion is almost equally split, with a slight preference for performing a broad spectrum of tasks. Any further discussion in that regard, therefore, needs to be placed in a proper context. Illuminating in this regard is the conclusion of the 2019 Annual Report that the status of defense capabilities allows for the performance of constitutionally assigned roles and the tasks outlined within NATO’s collective defense and the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union, but with “limitations on time and scope.” [31] There are three main reasons for this conclusion.

First, the Bulgarian military continues to rely exclusively on combat platforms from the Soviet era. The year 2019 brought a breakthrough with the signed (and fully paid) contract to acquire eight F-16s Block 70. However, projects to acquire armored vehicles for thee battalion battle groups, two frigates, 3D radars, and others, which have been in preparation for years, are currently on hold. These projects are essential for providing interoperability with allied forces and commensurate contributions to both national defense and deployed NATO and coalition operations.

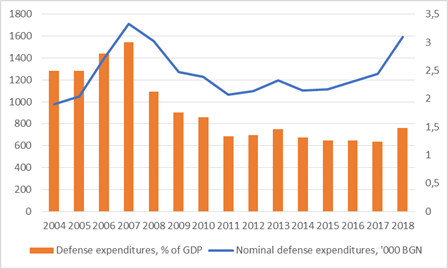

Second, as a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis, the defense budget suffered a disproportionate cut of over 37 % (see Figure 2).[32] The reduction in real terms continued until 2017 when the Council of Ministers adopted a “National plan to increase the defense expenditures to 2 % of the GDP by 2024.” In practice, the first substantial increase was in 2019 and covered the procurement of the F-16s. It is not clear at this point how the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic will impact on the defense budget. However, several opposition politicians have already called for its reduction, and one party, represented in parliament, officially proposed a moratorium on all rearmament projects and the suspension of the F-16 contract. Any reduction of the budget, or even delays in the implementation of the plan for its increase, will slow down rearmament and divert precious resources to maintaining old platforms which, in addition, are not interoperable with those of allies and hinder the armed forces’ contribution to NATO and EU operations and initiatives.

Third, and most important, is that for years the ministry of defense has been unable to meet the authorized personnel strength of the armed forces of 37,000. The current leadership has invested significant political capital in making the military service more attractive, e.g., by increasing the remuneration and expanding the potential base of recruits by increasing the maximum age for

|

Figure 2: Bulgaria’s Defense Expenditures, 2004-2018.

Legend: Left vertical axis in thousands BGN and line; Right vertical axis and columns in the percentage of GDP.

starting military service. Nevertheless, so far, it has not been able to reverse the negative trend. According to the 2019 Annual Report, at the end of the year, less than 80 % of the positions are staffed. This situation is particularly worrying for the number of junior soldiers and sailors, with the shortage approaching 30 %; the Land Forces, which are expected to provide the bulk of the surge capacity in times of a crisis, are staffed at only 74 %; and the special operations forces, expected to contribute key counter-terrorism capabilities, are 27 % under strength.[33]

As a remedy, three of the respondents see the return to a mix of contract and conscript service.[34] Another respondent, possibly anticipating such proposals, described this as “a funny idea that will swallow resources without generating results.” In this author’s opinion, the return of the mandatory conscript service might be beneficial when the domestic role of the armed forces is considered. Its overall impact, however, will be highly negative. It will further divert resources from the development of urgently needed defense capabilities and may have a detrimental impact on Bulgaria’s national security.

* * * * *

In the coming months, the Government is expected to announce its decisions based on the review of the system for national security and the defense review. It is beyond doubt that the deliberations in the final months of the review will be strongly influenced by the Covid-19 pandemic, the challenges faced in the process of emergency management, and the perceptions on what the military has, or might have, contributed. Policy-makers face the challenge to reflect diverse requirements and find a balanced solution—in an uncertain economic and fiscal environment—that both the society and allies find acceptable.

The analysis of documents and the opinions of experienced policy-makers, practitioners, and academics, summarized in this article, will assist the deliberations and allow decisions charting the most adequate way ahead. They may also be of benefit to policy-makers and analysts in other countries, facing similar challenges.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent official views of the PfP Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, participating organizations, or the Consortium’s editors.

Acknowledgment

Connections: The Quarterly Journal, Vol. 19, 2020 is supported by the United States government.

About the Author

Todor Tagarev is a professor at the Institute of Information and Communication Technologies of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and Head of its Centre for Security and Defense Management. An engineer by education, Prof. Tagarev combines governmental experience with sound theoretical knowledge and background in cybernetics, complexity, and security studies – a capacity effectively implemented in numerous national and international multidisciplinary studies.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4424-0201

30_WP_BG.pdf. Translation by the author. Emphasis added.

- видяно 16456 пъти

- Google Scholar

- DOI

- RTF

- EndNote XML